Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

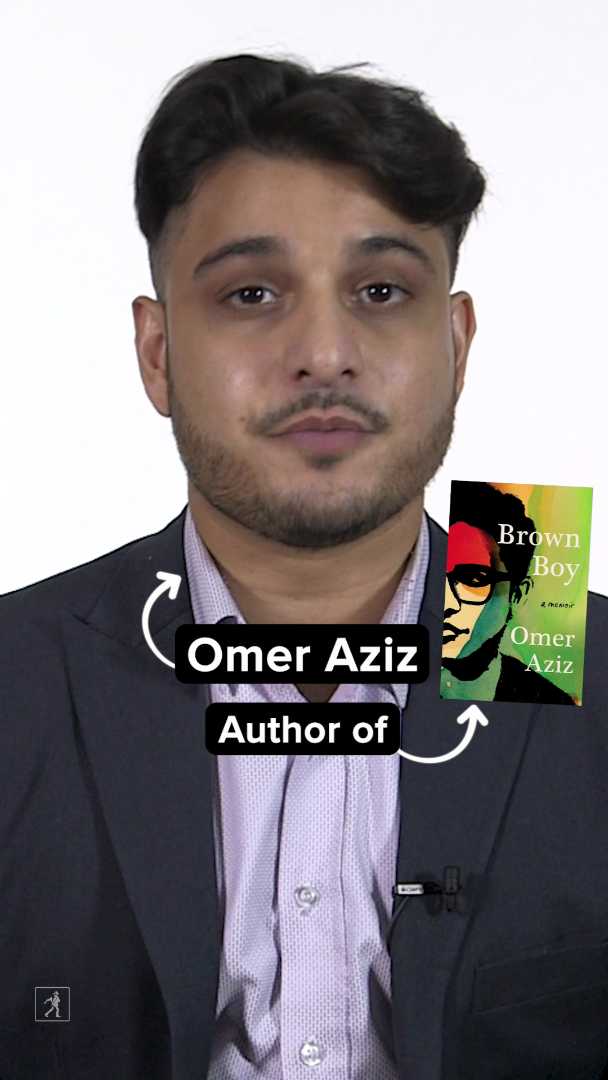

In a tough neighborhood on the outskirts of Toronto, miles away from wealthy white downtown, Omer Aziz struggles to find his place as a first-generation Pakistani Muslim boy. He fears the violence and despair of the world around him, and sees a dangerous path ahead, succumbing to aimlessness, apathy, and rage.

In his senior year of high school, Omer quickly begins to realize that education can open up the wider world. But as he falls in love with books, and makes his way to Queen’s University in Ontario, Sciences Po in Paris, Cambridge University in England, and finally Yale Law School, he continually confronts his own feelings of doubt and insecurity at being an outsider, a brown-skinned boy in an elite white world. He is searching for community and identity, asking questions of himself and those he encounters, and soon finds himself in difficult situations—whether in the suburbs of Paris or at the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Yet the more books Omer reads and the more he moves through elite worlds, his feelings of shame and powerlessness only grow stronger, and clear answers recede further away.

Weaving together his powerful personal narrative with the books and friendships that move him, Aziz wrestles with the contradiction of feeling like an Other and his desire to belong to a Western world that never quite accepts him. He poses the questions he couldn’t have asked in his youth: Was assimilation ever really an option? Could one transcend the perils of race and class? And could we—the collective West—ever honestly confront the darker secrets that, as Aziz discovers, still linger from the past?

In Brown Boy, Omer Aziz has written an eye-opening book that eloquently describes the complex process of creating an identity that fuses where he’s from, what people see in him, and who he knows himself to be.

Excerpt

Once upon a time in the colder days of my childhood, right before the new millennium, I found myself in our family bungalow watching the snow fall and dreaming of running away. Though the temperatures outside had dropped below freezing, and a snowy dust drifted over the sidewalks and cars, it felt like the world around me was on fire.

I was nine years old and waiting with terror because my father would soon be home and would ask to see my report card. Grades were important to him, even though neither of my parents had academic degrees. My father’s temper was volcanic and could explode at any moment, so the house was often tense. I usually retreated into my daydreaming and imagination when things got too loud. The outside world dazzled me with its mysteries. Had any of the neighbors seen me seeing them, they would have spotted a roundheaded boy with big eyes, a buzz cut, and a Power Rangers shirt on, observing the world through his window.

Fog formed on the glass where I exhaled. I wrote my name out in Urdu the way my grandmother had taught me, three letters, the name of the second caliph to succeed the Prophet Muhammad. Some of the houses under the white snow had lights flickering to mark the holiday, the birth of Christ, but our home was darkened. It should have been a happy time, but Christmas was always the loneliest evening of the year.

I imagined myself opening the window and running away to some magical place, an adventure beyond the confines of this house. I wondered if I could fly through the heavens like the Prophet Muhammad, on a winged horse. Staring out at the blizzard, I wondered what lay beyond this neighborhood. I was a curious, imaginative child, but beneath this wonder, I was also deeply afraid. After my father came home, at any moment there could be a verbal brawl. And I knew that when he got home, he would find out I had done poorly at school, and a beating was inevitable.

Our home was in Scarborough, a suburb on the easternmost edge of Toronto. When my father, whom I called Dada because I could not pronounce “Dad,” read his Toronto Star, he noted that Scarborough was always described by its gangs, its shootings, stabbings, and immigrant families. The world outside the house could be menacing, but I was more afraid of my father. Maybe this year would be different than all the others. Maybe there was hope. My ears, attuned to all the sounds around me, had heard the elders whispering about the midnight hour, that when the clock struck twelve, the world would come to an end—Armageddon, a boy at school had said. I didn’t want the world to end—but if it was going to end, this was a good year for it to happen.

I felt a tap on my shoulder, my reverie broken. I turned to see my mother ready to scold me. Amma had long black hair, warm eyes, and was wearing the customary shalwar kameez. She had been cooking, the onions making her eyes water as she wiped a tear with her dupatta.

“Have you said your prayers?” she asked in Urdu.

“Not yet,” I said.

“Go say them now. Allah doesn’t like when we are late in saying our prayers. Quickly, before your father comes home.”

Amma never referred to my father by his name. In Urdu she used the word Aap, a term of respect. When other people were around, she called him voh, which was like saying “they.” I spoke only Urdu with Amma. With my father, I spoke only English. I switched back and forth between the two languages with ease, but my thoughts were always in English.

I said goodbye to the snow and turned away from the window. My grandmother was sitting at her usual spot on the couch.

“Come fix this kambakht TV,” Dadiye said, cursing.

I went to the tiny box and gave it a shake. A VCR was underneath, which could play our Lion King cassette. The small living room had a crimson Pakistani carpet, black-and-white photographs of relatives with stern looks on their faces, calligraphy from the Qur’an on the wall. Dadiye sat regally with a blanket on her lap, her hair dyed jet-black, occupying the couch like it was a throne. Dadiye was my father’s mother, our matriarch, and had been living with us since the beginning of time. She was my favorite person in the house because she never asked me to pray and took me and my brother to McDonald’s on the weekend. Dadiye’s routine was the same: chai at ten a.m., followed by afternoon prayer, then watching Oprah and calling relatives back home, demanding to know every detail of gossip, managing the extended clan in Pakistan like an empress tending to her colonies. Amma’s relationship with Dadiye was respectful but tense, and I learned to play the women off each other, going between them like a boy diplomat whenever their silent treatments went on for days.

Dadiye liked to sit me down and tell me tales about the past. She said that when angels came down from the heavens, they took our good deeds and bad deeds and reported them back to Allah. She said that the Prophet Muhammad had received his first revelation in a cave from the Angel Jibra’eel.

“How many wings did the angel have?” I asked her.

“Six hundred,” she said.

Dadiye coughed. She had just recovered from pneumonia. “There was a time, long ago,” she said, “when our people were kings and princes. We were maharajas and ranis and shahs and kings and queens. We lived in peace with Sikhs and Hindus in India. My brother, your great-uncle—there is his portrait, with the white mustache—he was a doctor in London. He met the viceroy. We were once very respected. Did you know that long ago…”

The what? The who? If we were so great, why did the heater not work? What relevance did “back then” have to the snowstorms of Toronto on an unquiet Christmas night? I didn’t know what to make of her tales. Dadiye would begin such stories and then cut them off, as though the gaps had been deliberately left for me to fill. She had tried to convey that there had been a long life for her and the family before Toronto—a life that went back to Pakistan, and before that to British India, stories that she, and my parents, had left behind. They were myths that had mingled with memory and I never quite believed them.

I went to the room where my brother was sleeping. His name was Oz and he was one year younger than me and everything I was not: dutiful, good at school, responsible. My father said I should be more like him, and this made me care even less about school. He was so innocent that once he asked our father what a condom was on the way to the YMCA, before I pinched his legs until he squealed.

I laid out the prayer mat, raised my palms to my ears, and said, “Allahu Akbar.” I stood facing the East, facing Mecca, falling to my knees in prostration, and afterward sat on the prayer mat and upturned my palms to the ceiling. I prayed just like Amma had taught me and asked Allah to bless me and help me get good grades. I asked Allah if it was true that He was going to make the world end and whether I would be burned in the hellfire, the dreaded dozakh, that was described in a million different details that made me shudder. It was the holy month of Ramadan and Amma made Oz and me fast that month. She had said that the angels gathered every child’s prayers and took them to Allah during these thirty days. She said even the trees prostrated to God on the holiest nights. I thought I should take advantage of this opportunity.

“Dear Allah,” I whispered with firm conviction, “please make me a rapper.” I waited, then spoke again. “Dear Allah, send Santa Claus to our house this year. Make Dada forget about my report card. Don’t let them all go crazy tonight. Ameen.”

It was then that I heard the front door blow open with force. I quickly put the mat away. Dada was home.

“Omer! Osman! Outside Now!” he shouted.

It was a known rule never to delay when our father called. Dada’s face would go red, his eyes would widen, his temple veins would bulge as he exploded in anger. I looked to my younger brother Oz drooling in his sleep and thought whether to wake him up. Better to let him dream and go help our father on my own.

Dada was waiting for me by the door. He was short with broad shoulders and a handsome face, wearing a rumpled coat that had a giant “P” sign emblazoned on the front. He had on a Soviet-style winter cap that made him look like a brown Joseph Stalin. Flecks of snow clung to his mustache. I knew Dada was a parking officer who worked all winter and slapped tickets on car windshields, but at home he called himself an “officer of the law.”

Grunting, Dada went outside. I followed behind, waddling like a penguin in an oversized winter coat. The snowfall had grown thicker.

We were supposed to shovel together, but there was only one shovel and two of us, so I watched Dada work while he yelled.

“Don’t be a kamchor,” he said, meaning a work-thief. “Laziness will keep you back in this world. Here, do like this, like this.” He pushed a mound of snow away from the door. “See how I throw the snow? I use gravity to help me. I throw the snow. You have to use your brain, don’t be a dummy, use some force.”

As Dada threw the snow, he continued his exhortation. “Insurance companies… banks… politicians… none of them are your friends, remember. They only want to put the hand in the pocket. They are crooks.”

I nodded, pretending to understand. Down the street, I could hear the cargo train growling down the tracks.

“You guys,” he said, “you have the best of everything. When I was growing up in Pakistan, I had nothing. I had to feed the chickens, walk ten miles to school, take care of parents, cook for family, do my studies. You have everything. Am I right?”

It was always phrased as a question, forcing me—and my brother, when we were together—to assent. The one time I said, “No,” I was slapped. I stayed silent, exhaling white clouds of breath, curious about what the chickens in Pakistan had to do with the snows in Canada.

Dada exploded curse words like a cannon. “Matharchod! Use some force! Some power!” I couldn’t tell whether he was cursing me, himself, or his shovel.

After we finished shoveling snow, we went back inside the house together. I saw the two women, Amma and Dadiye, sitting on the sofa, drinking chai and giving each other death stares. They had a tense rivalry, a competition between daughter-in-law and mother-in-law, always on the verge of dispute.

“Tahir,” Dadiye said to my father. “Relax or your blood pressure will go up.”

“Let it go up!” he said.

“Chalo,” she said, and reverted to Punjabi. I didn’t understand Punjabi, but Dadiye had uttered something about how no one listened to her.

I saw my father fiddling with a plastic bag. He took out a little Christmas tree, a smile on his face.

“Tonight,” Dada proclaimed, “we will celebrate the Christmas.”

I hid my excitement. Christmas was usually a sad week for me because we never celebrated. At school, we sang carols and exchanged gifts and everyone was merry, but at home I had come to believe that Santa Claus did not visit people like us.

Amma frowned.

“Why do you wish to copy these traditions?” she asked him in Urdu. “It is Ramadan, you do not fast. We have our own holidays, like Eid, it is coming up. The children are learning not to care about their roots. They are becoming pukka Angrez.”

Dada retorted, “Jesus is our prophet, too. Look at how Christians built the modern world. We should learn from them.”

“Jews do not celebrate Christmas,” Amma said.

“I am Jewish,” Dada retorted. “Look at how Jewish people take care of each other, build schools, become doctors. What do we do? Only build madrassas in every town.”

“Ji,” Amma said. “Christmas is for the Christians. They celebrate… the birth of… the birth of God!”

I knew she had touched a nerve, for the greatest sin in our religion was shirk, or associating partners with the one God.

“I am Christian,” Dada said. “We must integ-rate, Salma. We must adopt these traditions! This is our country! Otherwise we will be stuck in our past.”

Dada had gone red in the face. I could feel another argument about to erupt.

Between husband and wife, grandmother now intervened. Dadiye gestured to me and, in her flair for drama, pronounced a matriarch’s firm rebuke.

“They will forget everything,” Dadiye said. “You will see. When kids are born and raised here, they forget their roots. This is the gora’s land, remember.”

Amma responded to this sacred challenge, younger woman to older. “Your children may have forgotten everything, but mine will remember.”

What were they so angry about? Why was their passion so intense? They weren’t arguing about Christmas trees or lights or Santa Claus anymore—they were fighting about so much more, about heritage and tradition, culture and religion, and how to raise me and my two brothers, Oz and Ali, the latter still a baby, in the country where we were born but that they had migrated to only recently. The past, present, and future were enmeshed in conflict.

As the screams grew louder, I covered my ears and ran toward the bathroom. I shut the door and crouched down by the toilet. Here, alone, I was safe.

Vicious words were uttered outside the door in Urdu, a poetic tongue, which made the words more poisonous.

Matharchod!

Thief!

Sinner!

Drinker!

Hellfire!

From a mud hut!

Bring the Qur’an!

A shattering silence.

If it wasn’t for my hard work, we’d still be in the projects!

I had been warned by my parents not to make friends with kids from “broken homes.” As the shouts grew feverish outside the door, I wondered if we weren’t broken, too.

Long into the night, the elders fought. They sounded merciless, as if they had been arguing this way not for ten years but a hundred years. They were carrying wounds I could not fathom, stories I had not yet discovered. Past lives and remembrances that they held with desperation, tempers exploding because none of their pain could be put into words. I did not understand that the anguish they carried was tied to a deeper story of leaving their pasts behind, reinventing themselves in a cold and distant country. They were growing up in a new world, just like I was, unanchored souls without a secure life. Though migration could be full of beautiful journeys, there was also a bitterness at the heart of the experience. Bitterness and violence. Families were citadels of memory, connecting stories to future generations—but the chain had been broken along the way, and could be redeemed only in the children.

The shouts grew louder. The sound of thunder, a blitzkrieg of broken plates. I covered my ears. I hid. I dreamt of escape.

When the battle ended, it turned out the little Christmas tree didn’t even work.

Ten years before our nightly family duels, on another winter day, a plane landed at Toronto Pearson Airport. Among the migrants and travelers and visitors was my mother, Salma, who was leaving her family in Pakistan to join the man she had married in Canada.

She was twenty-nine, a teacher who loved her students, setting out for the new world. The bitter cold stung her face, the wind sharp as needles. But stepping onto the tarmac, the woman, whose beauty was noted by all the locals of her community, was reminded of the snowfalls in her village in Pakistan, a place called Murree, up in the mountains where the kids made snow forts and snowmen during their own winter days.

On her mind was the village left behind and the new country that was to be sacralized by the word home. The strange sounds of English would have to be learned, the tasteless food adjusted to, and the mannerisms of this frigid city deciphered. She had come to Canada only two years before I was born, rupturing the tight-knit family she had loved. Now everything was new. She was a stranger with a young family.

My father had immigrated in the 1970s and was studying at a community college while working odd jobs. His first name was Tahir, the eldest of three children born right after Pakistan became independent. A child of the city Lahore, he knew the world better than my mother. When Dada arrived in Toronto, he was part of that great movement of peoples brought on by the opening of immigration laws in Canada and the United States. Like migrants before him, Dada struggled first with his name. The white people of his new country could not pronounce Tahir, so they called him Tire. They could not pronounce his middle name, Mian, so they called him Mr. Man. Aziz was rhymed with disease, and other slurs and cusses were spoken, some replied to but most unanswered, the second looks and backhanded comments internalized into his combustible temperament. But Dada was a man who took nothing from no one and believed he was as good as any white man. Fed up with his name being slandered, he did what many immigrants before him had done and took on an entirely new name. From that day forward, Tahir was known as “Miami.”

When Dada was still a student, his father in Pakistan passed suddenly from a heart attack. The duties of manhood were passed on to him overnight, and he quit school to become the sole breadwinner for the family. He worked as a waiter, serving the powerful white men of the city as they spent more money on a single meal than Dada earned in an entire month. Next, he walked through the snow asking anyone who might listen for a job. One day, he saw an officer in a white uniform, went up to him, and asked to know what he did. A few weeks later, Dada was hired as a parking officer, and for the next fifty years he walked across Toronto, ensuring no one had parked illegally. He sent money back home so his relatives would not starve, and used his savings to bring my widowed grandmother, Dadiye, to Canada.

Whereas Dada came from the city, Amma came from the countryside. Rural and landless peasant folk lived in those mountains of Murree. The people of her village had the features of northernly warriors: tall, light brown skin, sharp green eyes. They spoke a dialect called Pahari, and families lived and raised children together, passing on their ancestral traditions.

Tensions crippled their marriage from the start; Dada expected a quiet Muslim wife, but Amma saw herself as his equal, fierce in her own right, and wishing to preserve her heritage. She was not the docile, reserved woman she seemed to be, and this led to quarrels between my mother and father and my mother and grandmother.

It was a strange union: the wife being religious, the husband being secular; the wife resisting the pull of assimilation, the husband rushing to assimilate and discard his prior identity. Theirs was not what some modern types in the community now call “a love marriage”; it was arranged, pure and simple. Marriage was considered too grave and serious a matter to be left to the whims of children. The contract between past and future was to be preserved by the elders, passed on for posterity, made sacred in the union of marriage.

When I was three, Amma took me and my brother to Pakistan. We met our cousins and relatives, but I remembered nothing from the trip. She told me that her village was part of my roots, and in our home she was fiercely protective of her family’s origins—especially when my father belittled them and said she came from “a mud hut.”

As I grew up in the chaos of a household constantly at war with itself, I learned to be hypervigilant of my surroundings. Omens and warnings were around me. Evil eyes above me. Shame, sharam, within me. Six of us were crammed into our small household: along with my father, mother, and grandmother there were my two younger brothers, Osman and Ali—Oz one year younger, and Ali just two. Coincidentally, the three of us were named after the caliphs who had succeeded the Prophet, men we were taught to revere, but whose real stories were deeply tragic. Three generations stuffed together in a forgotten corner of Canada, with cockroaches in the kitchen, a beat-up Pontiac in the driveway, and an oldest son about to come of age in the new millennium.

Over sleepless nights, I lay in the bedroom and stared up at the cold darkness, watching the moon shining past the trees, feeling alone and terrified. As the snow fell faintly, I closed my eyes and imagined another world, one beyond the highways and fields, waiting for me, if only I could reach it. If only I could escape this northern winter.

Reading Group Guide

Get a FREE ebook by joining our mailing list today! Plus, receive recommendations for your next Book Club read.

Introduction

Brown Boy is an uncompromising interrogation of identity, family, religion, race, and class, told through Omer Aziz’s incisive and luminous prose.

In a tough neighborhood on the outskirts of Toronto, miles away from wealthy white downtown, Omer Aziz struggles to find his place as a first-generation Pakistani Muslim boy. He fears the violence and despair of the world around him and sees a dangerous path ahead, succumbing to aimlessness, apathy, and rage.

Weaving together his powerful personal narrative with the books and friendships that move him, Aziz wrestles with the contradiction of feeling like an Other and his desire to belong to a Western world that never quite accepts him. He poses the questions he couldn’t have asked in his youth: Was assimilation ever really an option? Could one transcend the perils of race and class? And could we—the collective West—ever honestly confront the darker secrets that, as Aziz discovers, still linger from the past?

In Brown Boy, Omer Aziz has written a book that eloquently describes the complex process of creating an identity that fuses where he’s from, what people see in him, and who he knows himself to be.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. Think back to the opening of this memoir. Why do we start in an interrogation room in Israel rather than Canada or America or somewhere else? What is the significance of beginning here, and how does this scene echo throughout Omer’s coming-of-age story?

2. The first scene establishes how one can be an outsider with others despite similar race, ethnicity, or culture. How does the author establish this feeling to echo with the rest of the book and how does he find ways to navigate his identity, religious upbringing, and professional life?

3. How does family, cultural, and generational differences come into play in this work?

4. How does privilege play a role in this memoir? For example, how does Omer’s experience growing up in a Canadian working-class town differ from his time in a French low-income immigrant town for example?

5. In Paris, Omer faces an existential crisis, depression, and shame over his life and the expectations of his family. How has his past affected his future? What are ways families can help their children succeed while encouraging mental health and growth?

6. Describe Omer’s return to Canada from England. How is he treated differently? Think back to a time when you made your own path in life and returned to your hometown. How were you treated differently or the same? What changes did you see in yourself, in others, in your environment?

7. What does the title Brown Boy mean to you after reading the memoir?

8. How does history play a significant role in this book?

9. How do we view the ending on Omer’s journey to Pakistan? What did you learn from it?

10. How has Omer changed over the course of the memoir? What did you take away from the book?

11. Consider Omer’s love of books as a transformative experience. What books have changed your life?

12. How play does class differ in America, England, and France through the author’s perspective? How are these places similar but distinct and how does the author navigate these places?

13. The title Brown Boy was inspired by Richard Wright's Black Boy. After reading this memoir, read Richard Wright’s classical text and note how Omer and Richard are having the same conversation or where they differ.

14. In Brown Boy, Omer says this about memory: “Memory was testimony, a record of partial truths, a reclamation of personal history. Memory was imperfect, but it was a record that could be preserved, a way of seeing” (page 293). How have your memories played to you and your family’s truths and history? How have they shaped who you are today and who you were before?

Why We Love It

“In luminous and honest prose, Omer Aziz’s memoir delves into his childhood as the son of Pakistani immigrants in Canada, rising through elite educational institutions and organizations, inspired by the charisma of Barack Obama. Through his ascent, Aziz questions if assimilation is truly the only option, and if so, what is its cost? In this compelling memoir, I was reminded of the wisdom found in Saeed Jones How We Fight for Our Lives, and the beautiful and powerful commentary in Sarah Smarsh’s Heartland. Equal parts of engaging prose and good humor, Brown Boy is a memoir that will stay with you long after the page, addressing questions on race, class, and culture.”

—Kathy B., VP, Editorial Director, on Brown Boy

Product Details

- Publisher: Scribner (April 4, 2023)

- Length: 320 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982136314

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"A sterling portrait of personal revelation, cuts to the bone." -- Publisher's Weekly (starred review)

"The significance of Omer Aziz’s Brown Boy is captured in the very first story he tells--that tension between being caught between two worlds. When Derek Walcott writes, 'Where shall I turn, divided to the vein?,' Aziz responds with Brown Boy, a powerful articulation of what it means to navigate not just identities, but borders and possibility." --Reginald Dwayne Betts, author of Felon

"A brilliant and moving memoir of, among other things, class migration and the choices made by outsiders. Aziz writes with sensitivity and honesty about the tensions between growing up in a working class immigrant home and the worlds of elite education and politics. This book will surely make it onto any reading list exploring the twin preoccupations of our time: race and class." -- Zia Haider Rahman, author of In The Light of What We Know

"Omer Aziz’s astonishing journey from economic hardship and violence to Yale and becoming a foreign policy advisor would be fascinating even if it didn’t tell us things we absolutely need to know: Why have the white and minority communities withdrawn into their separate corners; what can be done to bring them together? An essential memoir." -- Akhil Sharma, author of Family Life and An Obedient Father.

“This breathtaking, brilliant memoir had me from page one—I couldn’t put it down. Omer Aziz is a poet, his writing luminous. Brown Boy is eye-opening, achingly honest, alternately hilarious and heartbreaking—an unforgettable book.” —Amy Chua, author of Political Tribes and Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother

"Brown Boy is a poignant, unflinching exploration of cultural identity: the roles we perform, the ways we are misperceived, and the conflicted feelings we can have about our pasts. Omer Aziz illuminates what it is like to be the child of immigrants and the unique invisibility that comes with being South Asian. I saw myself reflected in these pages. How rare, to encounter one’s story with such candor and vulnerability. How rare, and how necessary."

—Maya Shanbhag Lang, author of What We Carry, a New York Times Editors’ Choice

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Brown Boy Hardcover 9781982136314

- Author Photo (jpg): Omer Aziz Photograph by Amr Jayousi(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit