Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

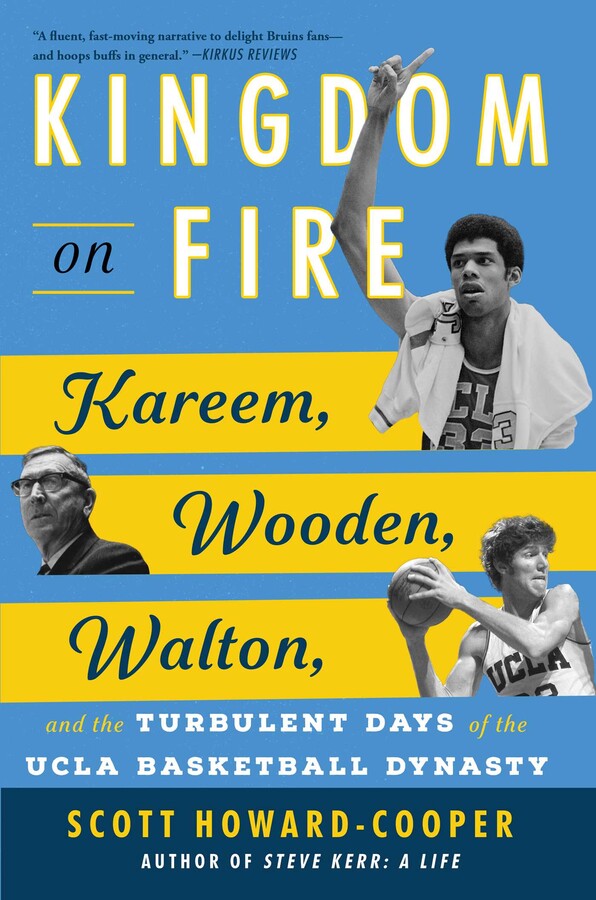

Kingdom on Fire

Kareem, Wooden, Walton, and the Turbulent Days of the UCLA Basketball Dynasty

Table of Contents

About The Book

Few basketball dynasties have reigned supreme like the UCLA Bruins did over college basketball from 1965–1975 (seven consecutive titles, three perfect records, an eighty-eight-game winning streak that remains unmatched). At the center of this legendary franchise were the now-iconic players Kareem Abdul Jabbar and Bill Walton, naturally reserved personalities who became outspoken giants when it came to race and the Vietnam War. These generational talents were led by John Wooden, a conservative counterweight to his star players whose leadership skills would transcend the game after his retirement. But before the three of them became history, they would have to make it—together.

Los Angeles native and longtime sportswriter for the Los Angeles Times, Scott Howard Cooper draws on more than a hundred interviews and extensive access to many of the principal figures, including Wooden’s family to deliver a rich narrative that reveals the turmoil at the heart of this storied college basketball program. Making the eye-opening connections between UCLA and the Nixon administration, Ronald Reagan, Muhammad Ali, and others, Kingdom on Fire puts the UCLA basketball team’s political involvement and influence in full relief for the first time. The story of UCLA basketball is an incredible slice of American history that reveals what it truly takes to achieve and sustain greatness while standing up for what you believe in.

Excerpt

1 ON THE EVE OF DESTRUCTION

The center of attention in a crowded room, prodding strangers, no hope of blending among fellow students for emotional refuge—he hated these moments even while mature enough at eighteen years old to handle them. Lew Alcindor was then, as he would always be, an ideal teammate in part because he preferred to deflect the spotlight, the antithesis to his dominating presence on the court. The real joys were as in early 1963, as a high school sophomore at Power Memorial Academy in New York City when fellow Panthers staged a 7-Foot Party in the privacy of the locker room. He stood shoeless and backed against a pole, a teammate stepped on a chair and placed a ruler at the top of his head to draw a line, another unfurled a tape measure, and yes: seven feet tall. Lewie, as they called him, broke into a big smile and laughed along as the others jostled him in celebration before a player unveiled a doughnut-like pastry filled with jelly and topped by a candle to mark the occasion.

On May 4, 1965, though, senior Alcindor was alone among many. He stepped from the Power cafeteria into the gym at 12:33 p.m., wearing the school uniform of white dress shirt, dark blue slacks and jacket, and dark thin tie as several hundred sportswriters, photographers, TV crews, and radio broadcasters lined the room. Amid the snaking cables and equipment of the radio and TV men in the age of rapidly expanding electronics, appearing poised and articulate beyond his years, he confronted the microphone.

“I have an announcement to make,” Alcindor said with some reporters underfoot and thrusting recording devices to catch the droplets of words. “This fall I’ll be attending UCLA in Los Angeles.”

Alarms sounded on wire-service teletype machines in newsrooms out to the West Coast, the ding-ding-ding of a bicycle bell alerted an arriving bulletin ahead of the black-and-white TV images to be beamed across the country. This was historic. Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor Jr. was seven feet, three-quarters of an inch, had scored more points and grabbed more rebounds than any high schooler in a city with a celebrated basketball tradition, and had led Power, an all-boys Catholic school on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, to 71 consecutive victories. Not only that, UCLA coach John Wooden quickly noted, the recruit was “refreshingly modest and unaffected by the fame and adulation that have come his way, and he plays extremely well at both ends of the floor. His physical size is as much a part of his ability as his team play, hustle, and desire.” The press conference had confirmed as much. Alcindor would rather have been anywhere else, yet handled the announcement with the ease of an experienced politician.

Speaking publicly at all was a big deal after the years Alcindor was gladly shielded by his Power coach, Jack Donohue, from the media and the sixty or so colleges that charged to recruit him. The family got an unlisted telephone number and hid behind the curtain. Even they did not want to step out of line. “Can’t talk anymore, Mr. Donohue said not to say anything,” Cora Alcindor said that morning, just before her son’s lunch-hour announcement.

When it finally came time to break the silence, when Alcindor entered the gym in the formal Catholic school uniform to change the course of college basketball forever, he was even allowed to take questions. The decision came later in the academic year than originally anticipated, he responded to one query, because he was “very confused” about whether to stay close to home. It must have been news to Wooden, who believed Alcindor had committed to UCLA about a month before, at the end of the recruiting visit to Los Angeles. He expects to focus on liberal arts in college. He chose UCLA “because it has the atmosphere I wanted and because the people out there were very nice to me.” No, he replied to another, apparently serious question, there are no liabilities to being tall in basketball.

In Los Angeles, UCLA athletic director J. D. Morgan, holding back his glee, pronounced the university “tremendously pleased” and added, “Of course, this is the boy’s announcement. By the rules of our conference we are not permitted to announce such enrollments.” The hype machine cranked up coast to coast, from the pulsing media market of the East to the publicity center in the West. “His high school press clippings make Wilt Chamberlain and Bill Russell look like YMCA athletes,” John Hall wrote the next day in the Los Angeles Times. “His final decision was awaited with more mystery and fanfare than the word on the first trip to the moon. The pressure on him here will be tremendous.”

Except pressure was nothing new, and a white columnist in his late thirties and twenty-five hundred miles away knew nothing about the scrutiny Alcindor had been living under. It wasn’t grand UCLA, with national championships in 1964 and ’65, the latter only six weeks before his announcement, but New York basketball had its own challenges. The longer the Power win streak went, the more the school and its star center became a target for opposing teams, for media, and for the public. The spotlight went from bright to searing to loathsome as sportswriters made victory a foregone conclusion and Alcindor lost the joy of playing before he left high school. He was eighteen and already burdened by success.

Plus, the racism. Alcindor entered Power the same year the Freedom Riders began in the Deep South and he followed developments as protesters, white and black, put themselves at risk to desegregate interstate buses. When his parents sent fifteen-year-old Lew to North Carolina on a Greyhound in April 1962 to attend the high school graduation of the daughter of a family friend, his body wedged into an aisle seat for the six-hundred-mile ride, Alcindor saw for himself: the WHITES ONLY signs of the Jim Crow era around restaurants, drinking fountains, and restrooms as the Greyhound reached Virginia and rolled farther south. Even the businesses he saw along the way. Johnson’s White Grocery Store. Corley’s White Luncheonette. Scared and conspicuous—tall, even for an adult, and black—he felt the need to ask local blacks, “Are you allowed to walk on the same side of the street as white people?”

It felt like being in a different country. Alcindor read about lynchings from his parents’ subscription to Jet magazine. The anger from hearing about four girls, none older than fourteen, being killed in a bomb blast while attending a Bible class in a church in Birmingham, what the FBI later said was an act of the Ku Klux Klan, boiled inside him for months. His stomach clenched in fear as he waded into the dangerous world and pushed Alcindor to wonder if he would be hacked to death during the ride. He couldn’t help but think of Emmett Till, murdered at fourteen while visiting Mississippi.

His own coach at Power, the same Jack Donohue who portrayed himself as Alcindor’s protector, left Lew emotionally scorched as a junior in early 1964 with a halftime rant. As Power led a weak opponent by only 6 points with a 46-game winning streak on the line, a frustrated Donohue pointed at his star and shouted about not hustling, not moving, not doing any of the things Alcindor is supposed to be doing, how “You’re acting just like a nigger!” Donohue initially spun the furnace blast of racism into good coaching, telling Alcindor after the victory it had been a motivational ploy, and a successful one at that, and down the line would say Lew misunderstood or deny making the comment at all.

Alcindor began to find his public voice when he joined the newspaper for the Harlem Youth Action Project in 1964. He covered a Martin Luther King Jr. press conference when the preacher came to New York, listening intently while standing in the third row of people behind King. That same year, seventeen-year-old Alcindor worked a fourth consecutive summer at Friendship Farm, a camp run by Donohue in upstate New York, teaching basketball to eleven- and twelve-year-olds out of obligation to his coach while mostly wishing he were somewhere else. In the months before his senior season of high school, Alcindor again planned to drop the job to focus on work that inspired him, as sports editor of the newspaper for a New York youth organization, only to be guilted into another trip to Friendship Farm when Donohue admitted using Lew’s name to attract customers. Absentmindedly doodling in the dirt with a stick one day, his mind adrift with a world spinning wildly out of control, Alcindor looked down to see what he had scratched in the earth: DEATH TO THE WHITE MAN.

A week after returning from Friendship Farm in July 1964, a year before his UCLA decision, riots swept eight blocks of Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant after an off-duty police officer fatally shot fifteen-year-old James Powell. The cop claimed the shooting was a reaction to being attacked by Powell with a knife, but about a dozen witnesses countered the white lieutenant had gunned down the unarmed black ninth-grader. Back in the city from the beach on a hot, muggy Sunday, Alcindor got off the subway to browse jazz records before meeting friends, stepped from 125th Street station and face-to-face with chaos. Looting, smashing windows, cops swinging nightsticks, and flying bullets overwhelmed his senses. Unsure where the shots were coming from and with few options for taking cover, Alcindor did his best to crouch behind a lamppost as people ran past. He stood in shock, frozen except for a slight trembling, until he snapped out of the trance and took off in a dash for safety, thinking only that he wanted to stay alive. Finally finding sanctuary, “I sat there huffing and puffing, absorbing what I’d seen, and I knew it was rage, black rage. The poor people of Harlem felt that it was better to get hit with a nightstick than to keep on taking the white man’s insults forever. Right then and there I knew who I was and who I had to be. I was going to be black rage personified, black power in the flesh. I was consumed and obsessed by my interest in black power, black pride, black courage.”

It struck Alcindor that being so tall made him an easy target. He wanted to throw a brick, partly for the lieutenant who shot Powell, partly for the racist approach of Donohue, and partly for white teachers at Power “who didn’t think it important to teach us about anyone with a black face.” Alcindor decided against retaliating. Instead, he went to the office of the youth group’s newspaper office and helped put out a special issue on the riot, “chronicling for history what the white media was ignoring. While they were busy tabulating the property damage and police injuries, we were tabulating the cost to the community, to individuals’ spirits, to the hope of easing racial tensions.” Interviewing residents who lived through the flashpoint, he felt their pain and related all too well to the suffering.

It took only until his senior year at Power for Alcindor, his insides churning, to become a “very bitter young man, and angry with racism.” No longer was New York a place of youthful innocence, where he started going to Madison Square Garden regularly as a seventh-grader, learning winning basketball by watching Bill Russell when the Celtics visited, admiring the way Russell played for his teammates with rebounding and passing while being a menace defending the basket. It didn’t feel insular anymore, as it had for so long in the Dyckman Street projects in Inwood, the multiethnic neighborhood at the northern peninsula of Manhattan, with the Hudson River to the west and the Harlem River to the east. Alcindor’s father, Ferdinand Sr., a stern man of six foot three and two hundred pounds known as Big Al, was a police officer with the New York Transit Authority with a musicology degree from prestigious Juilliard and handed down his passion for jazz to his son. Along with his mother, Cora, a seamstress, Alcindor’s parents made education and manners a priority. The home was filled with books and magazines and music and they decided their only child would always attend Catholic schools with the belief they were the best in the city.

The only child had the solitude of his own room in Dyckman from three years old through high school, a rarity among his friends. Yet he was a teenager thirsting for freedom from the mother he found overbearing and a distant father who would go days without talking to Lew, sometimes opening a book wide across his face to avoid eye contact with his son longing for a relationship. Arguably the greatest player in the history of the sport from high school through college and the pros would in retirement remember playing basketball with Big Al once. He wanted out.

Alcindor narrowed his college choice to Michigan, Columbia, St. John’s, and UCLA. He liked Columbia as the chance to attend school walking distance to Harlem and a subway ride to the jazz clubs he had to leave early as a high schooler to make curfew. And making it in the Ivy League would send the message of Alcindor as more than a brainless jock. But the program consistently lost and he wanted to win, not build. St. John’s had the lure of Joe Lapchick, a coach Alcindor respected professionally and liked personally—Alcindor had been friends with Lapchick’s son since eighth grade and was a frequent visitor to the Lapchick home. The school was forcing Lapchick into mandatory retirement, though, removing the biggest appeal for Alcindor. When St. John’s also attempted to hire Donohue as an assistant, likely in hopes of a Power package deal, the school, clearly unaware of Alcindor’s bond with Lapchick and broken relationship with Donohue, had deeply wounded itself for years to come.

President Lyndon Johnson, a Texan, wrote on behalf of the University of Houston and its emerging program. Holy Cross, in some coincidence, hired Donohue as head coach in April, topping the St. John’s opportunity, but Donohue’s star from Power gave only a courtesy campus visit and did not seriously consider continuing the relationship. The memory of the halftime language, coaching strategy or not, stormed back into Alcindor’s consciousness as he stood in the middle of the Harlem riot the following summer. While he would always praise Donohue for helping develop his game, Lew had no interest in more time together.

The decision came down to St. John’s, soon to hire Lou Carnesecca as head coach, or UCLA. Alcindor felt an early connection with Wooden, albeit not to the same extent as with Lapchick, and no bullets had ever whizzed past his head in California. One was in Queens, a borough east of Manhattan, close enough to imagine Cora as a constant presence in his life at a time he wanted to escape the grip of parental oversight. The other was a continent away. So, UCLA.

Los Angeles would be different. He was sure of it. Alcindor dreamed UCLA into an Eden “where I would play basketball, study, go to an occasional beer bust, stroll arm in arm on the campus with the chicks, enjoy long bull sessions in the dorm with the cats and, in general, live the collegiate life that I’d read about and been promised by all those guys I’d talked to on my first visit the April before.” Maybe it was best to get away from the prejudice of New York and what he saw as a semipermanent riot situation in Harlem, Alcindor told himself, while Southern California was a land “where people were color-blind, and a man could live his life without reference to color and race.” The campus in particular was in open-minded Los Angeles, specifically in Westwood, a moneyed area neighboring the hillside homes of swanky Bel Air and a few miles from Beverly Hills.

And it felt so familiar. Jackie Robinson, who broke the baseball color barrier with his Dodgers debut in Brooklyn the day before Alcindor was born in Harlem on April 16, 1947. Robinson played four sports at UCLA, including basketball, and became Lew’s first hero, at age six. Robinson was also a favorite of Cora Alcindor’s, who pointed out to her son how Robinson was so articulate, implying he was someone for Lew to pattern himself after. Don Barksdale, the first African American basketball Olympian for the United States, in 1948, was a Bruin. So was Willie Naulls, in the NBA from 1956 through 1966 and sometimes with teams that would practice at Power when in town to play the Knicks. (Naulls ended up with quite the side career as a recruiter. Knicks management once sent him to Boys High in Brooklyn to convince rising star Connie Hawkins to attend college in New York so the Knicks could later acquire him via the territorial draft. Red Auerbach, the coach and general manager of the Boston Celtics, similarly pushed to get Hawkins to a New England university. Both lost—Hawkins chose Iowa.)

UCLA graduate Ralph Bunche, the first colored man to win the Nobel Peace Prize, in 1950 for his work bargaining a cease-fire between Arabs and the new nation of Israel, wrote Alcindor on March 26, 1965, to promote the school’s “exceptionally fine record with regard to thorough and relaxed integration.” Robinson, Alcindor’s hero, also sent a letter extolling its virtues. Even if no one realized it, though, Alcindor had been won over long before by the strangest of recruiting pitches: Rafer Johnson, the decathlon gold medalist at the 1960 Rome Olympics, on The Ed Sullivan Show. Johnson may have been awkwardly wedged among Imogene Coca in a comedy bit, a tap dancer, and a puppet act, plus other guests, but nothing was lost on Lew as he watched an African American talk about being student body president at UCLA. That stuck with Alcindor.

In a time of few games being televised nationally, and none during the regular season, scanning newspapers for box scores allowed him to track the basketball team from across the country, taking particular note as a Power junior when the Bruins beat bigger Kansas. UCLA relied on speed and execution not height and force, an important selling point for the emerging star as a skinny high school kid who didn’t think he could survive the college muscle game despite an obvious size advantage. It was just how the Celtics played when he saw them at Madison Square Garden. A season later, with the recruiting battle peaking, Alcindor watched on TV as the No. 2–ranked Bruins beat No. 1 Michigan in Portland, Oregon, for the national title the same night twelve-year-old San Diego resident Bill Walton saw televised basketball for the first time. In Westwood, an estimated five hundred students celebrated by sitting in the middle of Wilshire Boulevard, a major thoroughfare, before returning to campus unscathed for the more traditional of victory rituals, a bonfire.

The official UCLA representatives, not the big-name alumni, first connected with Alcindor in his junior season, 1963–64. It may have been long after Alcindor rose to prominence, years since he was a headliner as a ninth-grader at the 1961 Christmas Holiday Festival upstate in Schenectady as Power lost to hometown Linton High with junior forward Pat Riley, but it was also exactly the right time. The Bruins, playing fluid and playing as a team, the approach that appealed to Alcindor, were about to win the first of their back-to-back national championships. Not only that, one of the stars was an African American from the East Coast, Philadelphia native Walt Hazzard, who wore uniform No. 42 in his own salute to Alcindor’s beloved Jackie Robinson.

That Donohue wrote to say he would be attending the Valley Forge Basketball Clinic in Philly, where Wooden would be speaking, was critical as Wooden stuck to his policy of not initiating contact with prospects. Wooden would not, he made clear in advance to UCLA officials when he first arrived, chase high school students, and especially not high school students beyond the Los Angeles area. “My family comes first,” he explained. “I would not go away to scout. I would not be away from home. I refused to do that, and I didn’t have assistants do that.” If he had to leave town often to recruit, Wooden said another time, he would quit instead. He did not break the pledge in the 1951–52 season for a senior in Oakland, Bill Russell, who chose the University of San Francisco and turned the Dons into a national power four hundred miles up the California coast from UCLA. Wooden didn’t break it a few years later for Wilt Chamberlain in Philadelphia, before Chamberlain picked Kansas. So, too, it would be for a New Yorker as next in line among teen-sensation centers with immeasurable potential, a stand that became harder to challenge once Wooden had a first title as proof his unique methods worked. Donohue would have to take the initiative. Perhaps, the note to Los Angeles suggested, he and Wooden could meet at the clinic.

Wooden already knew of Alcindor, of course. Everyone did, and not just street hustlers who tried to deliver Lew to different high schools and the college recruiters who followed a few years later with similar selfish motives. Even before Alcindor played an NCAA game, the owner of the Los Angeles NBA franchise was already aiming for the prodigy’s exit four years in the future: “That’s the year the Lakers are going to win only three games. I don’t know which three, but the Lakers are going to have the first pick in the draft. Alcindor will be the start of a new era.” Jerry West met him as a ninth-grader when the Lakers, like several NBA teams, practiced at Power during New York stops to face the Knicks twelve blocks away at Madison Square Garden. Alcindor never forgot the positive emotions from a conversation with Auerbach around the same time, how the Celtic boss “took enough interest in me to talk” to a fourteen-year-old.

San Francisco Warrior Chamberlain, already a dominant center after five pro seasons, and Alcindor developed a friendship in the summer of 1964, when Chamberlain owned Harlem nightclub Big Wilt’s Smalls Paradise, his Bentley parked in front to announce his presence. Seventeen-year-old Alcindor would watch Chamberlain team with Satch Sanders of the Celtics and retired guard Cal Ramsey in the prestigious Rucker Tournament, then sometimes join players back at Big Wilt’s for festivities known to last until 4:00 a.m. Lew would occasionally tag along as the party continued to Chamberlain’s two-bedroom apartment overlooking Central Park, where Wilt provided food, usually cold cuts, and an extensive collection of jazz records that played during card games. Chamberlain liked Alcindor and handed down custom-made clothes. Alcindor, in return, “stood in awe” of Wilt. On the night the group played hearts, the rule was simple: the loser drinks a quart of water. “Drink it or wear it.” Alcindor lost three in a row and ingested the punishment. By the fourth defeat, he was done, incapable of swallowing more. The others held him down and doused away.

The rest of his world was not nearly as fun loving for Alcindor, as Donohue’s wall of secrecy went up during Alcindor’s junior season, even though it was a year away from the most impassioned of college pursuits. Donohue heard a man say, “Hello, Lew,” one afternoon at Power and sternly responded, “You know the rule! No talking to my players. Out of the gym!” It came with complete backing from the family, with phone calls referred to Donohue, before the Alcindors switched to an unlisted number as an added precaution, and mail from colleges was forwarded unopened to Donohue. “We know what getting lots of publicity has done to other boys,” Cora said. “We think Mr. Donohue is a very capable man. We are with him one hundred percent. When any of those cuckoos call, we tell them they’ll have to speak with Mr. Donohue.” As Lapchick, the St. John’s coach and a good friend, said, “Jack Donohue has the most wanted basketball property in the nation. The boy just might win the national championship for some college. Jack could probably get a half dozen college jobs if he delivered Lew.”

That wasn’t going to happen, certainly not after Donohue’s halftime outburst the season before Alcindor signed, and UCLA had too much of a head start anyway. Seeing Rafer Johnson on Ed Sullivan, watching the Bruins play with precision and camaraderie in winning the 1965 national championship in Portland, loving the image of the California vibe, and the chance to be connected to Robinson, Bunche, and the other African Americans who flourished there put the school at the top of his list before Alcindor had even been to L.A. Wooden asked one thing, that Alcindor make that the final campus visit. Lew had no problem with the minor detail.

He left New York with snow on the ground and landed to find UCLA preening, so washed by sunshine, open grounds, and a seventy-degree afternoon that he couldn’t imagine living elsewhere. Two players, Edgar Lacey and Mike Warren, were dispatched to the airport to drive Alcindor to campus with specific instructions not to stare in amazement, a request that sounded reasonable enough until they saw a high school kid needing to duck to exit the plane. At that point, “It’s like, ‘Oh my God,’?” Warren said. But also, the freshman guard said in a debriefing soon after, “One of the nicest people I’ve ever met.” Warren kept reminding himself to not stare but couldn’t help it. He even checked out Alcindor in the reflection of the glass in display frames along the wall as they strode down a corridor. Alcindor folded himself into the front seat of Lacey’s Volkswagen, knees mashed to chest, for the drive twenty miles north to Westwood.

Being shown around campus by Lacey, a starting forward, Alcindor was quickly taken by the realization that if he had a twenty-minute walk to class, the steps would be on more fresh grass than he had ever seen outside of Central Park. It felt like students strolling in shorts were a parade of fashion models. Couldn’t he just stay, without going home to pack? Lacey, who had been a friend since they met as part of a group appearance of Parade magazine high school All-Americans on Ed Sullivan during Alcindor’s sophomore year, laughed as Alcindor rubbernecked at the ladies. Lacey also filled him in on an important detail: black guys hung together, but the whites were okay, too.

When it was time to meet Wooden, Alcindor found the coach’s small office, which was part of the temporary housing for the athletic department, Quonset huts of shiny corrugated steel with a new basketball arena under construction nearby. “We expect our boys to work hard and to do well with their schoolwork,” Wooden told him, traces of a slight Indiana twang coming through. “I know that should not be a problem for you, Lewis.” Hearing the formal, grown-up version of his name, not Lew or Lewie the way he was used to being addressed, felt good. Wooden in pressed white shirt and black tie, with a sport jacket on the corner coatrack, appeared to be a soft-spoken gentleman of the 1800s, with straight gray hair parted close to the middle, glasses, more quaint schoolhouse teacher than head of the best college basketball program in the country. He was every bit the grandfatherly sort that Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray would come to describe as “so square, he was divisible by four.”

Wooden through the years would dislike an emphasis on weight lifting for creating “heavily muscled fellows,” and Auerbach would remember Wooden’s response after being congratulated on Alcindor’s UCLA announcement: “Oh, you mean the chap from New York? Yes, we’re quite pleased to have him.” Wooden the high school coach would keep his team in the locker room after games longer than necessary in hopes girlfriends would give up and leave, saving players from the late nights out they wanted. He diagrammed his philosophies into a triangle-shaped composition of so much detail and introspection that Wooden began jotting down his Pyramid of Success in 1934 while teaching high school in South Bend, Indiana, and did not finish until 1950 at UCLA after countless revisions.

Wooden immediately struck Alcindor as an elder in the best sense of the word—respected and respectful, wise but not in a hurry to impress, attentive to the task at hand. Though ordinarily quick to find faults in others, especially strangers who needed him, and despite a hostility toward white people, Alcindor liked Wooden right away. Wooden won him over with a calm demeanor that made no attempt to hurriedly win over the best recruit in the country with a power play or attempt to look smart. The white fifty-four-year-old from Midwest farm country and the black teen from East Coast concrete shared similar personalities in a lot of ways. It probably didn’t hurt that Wooden was the opposite of Donohue and his gift of gab and brash sense of humor that could go overboard and would often point at the Power students. Wooden seemed more serious and almost rustic enough for Alcindor to imagine him driving a hay wagon. “He wanted to see UCLA with his own eyes, not get a painted picture from anyone,” Morgan, the athletic director, said. “If we ever used a soft sell, it was on Alcindor.” At the end of the visit, in the car as Wooden drove him to the airport for the return to New York, Lew—Lewis—said he had decided to attend UCLA.

Upon returning home, though, Alcindor started to agonize over the decision. He visited, and enjoyed, Michigan. He got another guilt trip from Donohue, who had taken the Holy Cross job fifty miles west of Boston and was pressuring Alcindor to visit. “You owe it to me,” the coach said. Alcindor, despite telling Wooden that UCLA would be the final visit, went to Massachusetts without any intention of choosing the school, a sentiment affirmed as he took note of the lack of colored students. And when a black student was chosen to give the campus tour, the guide barely waited for Donohue to be out of earshot before advising Alcindor, “If you come here, you’re crazy. This is the worst place for you to go to school. You won’t have any fun at all. You’ll be isolated, like I am. Man, pick someplace else!” Lew was going to anyway.

Wooden, still never having seen Alcindor play, flew to New York for a 1:00 a.m. meeting with his parents, after Big Al pulled a four-to-midnight shift. Morgan not only insisted Wooden continue to pursue Alcindor, even if it meant leaving Los Angeles, he also directed Wooden to take assistant coach Jerry Norman, a Catholic, in case the Alcindors had questions about church life around campus.

Morgan thought the process through in ways Wooden never did, despite the enormous stakes and despite Wooden’s being an experienced coach, leading Norman to conclude Wooden did not want the nation’s best prospect in many years. Wooden, Norman said, “was afraid we wouldn’t win with him and then we’d get criticized.” In a time few were aware Wooden could be overly sensitive, Norman had not forgotten coming to the office the first workday after the 1964 title and hearing Wooden say, “Worst thing to happen to us.” The coach did not want the expectations.

The strange New York trip, going across the country for what figured to be sixty or ninety minutes of conversation, was by Wooden’s count just his fourth or fifth home visit in seventeen seasons on the job. It also made UCLA the only school to be invited to the Alcindors’ apartment. But the meeting felt good, a relaxed discussion among the adults while Lew waited anxiously in another room for his parents to give their final approval. Basketball was barely mentioned before Norman and Wooden flew to Kansas City for a morning introduction to the mother of another top recruit, Lucius Allen. The whirlwind itinerary would become among the most important thirty-six hours in the history of UCLA sport, before the jet-setters returned to California late in the afternoon.

Announcing his college decision remained the last major moment in Lew’s life until graduation. The press conference in the Power cafeteria came seven days after Martin Luther King arrived at UCLA, stepped on the stage erected for the speech, and said in his evangelical tone that segregation was on its deathbed and “it’s only a matter of how expensive the segregationists will make the funeral.” Students staffed tables during the hour-long address and collected $747.98, which King said would go toward the voter-registration drive. Alcindor had covered the King press conference in New York, and now they shared at least a distant connection of putting UCLA in the headlines within a week. Awash in black pride, Lew was getting the chance to attend the school where Jackie Robinson studied, Rafer Johnson led, and King spoke.

The summer months that followed the press conference in the Power gym, his final days as a full-time New Yorker, were surrounded by what little remained of Alcindor’s youthful innocence. A prominent UCLA graduate, movie producer Mike Frankovich, arranged a job for Alcindor at Columbia Pictures in New York for $125 a week, mostly delivering interoffice memos. And rarely in recent years had he been able to be a more typical kid than when New York sportswriter Phil Pepe set up through the Mets public relations department for Alcindor to go behind the scenes and watch the Dodgers, Jackie Robinson’s former team, play the Mets at Shea Stadium in Queens. The New York World-Telegram and The Sun staffer first heard of Alcindor when a phone call tipped him off about a six-foot-eight thirteen-year-old ransacking the youth leagues. You will be interested in the grammar school game in the upcoming triple-header at Fordham, Pepe was informed, not just the main events of the high school or college contests. Over time, Pepe would become the rarest of people in Lew’s life, a reporter who could be let in, an older white man who could be a friend. Now Pepe was providing Alcindor with the rare gift of being an average teenager.

On August 26, 1965, they met for an early dinner at Pepe’s home. Alcindor was respectful and a little shy but did not seem uncomfortable and referred to his host as Mr. Pepe until being told to use Phil. When they got to Shea, Lew in the visitors’ clubhouse was any starry-eyed kid surrounded by heroes, awestruck while being introduced to Don Drysdale, Willie Davis, Maury Wills, and Sandy Koufax, the star pitcher who once received a basketball scholarship to the University of Cincinnati before turning his attention to baseball. Some Dodgers treated the visiting teenager as the celebrity, not the other way around. The Mets, with a dreadful roster in their fourth year of existence, en route to losing 112 games and finishing 47 games out of first place in the National League, were just happy to have Alcindor at the park, even if his boyhood allegiances were to the Dodgers. A local hero, sure, but also a welcome distraction.

Back in the real world, Alcindor’s dreamy vision of Los Angeles was crashing down before he could get there. On August 11, three months after the announcement to attend UCLA and the month before Alcindor would begin campus life, fifteen days before the boyish time at Shea Stadium, black motorist Marquette Frye was stopped by the California Highway Patrol for driving a 1955 Buick erratically in the Watts section. A crowd gathered on a muggy night. Authorities said he resisted arrest, resulting in Frye being clubbed with a nightstick and knocked unconscious. He said cops roughed up his mother when she arrived and tried to stop them from impounding her car. The cops countered that she jumped on another officer. The group began to throw rocks and bottles. Soon, an estimated five thousand people convened in a swath of the city that was sealed off by an estimated one hundred policemen and three hundred deputy sheriffs, with the National Guard about to be called in as pockets of violence erupted through the night. White occupants were pulled from cars by the crowd, even a cop from a police car, and a civilian was told, “This is no place for white men,” as he was being dragged out and beaten. The offensive finally halted when other police vehicles arrived.

Visiting friends in Watts with his parents and two siblings, twelve-year-old Keith Wilkes heard the loud pop of gunfire on the first day of the riots. He was close enough to the mayhem to come out of the house and see looters charging out of stores with merchandise. (The Wilkes family quickly returned to their quiet beachfront town sixty miles away.) Frye was released from police custody the next day, saw the smoke rising to the sky, heard for the first time about the death and destruction on the radio, and began to cry in horror. When TV stations sent reporters—white reporters—to cover the unrest, their cars were stoned and some attackers threatened the media against returning. Given that militants had been shooting at firefighters trying to extinguish the burning landscape, these warnings were to be believed. Somewhere in there, the police were trying to restore order, although in some cases the same police who had been known to prepare for shifts in the ghetto by shouting out, “L-S-M-F-T!”—Let’s Shoot a Mother Fucker Tonight. With Governor Pat Brown vacationing around the Mediterranean, it was left to Lieutenant Governor Glenn Anderson and the cops to tragically mishandle the response. Police declared the situation “rather well in hand” on the morning of the third day, when it was so not well in hand that violence resumed within hours of daylight. Anderson was more concerned about rumors that student protesters in Berkeley were plotting a lie-in to stop marching troops that he turned his back on Watts and flew north to meet with University of California regents.

Governor Brown learned from reading a Greek newspaper that the largest city in his state was in flames and quickly started the twenty-four-hour journey home. On final approach into Los Angeles International Airport, the French pilot reported the view looked similar to war zones he flew over in World War II. As the inner-city raged twenty miles southeast of Westwood, some twelve thousand members of the National Guard were patrolling the streets in troop carriers and barricading the Harbor Freeway to ensure the crucial driving artery that cut north-south near Watts remained open. That night, when television station KTLA aired the documentary Hell in the City of Angels, video was shown of cops in white helmets kicking suspects in the ass and poking gun barrels into other body parts and calling out, “First one drops their hands is a dead man.” By the time violence was officially extinguished on August 17, thirty-four people had died, more than one thousand were injured, and six hundred buildings were damaged amid an estimated $40 million of property destruction.

Alcindor was walking straight into another racial tinderbox, the same cauldron of fury and frustration that he’d felt, like a body blow, upon stepping out of the 125th Street subway station thirteen months and twenty-five hundred miles earlier. UCLA may have been a progressive college campus, and it may have been located in a shimmering part of town, twenty freeway miles from the despair of Watts, but nothing could mask the truth that Los Angeles would not be the escape he had imagined.

Wooden’s summer, meanwhile, was marked with uncertainty surrounding Alcindor. Wooden won the national championships in 1964 and ’65 with teams that were scrappy and small and utilized a speed game with a pressure defense to constrict opponents into mistakes that resulted in a sprint the other way for easy Bruins baskets. The coach subtly but clearly made sure before games that referees saw he had a stopwatch, a pointed reminder to be ready to call a violation when the other team failed to get the ball past half-court within ten seconds. Even if Wooden might not ever actually look at the timer after tip-off, he wanted refs thinking about it. The first group went 30-0 without a starter taller than six-five and was so athletic that Fred Slaughter attended school on a scholarship split between basketball and track, while Keith Erickson’s scholarship was shared by basketball and baseball and he would also later make the U.S. Olympic team in volleyball. “Have you ever been locked up in a casket for six days?” USC coach Forrest Twogood asked. “That’s how it feels” to face the menacing defense. The California coach Rene Herrerias labeled Erickson, the last line of protection in the 2-2-1 zone, “a six-five Bill Russell.”

With Alcindor, an actual Russell on defense, there would be no more scrappy. The new roster was made to stomp, not outrun, opponents after adding Alcindor, Allen, and forward Lynn Shackelford within ten days of each other. For reasons that never became clear, Wooden questioned whether Alcindor would follow through and show up in September for the start of classes, just as Wooden never believed the Bruins had much chance to win the recruiting battle in the first place. But the desire to not get Alcindor had become so obvious to Norman that he noted several instances during the late-night visit to the Alcindor home of Wooden saying, “If Lewis doesn’t want to come to UCLA, we will understand.” It was all but inviting Alcindor to change his mind. “He practically begged him not to come,” Norman said, “but the kid wanted to come so bad.”

To the Bruins’ top assistant coach, Wooden pursued one of the most promising prospects in basketball history only because Morgan commanded him. Wooden wouldn’t cross his boss even years later, after building much more clout, so he certainly wasn’t going to ignore Morgan’s wishes in 1965. Little did Wooden know how enthusiastic Alcindor was to get there, or anywhere beyond “the stifling shadow of my father and the emotional grip of my mother.” He was sentimental in snapping a series of pictures with a 35 mm camera on the final day around New York, wondering whether he was hedging emotional bets by keeping pieces of the hometown with him or documenting the departure to prove to himself that he’d really made it out. Beyond that, Lew was anxious enough to sprint to Los Angeles.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books (March 5, 2024)

- Length: 368 pages

- ISBN13: 9781668020494

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“Recaptures the complexities of John Wooden’s UCLA dynasty…[placing] readers back in more interesting times, before the stories they tell were sanded down or inflated or forgotten.” —Washington Post (Two great new basketball books set the mood for March Madness)

“Portraits of [Wooden, Kareem, and Walton] are developed with nuance and sensitivity.” —The Wall Street Journal

“Howard-Cooper elegantly weaves together sports, political, and cultural history, presenting a trenchant portrait of college basketball’s most successful dynasty against the backdrop of a country wracked by political upheaval. Perceptive and exciting, this is a slam dunk for college hoops fans.” —Publishers Weekly

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Kingdom on Fire Hardcover 9781668020494

- Author Photo (jpg): Scott Howard-Cooper No Credit(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit