Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

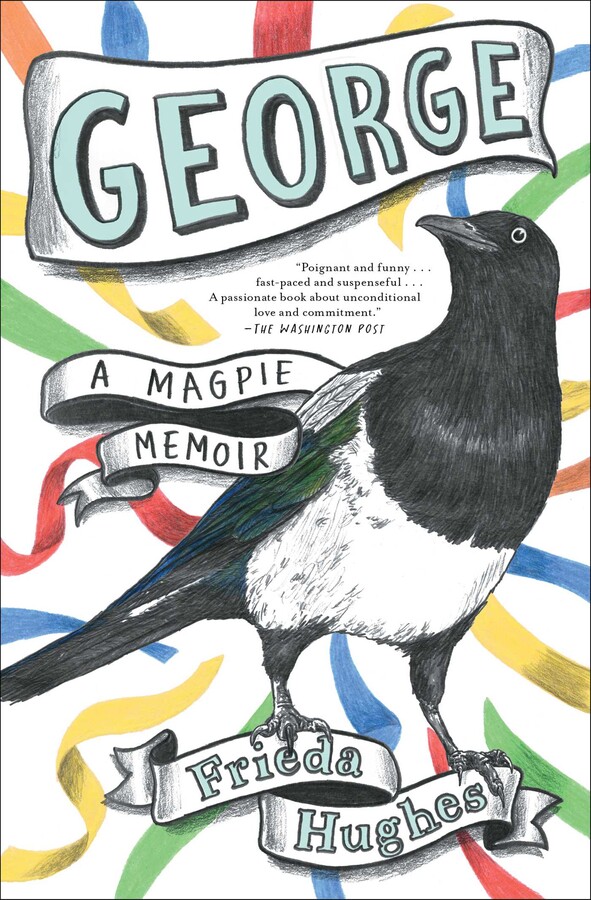

About The Book

From poet and painter Frieda Hughes, an intimate, charming, and humorous memoir recounting her experience rescuing and raising an abandoned baby magpie in the Welsh countryside.

When Frieda Hughes moved to a ramshackle estate in the wilds of Wales, she was expecting to take on a few projects: planting a garden, painting, writing her poetry column for The Times (London), and possibly even breathing new life into her ailing marriage. But instead, she found herself rescuing a baby magpie, the sole survivor of a nest destroyed in a storm—and embarking on an obsession that would change the course of her life.

As the magpie, George, grows from a shrieking scrap of feathers and bones into an intelligent, unruly companion, Frieda finds herself captivated—and apprehensive of what will happen when the time comes to finally set him free.

With irresistible humor and heart, Frieda invites us along on her unlikely journey toward joy and connection in the wake of sadness and loss; a journey that began with saving a tiny wild creature and ended with her being saved in return.

Excerpt

Working in the garden daily, I noticed a pair of magpies building a huge nest in the neighbour’s copper-leafed prunus tree, which rose out of the hedge between our two gardens about 50 yards from the front of my house.

Twig by twisty twig, they knitted this wooden bag for their babies; it hung in the highest of the branches like a dark lantern, a testament to their skill at construction, a very large, twiggy nest, shaped like a tall, inverted pear, with a twiggy lid that was attached by a spine at the back, but sat above the rim to allow parental access from the sides while protecting from the worst of the rain. I’d never seen anything quite like it.

The tree’s heavy presence and purple-dark leaves were now made more threatening by the habitation of these magpies and their staccato laughter; their noise sounded as if hard wooden blocks were being thrown at a wall, so they clattered to the ground. Toiling beneath them as I dug narrow trenches for flowerbed edging pavers, and planting hellebores and miniature azaleas, I had the idea that they were the jokers and we humans were their fools.

They screeched and made strange chugging noises; king and queen of the garden, they challenged the wood pigeons and doves and teased the jackdaws and crows without shame. They skipped and flounced and appeared hideously happy as they performed their quick little dance steps, wearing their black-and-white shiny suits with that tinge of oil-slick blue-green like a stain on their inky feathers. Where crows possessed gravitas, jackdaws possessed curiosity, and magpies possessed a tangible sense of humour.

Magpies are vermin, I was told by farmers and friends alike, and anyone who cared to voice an opinion, as if they knew all about magpies. Their seemingly universal verdict sounded trite and rehearsed rather than being a warranted judgement that any one of them had come up with on their own. So, I disagreed with them, but nevertheless, when the twelve wild duck eggs started to vanish from the nest on the island in the middle of the large fishpond I’d constructed, I began to regard the magpie nest with some suspicion.

Every morning I’d find another egg missing, and broken bits of shell littering the pond edge. It seemed the egg-eater was coming for an egg a day. Three eggs into the carnage, the duck stopped sitting and deserted the nest; the eggs continued to disappear until there were none left. It was magpies, someone told me, although in truth it could have been any number of creatures: crows, ravens, ferrets, mink, foxes, rats. Even lovable hedgehogs crave a raw egg and there are several of them in my garden. Jackdaws eat eggs too; sometimes I’d look out of the kitchen window and there would be eight or a dozen of them perched on the table and benches that stood on the bit of grass I called “the front lawn.” (I’ve since turned it into a rockery and series of winding flowerbeds full of low-growing evergreen bushes.)

The jackdaws and crows hung around the front yard like mourners waiting for the funeral in their sooty blacks, but I liked them; they had dignity and poise, unlike the magpies who were imps. If I put bread out for the birds, the big black crows would fly over, their slow, powerful wingbeats bringing them down like burnt-out space junk until they littered the crumbling tarmac of the circular forecourt, where they got on with the business of devouring bread. The jackdaws would step aside for their larger cousins. But the magpies would sidle in, cackling and fizzing, hyper-energetic and focused on food.

The bread had to be brown; I was amused to find that the birds ignored white bread altogether, which festered outside, becoming soggy heaps in the first rain and eventually washing away as a sort of greying, diluting slime. Even the rats and mice weren’t interested.

The night before, there had been fierce winds. Inside the house the windows had felt to be shaking free of their box frames, their weights rattling inside their hidden sash-coffins. The large house, beaten by the storm, gave me a sense of being in a ship on a wild sea. Our bedroom on the third floor at the back was like the bridge; looking out over the neighbours and forging a path through the stormy skies. The slimmer trees had leaned and bowed, the bigger ones had lost branches, and now here, when I looked up, was the broken, torn-apart tatter of the magpie twig-nest.

Good, I thought firmly, no more magpie nest meant no more magpie eggs, so fewer magpies to eat duck eggs. Even as the thoughts crossed my mind, I felt a stab of guilt; I’d damned them without evidence, and I’ve spent so much of my life rescuing wounded birds and animals (a compulsion begun in childhood, which eventually grew to include friends, boyfriends, and derelict houses), trying to patch them up and keep them alive until they mended, that being glad of the destruction of the nest, and the eggs that could have been inside it, was alien to me.

There was no sign of the magpie pair. They had simply vanished.

In the raised rockery beds that I’d built adjacent to the tree, a small feathered scrap caught my eye. I parted the foliage around it and found an injured baby magpie; it was almost the size of my palm—too young to walk or fly, and with only the most rudimentary feathers. Its stumpy wings were like a bundle of fan-sticks still awaiting fluff. So, the magpie eggs had already hatched. Immediately, I wanted to save it.

Although I’ve picked up various injured birds over the years, I’ve only ever seen baby birds when they’ve fallen out of the nest, already dead. This little thing was just about alive and in desperate need of care.

The baby magpie’s open beak was full of fly eggs, which didn’t bode well for the bird. I gently flushed the eggs out under a dribble from the outdoor tap; the bird was bleeding in patches all over its body, and I guessed the neighbour’s cat must have had a go at it—it looked torn in places, like a bloodied rag. I took it indoors and gave it a lukewarm bath to flush out the fly eggs from the wounds on the rest of its body; I had to use a tiny watercolour paintbrush to get the fly eggs out of its nostrils. I didn’t know what else to do, but I remembered clearly how quickly fly eggs can turn into maggots, and the idea of any egg hatching, eating flesh as a maggot before becoming a chrysalis from which would emerge a fly, made gigantic by the minuteness of its tiny, flesh surroundings, revolted me. I made sure I fished out every single one.

When I was a small child my father, who was a fanatical fisherman, forgot that he’d left a tin of maggots on the dashboard of his old black Morris Traveller. In the summer heat they turned into flies in record time, exploding the top of the old tobacco tin he’d put them in as the bulk of their bodies swelled up like miniature Hulks, clouding the interior of the car with tiny black shiny pissed-off engine-driven lunatics. When he opened the car door my father was engulfed in a cloud of quickly dispersing fizzing black dots, and I was engulfed in peals of laughter, tempered only by a sense of revulsion at the seething mass.

The magpie chick didn’t fight or struggle; on the contrary, it put up with my ministrations with the air of a creature that no longer cares. I dried it off, and got it to eat a small worm, which I dangled into its open upturned beak and dropped to the back of its throat, so it swallowed. Then I wrapped it up warmly in a T-shirt and put it in a small cardboard box. I left it to recover and hoped it might, although given its condition I had my doubts. If it lived, I’d call it George.

The sun was blazing down; it was a hot day and I didn’t want to miss the weather for planting, so I got back outside as soon as I thought George was settled and there was nothing more that I could do for him; his little head was sunken on his tiny chest and he appeared to be sleeping.

I was planting miniature azaleas beneath a couple of tall silver birches at the bottom of the garden, far away from the spot where I’d found the magpie chick, when I heard a single desperate cry. It wasn’t plaintive at all, but demanding and outraged. I searched the bushes and leaves at my feet and found a second baby magpie. It was cold and dead. Puzzled, since it couldn’t have been the source of the noise, I buried it beneath one of the cupressus trees I’d planted, and searched again, for the source of the bird call.

Thinking that it might have been my imagination—or a sound from something on the other side of the hedge, out on the road—I got on with shovelling earth, wondering how many weeks it would be necessary to find worms for the baby bird before it could feed itself. I made my way back down to the bottom of the garden where I started filling a jar with the worms I dug up. It didn’t occur to me to look up worm suppliers on the internet, because my internet connection in those days was so slow that I could barely send an email, let alone access useful information. So, I’d ask someone who knew, or I’d wait to find out, and until then, I’d dig worms.

I was turning over spadeful after spadeful of the dried leaves and woodchips that covered the ground 6 inches deep, when suddenly another, quite deafening shriek tore right through my eardrum; I had been about to dig the spade into the earth by my feet, but now stopped. Bewildered, I searched through the leaves and debris on the ground, my fingers digging deep, safe in the confines of my black Marigold rubber gloves, which, in the heat of the day, had filled with sweat from my hands so my fingernails were paddling in pools forming at the fingertips of the gloves, but I could still see nothing. Then, just in time, right there by the toe of my boot, next to the blade of my spade and camouflaged by the leaves on the ground, was a third magpie chick. It squatted belligerently, peering up at me with magpie fury. I realised that I might have cut it in two had it not made a noise.

With cheery visions of rearing magpie twins, I took it back to the house and wrapped it up in the T-shirt nest with its sibling. It didn’t struggle. It reminded me of one of those plump, rounded toys that are weighted at the bottom; you can knock them over and they always swing up again, but they don’t possess the means to walk.

For a while I had happy thoughts of naming them Samson and Delilah and waving them off to freedom in tandem when old enough, but when I came back later to check on my two guests I found the first chick was dead. If only I could have found it before the cat and the fly eggs… if only I had a magic wand.

I fervently hoped that rinsing the fly eggs off the first bird had not contributed to its death, although when I remembered those fly eggs I really believed that I had no choice but to remove anything that might become a maggot. This thought didn’t stop me berating myself, however: should I not have bathed it? Should I not have cleaned all the fly eggs off it? Could I have got to it before the cat did? Was it too warm? Or not warm enough?

The second chick was leaning away from its sibling as if disgusted. The little corpse must have been getting chilly to cuddle up to. I extracted the dead chick and buried it next to its other sibling beneath the twisty cupressus, seething with frustration at not knowing what would have made the difference between its life and death. I should have kept it warmer; I should have toasted it in the bottom oven of the Rayburn. I should have tucked it into my shirt so that it felt as if it was being mothered. Perhaps then it would have had more of a chance. But of course, shock is the real killer. Shock, and cats.

In my early twenties, I took in unwanted cats—I loved those cats and ended up with thirteen of them before I managed to rehome them all. But they killed things, and after living in Australia in my thirties and seeing cats kill so many of the indigenous marsupials, I went right off cats altogether.

Now I was determined to try and save the third bird. I chose not to think about how people would judge me bringing up a bird held in such high disregard.

Magpie food became a preoccupation all afternoon; I worked my way through planting azaleas and denuding the garden of worm life, small slugs, and a couple of woodlice. Every so often I’d take a break to feed George. (Who could just as easily have been Georgina: the name moved from the dead bird to the survivor; I like to recycle.) He’d raise his head on a neck that looked a foot long in comparison to his tiny, squat body, and open his mouth with an ear-splitting screech when he wanted food.

In the process of answering George’s dietary calls, I discovered an interesting thing about worms: they genuinely didn’t want to die; they didn’t think that a bird’s gullet was a nice, moist hole to slip into, so they fought like hell to escape George’s eager beak, twisting and writhing as I tried to dangle them into his throat. It was as if they were all eyes and aware of impending doom.

It wasn’t long before I developed the knack of pushing the end of the worm down George’s throat with the tip of my finger, and quickly shoving the rest of it into his jaw, before the other end of the worm got a curling grip on the side of his beak and hauled itself out. I noticed the back of the magpie’s tongue had a sort of two-pronged ledge that pointed down into its throat, as if to deter anything living that might want to scramble out again.

If worms had only a single thought in their little nematode bodies, it was that they wanted to LIVE.

The really big worms (and I found a couple of whoppers about 5 inches long) were so strong that it was almost impossible to get their whole length into the bird before they forced his beak open to effect their escape. And they could move fast. I caught one fleeing from a high-sided bowl and slithering rapidly across the kitchen worktop. Perhaps it would have been better to chop them up, but whenever I accidentally cut them in half with a spade, it made me cringe terribly, as if I expected to feel the cut myself. And they wriggled in apparent agony—not that being digested alive in a bird’s belly is any more pleasant. In any case, George seemed to have no trouble accommodating any size of worm, so chopping up worms was, I reasoned, thankfully unnecessary.

George’s temporary accommodation became the bundled T-shirt at the bottom of the dogs’ small wire-mesh carry-cage, placed on the floor by the Rayburn in the kitchen.

The kitchen was the only room in the huge house that actually had any space; all the other rooms were filled with stacked furniture, boxes of possessions that hadn’t been unpacked because there was nowhere to put the contents, bags of cushions and curtains and clothes, and then all the glass and crystal chandeliers I’d constructed from bits bought in a chandelier breaker’s. (This was a warehouse that contained nothing but the broken-up parts of chandeliers of all descriptions: long, dangling spiky crystals; pear-drop crystals; chains of crystals; boxes of new bead crystals; the wire pins used to curl through the holes in crystals to fix them to their base; green, red, yellow and orange glass ball pendants; glass arms; chandelier skeletons to adorn… these items and many, many more were heaped in boxes on rows of trestle tables, through which I would rummage for hours at a time during the two years I’d been house-hunting.)

Green plastic units inherited from the previous owners—some glazed, and mostly propped up on top of each other as opposed to being fitted—filled the kitchen. The aged dark green Rayburn slogged along in an effort to be warm but went cold every time I put something in it to cook, and the oven was a crock. The bare dark oak floorboards dated back to the Victorian rear part of the house, although the kitchen was in the Georgian front part. Everything was in a permanent state of “being unfinished,” which, for someone like me who likes to make order out of chaos, was a form of torture.

I could never get it properly clean or tidy because of all the rubble, boxes and bags; I felt demoralised by years of “camping out” in our own home, which is what we’d done for five years in the London house until it, too, was done. (It took another two years to sell.) But this house was going to take very much longer, and in the meantime, the seemingly never-ending state of the house made it so much easier for me to remain in the garden, where I was not constantly reminded of what a depressing shit-heap the inside of my home was. In the garden I could make a visible difference daily because the work necessary was something I was capable of, and didn’t require the costly employment of others; the electrician and plumber were slowly working their way through rewiring and plumbing indoors. When they finished, the house would already have cost much more than I would ever realise if I sold it again. In overcapitalising, I was confirming my intention of staying rooted to the little plot the house stood on. In constructing the garden, I was making it very difficult to sell in any case; after all, who would want to take on the work required for the upkeep?

Never before had I cared for a bird so young, so I was fascinated when George demonstrated that he was nest-trained and shoved his bottom over the side of the T-shirt I’d folded to put him on, in order to expel crap from his living area. Unfortunately, there was no height to allow for the clearance of bird crap, so it dribbled off the edges. His parents didn’t teach him to do this; it was wired into his brain, just as the colour of his feathers and the size of his beak were determined by his DNA.

The parents of some birds will wait for the faecal sac produced by their babies, grab it in their beaks and fly off to drop it like a miniature missile somewhere else. Sometimes they will eat it, supposedly because the matter still contains useful nutrients. George did not expel his poop in a faecal sac, so I could be certain that magpie projectile-pooing was now going to be a regular feature of my kitchen landscape.

If that was the case, George was going to need a more efficient nest to allow him better access to an edge over which he could dangle his posterior. In a forgotten corner of a kitchen cupboard I discovered a shocking-pink plastic salad bowl with a lime-green interior; for the price of £1 it had seemed like bright and happy value, although I’d never used it for anything. I filled the bowl with screwed-up newspaper, then arranged the T-shirt into a sort of nest shape on top.

Now George was raised off the newspaper-covered floor of the dog cage and could properly crap over the side of his nest. Although he could wobble and rock, he was unable to walk, so he remained squatting, gazing at the dogs outside the bars until he was hungry. Then he opened his mouth again, so that the top of his head looked about to flip off, and let out another of his blood-curdling shrieks: “FEED ME!” The only time he moved was to shuffle his backside to the edge of his nest.

I worked outside until around ten that evening, when it was too dark to see, and fed the bird a couple more worms that I’d saved. Then, as soon as the very last glimmer of light outside vanished, it was as if someone had switched him off; George’s neck retracted, his eyes shut, his body fluffed into an untidy ball of plastic-looking feather-sticks, and he was instantly asleep. He could have been a toy in which the battery had suddenly run out of juice.

Now I had a chance to examine him more closely; his rudimentary flying feathers were still contained in what looked like black plastic tubes that were breaking away at the ends, allowing the feathers inside to fluff out and give the bird a more appealing appearance. His underbelly was bald, and his papery pink skin allowed a clear view of the intestine that curled from his neck to his rear end. He wasn’t remotely beautiful, but he was certainly interesting.

I hoped he’d be alive in the morning.

Sunday 20 May

When I opened the kitchen door, George was chirping in a high-pitched rather pretty way; it was a sort of trilling sound and the dogs were delighted, padding around the cage beside the Rayburn and panting encouragingly at him. Widget, the runty Maltese terrier midget sister of Snickers, who was a slightly larger white mophead of a dog, watched the bird with devout interest as if she was watching a cooking programme on television; glance away and you won’t know how much tarragon to add to your frying chicken thighs in wine and crème fraiche, or whether you should use a bain-marie to cook the soufflé. Mouse, the old Maltese-cross, was largely uninterested and walked around him without acknowledgement. She was a princess and this thing in her living area was an untidy, smelly knot of strange bird-squeals.

Snickers, however, clearly wanted to adopt him. Wishfully, she paced the outside of the cage, while Widget stood watching her with an air of bafflement. She tried to lick George through the bars. I wondered if it was because he tasted interesting, or because she wanted to clean him as if he were her own, or if she would bite his head off were he more accessible.

George ate the rest of the worms that I’d glad-wrapped in a bowl with a tiny air hole last night to keep them fresh. The very, very big ones were obstinate again. Feeling dreadful as I dunked them in water (which also seemed to shock them into stillness) to make them more slippery to swallow, I then dangled their two ends into the back of George’s throat. One of the worms hooked the loop of its body over George’s beak as he tried to swallow both ends, so the more he swallowed the tighter the loop on his beak became: cartoonish. I unhooked the loop, stretching it over the tip of George’s eager beak so that he could swallow the worm.

He was gaining weight so rapidly, literally in front of my eyes, that the plastic bowl of his nest now rocked and tilted when he moved around in it. I weighted it with a couple of large stones in the bottom, so that when George stuck his backside over the edge, he didn’t topple the bowl over.

He also appeared to be more comfortable with the dogs and with me. I picked him up from time to time; he liked having his feet secured on my fingers as he nuzzled into my chest for support, because he couldn’t balance in my hand, he was too unsteady by far. OK, so he was cute, I thought, but he’s still a magpie with exploding dandruff.

As the hours passed, more and more of the plastic-looking black tubes containing new feathers, like super-thin straws with spiky ends, emerged from the small outgrowths—papillas—in his skin. They each began to fray at the ends, crumbling away to expose the soft feathers underneath, leaving heaps of grey dandruff at the bottom of his cage.

George was growing fluffier by the minute. Disconcertingly, I found that I wanted to be with him all the time, watching his almost visible development, feeding him until he couldn’t squeeze in another worm; I was transfixed, and felt that if I left the room for a moment I’d miss a whole other stage.

When George slept in between feedings he tried to tuck his head into his wing, but his feathers weren’t plentiful enough, his neck was too short, and his head was rather large and clumsy, so it didn’t work; he just appeared to be trying unsuccessfully to fold himself in half.

He was also, I must be honest, a little eating–shitting machine. “Don’t write the grotty stuff,” said a friend who was visiting during George’s adolescence when I mentioned my desire to record his existence. But why not? Birds crap, and baby birds crap enormous amounts because they eat vast quantities to fuel their prodigious growth rate, in some cases doubling in size every three days. My friend, I think, was quietly repelled by the proximity to a real live wild bird and its effluent, whereas all I saw was the most miraculous little creature doing what every creature does.

Vast quantities of projectile magpie poo were propelled sometimes out of the cage bars altogether, and on to the kitchen floor. On one occasion Snickers had a near miss when she was keeping vigil, facing his cage in a sphinx-like pose, head up, front paws forward, eyes, nose and ears alert when George shuffled to the edge of the makeshift nest in his colourful bowl, raised his tail feathers and aimed right at her; a shaft of flying magpie poo narrowly missed her right ear and hit the side of the kitchen unit behind.

My own wonderment at George was that he had blown in from the wild and, driven perhaps by a primal instinct to survive no matter what, had decided to let me take over his feeding and care. Adapt and survive, they say, and George was adapting—it was up to me to help him survive.

I tried not to worry about what would happen if George made it into adulthood; whether he would fly off, or whether I would have to accommodate him forever. I could only take one day at a time, especially as I didn’t want him to leave. When anyone asked what I was going to do with the bird, I told them that “the bird will decide,” which was true: it all depended on George, and I was going to have to accept his decision, even if I disagreed with it.

Monday 21 May

My days had come to follow a sort of pattern: bed late, then up before I’d had enough sleep. That way I felt as if I was somehow “making” extra time to get more done, while often feeling guilty that I was spending hours in the garden rather than on my next poetry book or painting.

Guilt is self-inflicted, and sometimes it is useful in driving us on to get things done—most of the time, however, it is pointless and painful. Guilt for me is what makes me get up in the morning to write and paint—or I will finish the day having added nothing to it: no little painting, no written word, no small effort that will go towards building a finished book, or an exhibition.

The unfortunate truth about my work is that it is all self-generated. No one is directing me; I am wholly responsible for succeeding or falling flat on my face. Ideas pop into my head and I have to decide if they are exciting enough to imbue me with the energy for their completion, in the hope that others will enjoy the results as much as I enjoyed the creating.

Working on poems for The Book of Mirrors, I was developing characters around “Stonepicker,” which was the title poem of an earlier collection, about a woman who harbours grievances against others in the belief that they are to blame for all that’s wrong in her life—she will never take responsibility for anything. I was creating a family for her: Stunckle, Stonepicker’s uncle, the man who believes everything is his right, and that he is elevated above all others; and Stunckle’s cousin, based on a self-appointed critic and arbiter of opinion who is so deeply insecure that he must bring others down in order to feel equal, which is one of my favourite wickedly brutal poems. The Book of Mirrors itself was my vision of a book that we open to see ourselves (or those we have met) as we (or they) really are—or could be.

All the experiences I’ve ever had with people who I’d like to avoid in future helped me to add flesh to my Stonepicker family.

Other life continued; renovations progressed slowly. In the early days we had an au pair, a Hungarian girl who wanted to improve her English, to help out around the house; she had no objection to a lack of children—I gave her the least awful bedroom while The Ex and I slept in a room with bare boards, pinned-up sheets as curtains, and the entire contents of my future linen cupboard in a heap of black bin bags piled in the corner.

But one night she came to find me to tell me her ceiling was making strange noises.

The ceiling creaked and groaned and spectacularly collapsed in front of me just as I opened her bedroom door, making a sandwich of the double bed. Clouds of dust billowed up from the debris, and, from the exposed rafters that were left behind, dead flies and crumbs of rubble continued to drop, like little afterthoughts, into the air cushion of plaster particles that swirled and eddied in an excited frenzy. I quickly shut the door on it; there was nothing that could be done, and the poor woman had to move to the only other available bedroom, which was full of light fittings. She lasted six months in Wales, and then either the renovations or the isolation from any interesting nightlife (or both) took its toll and she returned to London.

Friends came and went in a desultory fashion. I felt rather cut off; I’d enjoyed a hectic social life in London, although it would have crippled my efforts to work had I allowed it to. Here, I knew no one. But now I had other company; George was the new guest and I was besotted by what appeared to be his rapidly developing little bird-personality. This particular morning he was already the first thing on my mind, above even the dogs. I felt slightly guilty about that, but the dogs had food out all the time, so they could help themselves, and their water bowl was always full, whereas George couldn’t fend for himself in any way at all; he was helpless and needed me, and now my purpose was to keep him alive. The joy of such a purpose is that it gives you a reason to ignore everything else. There is nothing so effective in taking one’s mind off the practical concerns of our lives as a living creature that needs immediate care without which it will die, if we are so inclined to try and save it. And I was.

I was now living in my gardening clothes. The silk shirts I loved to wear when out and about in London hung limply in the wardrobe boxes, and I lived in men’s work trousers from a local shop, and tatty old T-shirts. I looked like a bag lady, permanently in green wellingtons or muddy trainers, and occasionally lipstick; blazing sun, howling wind and occasional sleet are very drying for the lips. I wore no other make-up. I felt very far removed from my old city life, when I wouldn’t go out of the door without a face full of warpaint.

Having always felt that small talk stultified my brain, and being rubbish at it, I was now spared an enormous number of conversations altogether, as my social life dwindled and calls to visit London almost vanished. Exciting London parties went on without me as I grew roots and flowered in the Welsh Marches.

My own conversation was limited to the names of plants that filled my head from morning until night; names that I can’t remember now, but which consumed me with desire back then. On this particular Monday I drove to the Derwen Garden Centre; there was a sale on. Even as I drove I could feel my heart rate increase with excitement at the idea of being able to buy multiple plants at bargain prices. I was uncomfortably aware that my addiction might seem odd to others. I was once addicted to cigarettes. Before I gave up on 8 March 1993, I smoked eighty cigarettes a day. Buying them had given me joy (in answering the need) and a sense of security (having enough for the next few hours), although getting down to one packet used to fill me with anxiety, because a single packet wouldn’t last me more than four hours at best, and that knowledge filled me with panic. Smoking had brought me a feeling of being “in the company of a friend,” albeit a friend who gave me a hacking cough, permanent phlegm and the breathlessness of a person three times my age.

Nicotine causes a constriction of the blood vessels; so, blessed with a normally very low blood pressure in any case, I now froze. I was cold everywhere and my feet and hands suffered terribly during winter gardening. I wondered if shrinking the blood vessels in my brain would contribute to dementia later and I increased my efforts to bin cigarettes forever. But I found it nigh on impossible.

When I did finally give up smoking, my skin appeared to plump up and soften, and I realised how cigarettes had dried me out. After years of trying and failing to kick the habit, I’d finally given up by repeatedly telling myself, “I’m not giving up, because I’VE NEVER SMOKED!” If giving something up was too difficult because it deprived me of a habit I enjoyed, then telling myself over and over “I’ve never smoked” meant that I wasn’t depriving myself of anything, and the withdrawal symptoms were aberrations that would pass. Which, after six months of weight gain (I put my head in the fridge and didn’t come up for air for three months), night terrors, muscle spasms and a phlegm-clearing cough, they did.

But now I had a new friend—George—and he wasn’t bad for my health in any way I could see, and his care could be neatly accommodated alongside my gardening obsession.

My father once told me what he described as a Chinese proverb, “Hair by hair you can pluck a tiger bald,” which was in the back of my mind as I faced the canvas painting hairs on to tigers, rabbits, cats, wolves, bears and chinchillas over the years. Every small effort contributed to a much larger picture—this belief, even before my father’s proverb, governed my life from childhood. I could see how starting something now, not next week, and sticking at it, would achieve goals as a result of my sheer doggedness if nothing else. In the back of my mind were all the projects, all the paintings and all the stories that I’d never finished, and “finishing everything” was going to be my new motto. I only hoped that the garden would be worthwhile; I had a suspicion that it was going to look a bit mad when completed. But better that than remaining a dream, like all the other gardens in my imagination over the years.

With a view to “finishing,” I did a bit more work on trying to dig up the ground elder in the flowerbed down the side of the house, but it was a thankless task; the smallest piece of root left would grow another healthy plant. I knew how indestructible it was, and the frustrating—and seemingly endless—effort of removing the ground elder demoralised me, because I knew it wasn’t worth planting anything in the soil afterwards. It was only a question of time before it returned again, having grown a whole new root system out of sight, before presenting itself afresh in all its vile greenery. The idea of clearing it over and over again at various points in the future simply added itself to a litany of other tedious but necessary tasks that I would have to keep repeating if I wanted to keep from being subsumed. I turned my thoughts to George instead, and found myself smiling.

There are always priorities in life, and often it is up to us to designate more importance to one responsibility or obligation above another. But when a living creature that cannot speak for itself enters the equation, it must come as a top priority by default. George’s sudden, unexpected presence in my life gave me the excuse to ignore everything that didn’t require immediate attention.

I noted today that George was quieter and less demanding. I’d run out of worms halfway through the day. (Have you any idea how exhausting it is to dig constantly for worms? It was just as hard a job for me as it would be for a parent bird.)

It seemed that I’d exhausted the worm-supply for the time being, or the worm-word had got out and they were sinking deeper into the ground for safety. (Only much later did it occur to me that I could have bought maggots and worms from a shop only 7 miles away that sells everything from chainsaws, horse nuts, goldfish and furniture to gardening supplies…)

So, now I was making little pellets out of minced beef when George screeched for food. Each time I would wet a pellet of the meat in a bowl of water so it slipped down more easily, and was less likely to stick to his beak. Usually after the first mouthful, he edged his bottom over the side of the nest and crapped; he was like a bird version of those plastic dolls that you give a toy bottle of real water to, that then pee on to your lap because you forgot it needs a nappy, because it is a DOLL.

As I child I had one once, but not for longer than it took me to dismember it; it was horribly life-sized, with batting eyelids when I tilted it one way or another. No one who really knew me would have given such a disgusting fake-human thing to me—I would much rather have had a train set.

Having disconnected the travesty of its rubbery limbs, I buried the evidence in the garden at the family home, Court Green in Devon, the house that was bought by my mother and father when they were very much still together in 1961, and where my brother, Nick, was born.

That doll revolted me; it was testament to the expectation that I would grow up to have a baby and be a mother; the weight of this expectation on me, just because I was a girl, was something I was conscious of even at the age of seven or eight, and I felt it was an imposition on what I regarded as my freedom of choice.

Many years later, when I was in my mid-teens, someone was digging a flowerbed at the family home when I heard a cry of horror. I ran to see what the matter was and found them holding up one of the doll’s arms, complete with hand; I suspect their first reaction had been to think it might be real, as it was life-sized. Plastic baby dolls apparently don’t compost.

Tuesday 22 May

George was more demanding today; I fed him little and often on worms and minced beef. He appeared to like being held, although if I picked him up I had to hook his feet over my fingers as he wasn’t very coordinated himself. He was beginning to develop quite a firm grip, although his toes felt soft against my skin; he wasn’t scratchy at all.

Everything I did, be it cooking a meal, or gardening, or working at the computer, or painting, I did with one eye on George.

I was having a look at a job that was being done by a local workman to patch the plaster on the walls and replace the windows in the living room on the middle floor when suddenly I heard Mouse barking from downstairs in a desperate warning fashion. She had a deep voice, that dog, for something that was so small, old, white and fluffy.

I raced towards her bark, Snickers and Widget skittering and slipping down the worn, dark oak Victorian stairs ahead of me. Mouse was still in her basket in the kitchen, and I glanced around frantically to see what was causing her to panic.

The first thing I did was check the dog cage for George. But although the doors of the cage were firmly fastened, George wasn’t there. For one awful moment I thought Mouse might have eaten him, then I remembered that Mouse had hardly any teeth; she’d still be chewing and there would be telltale feathers. She looked at me indignantly, raised to her full sitting height of barely 12 inches.

Then a plaintive squawk arose from the dogs’ food bowls in the corner of the kitchen floor by the sink, and there was George, clumsily perched on the edge of one of them, his tail propping him up in a rather lopsided fashion because one of his rudimentary wings drooped slightly, perhaps as a result of his fall from the family nest. It seemed that George had taken to self-service. I couldn’t understand how he’d escaped, as he appeared to be much too large to get between the cage bars.

Gently scooping him up, I placed him back on his T-shirt nest in the cage, but two minutes later all three dogs were barking; they had now tuned in to George and George’s actions directed them. So, my eyes were first on George. I watched, impressed, as he waddled to the edge of his makeshift nest on his heels, and fell over the side. Then, unsteady, he raised himself up, stumbled towards the bars like a drunk, turned sideways and slid one wing out of the cage. He squeezed his chest through, which must have hurt because he let out a cry of complaint, then the other wing followed. He was free. George, I discovered, was developing brains; this sideways crab-waddle seemed to me to be an extraordinary deduction for the little bird.

Magpies (Pica pica) have a brain-to-body mass ratio that is apparently only exceeded by humans. They can learn to imitate human speech, use tools, recognise people and remember who or what is dangerous and who or what is safe to be around. George’s deduction that, if he turned sideways, he could escape, meant that he’d thought about his size and shape in tandem with the narrow space available between bars. Most other birds—sparrows, pigeons, pheasants, chickens—would simply ram their heads through the opening and wonder why their bodies refused to follow. A buzzard or red-tailed kite might not think about the sideways waddle, but I can’t imagine that they would be so undignified as to try to cram themselves through a seemingly impossible gap.

Now George toppled forward in a heap on the floor outside the cage and tried to stand up. But he was too uncoordinated for this, so I picked him up and he snuggled into the crook of my arm. I gazed at his cage, racking my brain for a solution to his Houdini-like abilities, trying to judge the width of the bars against the size of his little breast; it would only be a couple of days until he was far too big to get through, so the solution only had to be temporary.

Then I had it! Cling film. I cling-filmed the sides of the cage including the main access door at the front. There was a door in the top of the cage that I could use instead.

But before I put him back, I thought George could do with some space to try out his new legs, so I set him on the kitchen floor for a bit. He was like a half-wound clockwork toy, reeling and stumbling this way and that, his wings out for support, tottering as if he were on vertiginous heels. The dogs followed his every move: Snickers licked George’s beak (presumably attracted by all that beef-mince flavour) and I let her, watching closely to make sure that she didn’t suddenly lunge forward and snap the little bird’s head off. She wouldn’t let Widget near George; she snarled at her smaller sister and Widget scampered away, only to come back for another look at the new plaything.

When he stretched, George’s legs were so long in comparison to his body they looked like stilts. He stumbled to a halt on his spiky little toes, shuffled his shoulder feathers so they ruffled, then raised himself unsteadily on his pins as if seeing how far they would go. Higher and higher he went, until he looked like a tiny black-and-white ball of wool on two very thin knitting needles. He peered down at the floor as if surprised to see it so far away.

When I put him back in his cage, he immediately tried to get out again; his new freedom had been snatched from him and he wasn’t having it; he bounced off the cling film over and over again until exhausted, and only then did he give up. He appeared to sulk like a child, squatting sullenly on the floor of his cage. I reached in from above and put him back in his bowl of a nest, turning the kitchen lights out so he’d sleep. I noted how he was quickly becoming a sort of magpie version of a belligerent teenager with attitude; I had visions of waking up in the morning to a magpie hoodie.

Because of George, rolls of paper kitchen towels would have to be a major purchase; they were the handy wipes for all the baby-bird excrement that escaped the confines of the cage. No bird-mother could have been more attentive than I was, and George’s screeches for attention dragged me from whatever I was doing; if he were to live, then he must be fed.

Wednesday 23 May

Further evidence was stacking up that life must, whether I liked it or not, return to a more work-focused ethic. It meant that I had to feed George only on bits of mince; there wasn’t time to find worms because I was working in the office on the following week’s poetry column for The Times all day, and it required dedication to go out and dig up the reluctant magpie snacks in enough quantity to satisfy George’s increasingly demanding appetite. How could he possibly eat so much?

And yet I found that I could not keep away from him; he was a little feathered magnet. Now and then I took him out to stroke him, having persuaded myself that I needed to make another cup of tea—and another—and another, so that I could justify deserting my computer.

George was totally trusting when I held him; he’d let me pick him up, put him down and move him around. The speed at which he was developing meant that a few hours made all the difference to his appearance and behaviour: it was amazing to see how his instinct for survival had easily allowed him to swap one black-and-white winged mother for a large, fleshy, beige-pink, fabric-covered one that was many times his own size, just as long as food was delivered on demand.

The dogs were now also fixated by George. When he was in his cage on the floor, they sat and waited outside it, napping when they weren’t watching him, but always keeping close.

On this particular afternoon I felt terribly tired—exhausted in fact, so much so that my efforts to work on my column were becoming counterproductive; I found myself sitting, dozing, and listing like a beached boat in my swivel office chair in front of the computer, unable to concentrate. I thought it might be a result of too much late-night work in the office, so I took a nap on the kitchen sofa. There is a protocol to this:

First, I fetch a blanket. The three dogs see what I am doing and line up in front of the sofa with expectant expressions on their little white faces, each punctuated by the three perfect black coals of eyes and nose. I stack a couple of cushions at each end to support my feet and my shoulders so that I’m in a nice, comfortable “V” shape, which is the only lying-down position that my arthritic disc-compromised back ever truly enjoys. At the time of writing this I have lost an inch and a half in height, which, when the doc measured me for some statistical requirement or other, shocked me as if I’d been punched.

Once I lie down with the blanket over me, doggy hierarchy is always imposed; Snickers is first up and tucks herself beneath my chin, as close to my face as she can manage without suffocating me. Widget is next, but, being shorter-legged than her sister, she uses a tiny footstool that I bought her for the purpose, to scramble on to the sofa in order to reach my lap, where she lies down next to Snickers. Then Mouse, as old as she is, scrabbles up the side of the heap; she tentatively uses the footstool, but only sometimes, because the dogs are all conscious that the stool is primarily for Widget. Only Widget will curl up on it and Snickers will never use it to access the sofa even if I attempt to persuade her. But she is able to jump up unaided in any case.

This afternoon, once the dogs were settled, I put George on my chest too, up against Snickers and on a T-shirt in case he felt the need to relieve himself. If I was taking time away from work in order to nap, spending time with all my animals simultaneously was a way of multitasking. Occasionally I’d open one eye and check on George; he was fast asleep as were the dogs. From time to time Snickers would lean over and lick George’s face, which really meant licking his beak. George tolerated it, visibly bracing himself against the pressure of her relatively large tongue against his tiny head. It was the closest thing to heaven (if a little weird) to lie there with three contented pooches and a napping magpie. I felt warm, loved and in good company. What they felt was presumably that they were a) near their food source, b) near a decent heat source, and c) they wouldn’t miss anything that might go on, since we were all there together in a big heap.

Thursday 24 May

Not missing out was important to George. Today I noticed that he never took his eyes off me; he didn’t miss a single action or movement that I made. I left him out for longer and longer periods of time, and he would just sit, observing me and the dogs, growing quietly, and shedding more and more dandruff from the sheaths of his feathers.

Stretching is a big thing with young birds; they test their legs and wings to the extreme, as if checking everything works for their maiden flight, since a second chance is often not an option if they crash and break their necks, or are found by a cat while semi-conscious.

George regularly tested his legs, rising up as if he were on pistons, then stretching his wings behind him and downwards; it was if he were breaking out of his physical restraints. If he could balance so he didn’t fall over, he’d look quite dignified, like a little man getting ready for a night out in his dinner jacket and white shirt, but usually he’d stumble and fall.

Most of the time he levered himself around, squatting on his heels, waddling like someone kneeling; he still couldn’t walk yet. What appeared to be his knees pointed backwards, but those were his heels, since his knees were really the bones up at the top of what appeared to be his thigh. I wondered if he had a birth defect when I noticed his ear openings were different heights and sizes.

Recently, in Bird Brain: An Exploration of Avian Intelligence by Dr. Nathan Emery, I found a mention that owls have one ear opening higher than the other in order to receive mismatched sound waves and so pinpoint prey. Although the ear holes of corvids aren’t mentioned, it describes George.

Six days after finding him the sheaths of George’s wing and tail feathers were almost all powdered off; he just had a couple of little bits left that Widget tried to nibble away. Dandruff was a daily feature of the kitchen floor; it gathered in heaps in the corners of the old, dark oak Victorian floorboards, and eddied and whirlpooled in the draught of opening and closing doors, prompting me to drag out the vacuum cleaner over and over again.

George seemed to enjoy affection, although maybe for him it was simply the need for food and warmth. But if he was out of the cage, he wanted to be close to me; my lap was his favourite place. This slowed me down terribly, as once he sat on my lap I was reluctant to move. But I had a sense that it wouldn’t be long before the chances to stroke this tiny magpie would evaporate as he developed independence.

Thinking I might never raise another magpie, I tried to keep a photographic record of me with this fascinating little bird, but it was hard to get a picture of us together, because I had to rely on the good nature of The Ex, who wasn’t the least bit interested. George, it seemed, was the competition.

Friday 25 May

For the first few days of his stay with me, I continued to see George as a magical creature. I was like any owner with a new pet: watching, worrying, fascinated as this little being did simple things, from his leg-stretching to his wing-arching. When he arched his wings, he’d bring them over his head like an angel, and he tried to clean his chest feathers, but his neck, while it stretched upwards, somehow wouldn’t let him reach his front.

Although he still screeched to be fed, he’d begun to peck occasionally at the meaty dog food that I kept topped up in dishes on the floor for the dogs, which was good, because it heralded the time when he could feed himself. Sometimes he managed to get a bit of dog meat in his beak and threw it back down his throat. I found it interesting that he developed increasingly adult habits so quickly and without any parent bird to copy. (Which was fortunate, as I was never going to demonstrate my dog-meat-eating skills for his benefit.)

Mostly, he liked company, and was very happy to sit on the table beside me, or on my lap. He was also happy just sitting in my hand as I moved around doing chores: cooking, tidying up, whatever I could do one-handed. Sometimes I held him in one hand while I painted with the other, and he’d watch my face, or my paintbrush as it moved, and seemed captivated. So was I. Of course, I realised that everything took twice as long to do with a magpie hanging off me, but I also wanted to make the most of every minute. His warmly feathered presence was like having an emissary of the natural world grounding me daily.

Today, George only fell off the kitchen table on to the floor twice. Gravity was his latest lesson. He did this a lot, as if trying to fly, but his little chin would hit the ground and he’d be in a heap. I don’t know if his fall was an intentional effort to see if he could fly or if it was just because he didn’t know what to do about the edge of the table. When I picked him up and put him on the crook of my arm, he climbed on to my shoulder and snuggled into my neck. I could feel his warm feathered body pressing against my skin.

Saturday 26 May

The Ex and I were invited out to have dinner with friends. It was the first time that I’d had to leave George at home for a whole evening. Going out to buy plants, or pots, or food for the house, I could rush back for the next feeding, but a whole dinner party would take hours. I found myself beset with anxiety for the bird: what if he suddenly got terribly hungry and I wasn’t there to feed him? What if he found out how to get part way—but not all the way—through the cling film that now swaddled the sides of his cage, and injured himself? What if he escaped and Snickers, in her excitement, ate him?

No sooner had we dressed for dinner, and left the house, than I wanted to turn around and come back home. Desperately, I thought up excuses: we had a flat tyre and the spare was missing or also flat; perhaps I’d developed an unexpected stomach bug and found myself throwing up in a lay-by. But if I did not accept invitations, I was never going to expand my almost non-existent circle of acquaintances.

All through the evening my mind was back at the house, imagining how George was. I smiled, I ate, I drank, I know I spoke to people but have no idea what I said. I hope I was a good guest; I felt warm and friendly towards the other guests, but also alien—they seemed so removed from reality for me. Inside my head I was hearing George making “feed me” noises. I made my honest excuses—I had to feed a baby magpie—and we left just slightly early, no doubt leaving behind us the impression of eccentricity.

When we got back, George was all curled up, perched on the edge of his nest, facing outwards rather than inwards; this was a new development. Snickers and Widget lay side by side in watchful attendance beside his cage, paws out in front of them, heads held high, necks taut, noses forward. I wondered if they’d moved at all since we left. George was doggy telly and they found him riveting.

As soon as he laid eyes on me, George gave a loud, demanding squawk, so I fed him another mouthful of minced beef and balanced him on my shoulder, where he stayed as I made a cup of tea. The practicalities of the makeshift kitchen meant that the teabags were a long way from the kettle, which was a long way from the cold tap, and the fridge was a satellite at the edge of the large room; the kitchen measured about 21 feet by 23 feet. As I moved about, I could feel George’s little toes gripping softly.

That night he curled up in his cage when I put him back, perching on the edge of the bowl instead of resting in the middle as he used to. Every day he was a little more aware, and since the sheaths of his feathers had pretty much gone now, he looked like a real magpie, only in chubby miniature. He was shabby, with bald patches on his head exposing his lopsided different-sized ear openings; his tatty appearance tugged at my heartstrings.

Sunday 27 May

As much as possible, I lived with George on my shoulder, his little claws digging in as he perched. For some reason he liked to face backwards when I walked. He’d crap on the arm of the work shirt I wore for the purpose, because he couldn’t lever his bum far enough over the edge of my shoulder. I cleaned it up. He was quite happy as I moved around the house, as long as I didn’t hurry; it unsettled his balance. The dogs played together on the floor and occasionally, when they came over to peer up at George, he let out a “feed me” screech as if he thought they could do just that. He talked to the dogs in a squeaky, chittery way, but they had no idea what he was saying. I’d never heard a bird make those sounds before. The chittering in adults is a really harsh sound, but this was gentle and almost musical. Sometimes it was as if he was asking a question.

He also made strange cackling, gurgling noises when he tried to communicate, which gave me the opportunity to shove minced beef down his throat every time he opened his beak; his screech was deafeningly loud in my ear… the piercing shard of his little cry would stab me right down to my cerebellum.

George’s appetite appeared to have increased suddenly, as if his metabolism had accelerated. In the previous week he’d already eaten countless worms, numerous slugs and almost an entire 1lb packet of minced beef.

Within days of taking up residence, George was trying to fly in earnest. This wasn’t just a falling-off-the-table effort, but a real attack on the process of becoming airborne. A week earlier, when he fell out of the bowl-nest, he couldn’t even stand up, but now he was demanding attention, regarding my shoulder as his very own perch, and was striding up and down the kitchen floor flapping his tatty wings, followed by Snickers who had definitely adopted him, and Widget, who wouldn’t let her sister have all the fun.

I wondered if I should pick George up and throw him into the air—after all, how else could I teach him to fly? But mother birds can’t teach their offspring to fly either; the babies have to get airborne on their own, and flying for birds is not always something that works first time.

First, there is the idea of owning wings: stretching, flapping, folding, the moment they have their first rudimentary feathers. The more developed their feathers, the more they are able to get an idea of the lift that flapping gives them. Then there is the distance between the nest and the ground below, which they will risk usually only when they are fully feathered, although the fluff may still be clinging on in places and their tails may be short and undeveloped.

Many common garden birds can’t fly right away and must spend a couple of days on the ground while their flight feathers grow that little bit more. Then their flight is necessarily unpredictable and badly executed. They might fly directly into an object instead of landing on it. They must practise, practise, practise.

Once they have flown the nest, they don’t return. The fledglings end up scurrying around the ground with their parents feeding them at intervals. Overnighting is the problem here; they have to find shelter and safety. But it is only a matter of a few short days before they are properly airborne.

One year I had three baby robins, three baby wrens and three baby blackbirds all arrive around my bird feeder during the same week. It was like having a kindergarten for feathereds. A window painter who was working for me at the time brought me two of the wrens, one after the other, thinking they needed help because it was possible to catch them, but they were perfectly healthy and very active; they just couldn’t get off the ground properly quite yet, although it would only be a day or two until they could.

The parents were always somewhere nearby, feeding them under my car, or on the bench near the bird feeder. There were plant pots and overgrown campanulas behind which they could scuttle and hide when they heard me coming. Most of the time they ignored me and just got on with the business of living, and I had the joy of watching them twitter and feed daily until the fledglings finally left altogether and the parents’ job was done.

Tuesday 29 May

Leaving the dogs and the magpie at home and making sure the magpie had food within reach should it be hungry, The Ex and I drove to London for the day for the first time in what seemed like an age. I didn’t want to go; I wanted to stay with George. However, he was old enough to feed himself if I left him with a bowl of dog food, and he wasn’t trying to escape his cage, so I was persuaded that the bird would be fine.

We got up early, packed a change of clothes and arrived at my Aunt Olwyn’s in Kentish Town about four hours later. Olwyn was in good spirits when we got there; I’d printed some photos of the evolving garden to show her, and she wanted to keep two or three of them, which was quite a compliment from someone so critical. Then, feeling rather excited at the idea of actually being able to dress up for the first time in many weeks, I changed into a smart, silky black trouser suit that hadn’t seen the light of day since I moved to Wales, and went off to meet my friend, a novelist and poetry anthologist, at the Wolseley. How surreal to go from mixing cement in trainers, combat trousers and skinny T-shirts, covered in drying mud, and wiping a magpie’s bum, to wearing an elegant outfit and 4-inch heels for tea at the Wolseley, followed by a party!

Looking around at the wind-tunnel faces, elegant manicures, expensive clothing and languid demeanour, I felt suddenly conscious of my dirt-ingrained fingernails (no amount of scrubbing could get them spotless) and my puppyish enthusiasm for everything from the other diners to the food. I was as curious as George was about every aspect of his new environment.

I managed to refrain from the boiling topic of magpie-rearing; it was difficult enough to resist talking about the garden, since that was the other main focus of my life at this point. Once or twice, when seeing friends, I’d mentioned that I mixed my own concrete and could see their eyes glaze over.

After changing at Olwyn’s into jeans and trainers, we drove back to Mid Wales in the middle of the night—all because of George, the miles stretching out before us until we reached the Welsh border and I felt a sudden wave of affection for my home. The dogs were delighted when we got back, and George, woken by the kitchen lights, was attentive and interested. He was still alive; that was the main thing.

Wednesday 30 May

The following morning, I got something of a surprise. Every day, without fail, the dogs lined up at the kitchen door so that, when I opened it, I was met by a row of three happy little faces, panting and eager for food and attention and a run in the garden. This time there was a row of the three dogs—and George at the end, wings out to support him, panting and happy and expectant just like the dogs. The four of them danced around my feet, giddy with excitement. I was astonished; the dogs had not eaten George. He didn’t even look slightly chewed around the edges, and as for George, he appeared to be imitating the dogs in every way, right down to the gallopy-prancing.

But I couldn’t work out how he’d escaped from his cling-filmed cage. On closer examination of the cage, the sides of which were still intact, I could see that George was, in fact, now too large to escape through the side bars, and I could remove the cling film if I wanted.

However, the bars in the top door of the cage, which I now used as access to get him out to play, alternated between narrow and wide. It seemed George had just discovered this too, and somehow squeezed through one of the wider gaps. But it would still have taken a magpie contortionist; how the hell did he get up? Even if he’d been able to fly, he’d have had to flap up (and wouldn’t be able to get through by doing that, as his wings would be in the way), then hang upside down from the bars by his feet, before hauling himself out. I just couldn’t see how his escape was possible; there were no conceivable means by which he could have got up and out between the wider-gapped bars without a ladder.

In hindsight, I wish I’d put George back in the cage and let him demonstrate his method, because once he’d found a way of doing something that worked, he’d do it again and again.

But I didn’t. Instead, I wrapped the top door in cling film too.

Often, I’d put George on the kitchen table, which was varnished, so it was very easy to clean. He’d hop about, examining me and pecking at objects: roses in a small vase, the salt and pepper, the gardening book, the newspapers; everything interested him and went into his beak to be picked at, dragged a bit, or dropped over the edge of the table on to the floor. He’d peer down after it as if questioning the fact that it existed at all, as it had now gone somewhere else.

When he tired of my shoulder, I kept a folded-up old T-shirt on the table at my elbow where George would sit, fluffing out his feathers, to watch me. His probable departure at some stage in the future was a thought that I pushed further and further to the back of my mind, but keeping him would be problematic; he had been a wild bird in the beginning, so shouldn’t he be a wild bird again? Though the knowledge that he could fly off and simply be shot was unbearable. The Ex was determined, however, that the bird should leave.

Time and again I told him that the bird would decide. I knew very well that I wanted the bird to stay with me; I longed to have George be a part of my daily life until one day in an unforeseeable future he dropped off his little perch from natural causes. I was astonished at the affection that I felt for this little black-and-white bundle after only twelve days.

While the dogs were a daily delight, having a wild bird adopt me was an inexplicable joy. At night, when I put out the kitchen light, with the dogs curled up in their baskets by the Rayburn, and George curled up in his bowl of T-shirt and newspaper in his cage on the floor next to them, I felt a real sense of peace. That little scene made me feel that everything was OK, and I could sleep, happy in the knowledge that my charges were a) still alive and b) apparently content.

After I’d had George for a couple of weeks, I found a bit of wood in the cellar, which I wedged between the bars of his cage so he had a proper perch. George liked his perch; he managed to hop up on to it from time to time. I might not have been a natural magpie-mother, but I was trying.

Reading Group Guide

Get a FREE ebook by joining our mailing list today! Plus, receive recommendations for your next Book Club read.

INTRODUCTION

When Frieda Hughes rescues a tiny magpie chick from a storm in her garden, she doesn’t expect him to last the night. But he does, and over the next weeks and months, Hughes watches George transform into a sharp, inquisitive creature as he learns to fly, feed himself, and roam the Welsh countryside, always returning at the sound of a whistle to land on her shoulder. Based on the journals she kept while George blossomed in her care—with the specter of his inevitable, permanent departure looming large—Hughes brings to life the bittersweet story of how it feels to unexpectedly love a wild thing who has chosen you for its home.

TOPICS & QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. If you had to describe George using just three adjectives, which would you choose? What moments in the book do you feel best encapsulate his personality? Do you have a favorite detail?

2. How do Hughes’s illustrations impact your reading? Which do you like best? Is there a scene in George that you wish had a visual?

3. Of George’s minor characters—both human and not—is there one you would have liked to learn more about? What interests you about them? How do they add to the narrative?

4. How would you describe the tone of George? What about Hughes’s sense of humor? Which moments do you find the funniest?

5. Compare and contrast how Hughes writes about George and The Ex. How does the way she describes her relationship with each of them mirror the other, especially in terms of the themes of freedom and letting go?

6. Hughes writes about a range of grief experiences in George. Are there any reflections that you find especially insightful? If you have faced similar loss in your life, do you find her depiction relatable?

7. In the first sentence of the prologue, Hughes writes, “Imagine wanting something since you were old enough to be conscious of wanting it” (1). George is in part about Hughes creating a life that she desires from the ground up—and how George was there with her on the journey. In this context, what do you think George represented to Hughes?

ENHANCE YOUR BOOK CLUB

1. As a group, come up with a list of books you’ve read that concern the relationship between animals and humans. Discuss how these selections differ from or are similar to the writing and structure in George. What is gained from Hughes’s approach? What about any films or other media that explore similar themes?

2. Pick a passage from George and write a paragraph or two from the magpie’s point of view. What sort of voice do you think the bird would have? What about Merlin, Eddie, Demelza, or Oscar?

3. Go back to the text and write down all the animals Hughes mentions, from the tabby cat and goat of her childhood to Wydffa and Arthur. How many can you count? Imagine a scene between Hughes and a supporting animal of your choice—how would you depict their relationship?

A CONVERSATION WITH FRIEDA HUGHES

George is based on diary entries you wrote as the events in the book were happening. What was the process of transforming those writings into the manuscript you submitted to publishers? How did you determine what was “useful information” that warranted later addition, as you write in “A Note on the Text”?

George went through many, many drafts!!! I began with the diary, then tried to get rid of as much of the repetition as I could, where George (or the dogs) did the same things over and over again. There was always the BIG question about how much of my life to put in the book, when, in my own mind, the book wasn’t supposed to be about my relatively mundane existence (impending marital separation notwithstanding) but George’s miraculous development. His burgeoning intelligence is what fascinated me, so I tried to keep mention of my life to a minimum, although it had to be in there to some degree to give a framework not only to George, but to me as George’s host. The question of, How much of my life is the right amount? caused me to rewrite several times, adding in, taking out. . . .

The “useful information” includes stories like those about the starlings and the gathering of crows. These events happened after George but were relevant in my mind to the behavior of birds and were so extraordinary in themselves that I felt they warranted inclusion. As were references to articles about corvids that were not available when I was rearing George. Being able to add extra information was the luxury of there being time between George’s arrival in my life and the publication of the book.

Has your relationship to privacy evolved over the course of your life? How, especially as it pertains to sharing your life in writing?

The short answer is YES, absolutely.

Curiously, just before reading this question I was working on a poem that is all about the way I would share everything with you if I knew that my secrets were safe with you, that you would never judge me, and that you would never use my personal information against me in any way—then I could tell you everything, if you were interested. But there will always be those who judge, and if I publish a secret then it’s no longer a secret. So, how much to share?

My life started so oddly when I was a child that I wanted to write it down and tell people, not just to share the oddity of it, but also to mark myself down as having truly existed, a sort of “I was here” literary version of graffiti.

As I grew into a teenager, my family circumstances demanded that I not tell people personal things because my family was inextricably entwined with me. It made me feel dumb, but I still wanted to be able to express myself. As a result, in my first collections of poetry, Wooroloo, Waxworks (especially Waxworks!), Stonepicker, and The Book of Mirrors, I used allegory where a family member or other third party might be involved; allegory became my first defense. But where a poem was only about me, I was blunt and up-front—poems, for instance, about surgery or my feelings about my mother.

In 45, my book of autobiographical poems published by HarperCollins in the United States, I distilled the first forty-five years of my life as I knew it into no more than three pages for each year. Each poem was accompanied by an abstract painting—a “Life Landscape”—that expressed my emotional reaction to the elements of each poem, although these were not included in the book. (To date, the paintings are still unseen and form a 225-foot-long, four-foot-high landscape of my life to the age of forty-five.) 45 was dipping my toe in the water of actual autobiography. And no one appeared to notice.

So, I grew bolder, and in Alternative Values, my abstract-illustrated book of poems published by Bloodaxe Books in the UK, I wrote poems about Love, Life, and Death, and I was open and frank and brutal. If it hurt, I described it; if it was glorious, I described that too. If I was angry that someone behaved a certain way, then I’d write it out. If I was puzzled or bemused, then that went in. Poems are where I work myself out in relation to my thoughts, experiences, and observations of others. My late father once observed that one cannot lie in a poem if the poem is to be any good, and I think he was absolutely right; it has to be authentic or it is a limp excuse of a poem. And so, as I have written one collection after another, I have tested the boundaries of what I am prepared to say.

But I am also getting older, and now it is a question of, What do I not want to be lost when I die, that other people might find useful? and What information would I like to leave behind to represent me? Also, Would anyone be interested? and Would anyone care?

The family who once might have been affected by much of what I’d write are all dead. That is both incredibly sad and literarily liberating.

Have animals affected your art?

Yes, along with birds, rocks, and trees. I do not love to paint human beings or anything man-made. I don’t find human beings attractive to paint although I enjoy sketching people and objects. I used to do portraits when I began as a painter, and never enjoyed it, but now I paint abstract “Life Landscapes” for people who tell me their life stories, where I record their highs and lows and the main events in their lives, in shape and color all over a canvas. (As I did with my own life when writing 45.) It becomes their own record of themselves in vibrant color! But when it comes to figurative work, animals—and anything from the natural world—win hands down every time. This stems from my very powerful affection for and feeling of connection with animals and birds and the joy they can bring.

Are there any books that you turned toward for inspiration as you were finalizing George?

Not particularly, although I read H Is for Hawk (published 2015) by Helen Macdonald, and Charlie Gilmour’s book Featherhood (published 2021), because it is interesting to see how other people deal with the bird- (or animal-) related memoir.

What is your favorite place in your garden?

Have you seen my garden? Almost anywhere! But mostly, the Bee House—a summer house with three glass walls and a golden bee as a weathervane on the pitch of the roof. It overlooks my lawn where my two rescue huskies play, and the massive flower beds that I planted with loving care, where my two rescue huskies trample stuff, and the house, in which there is so much to do that if I want to think straight it is better to be somewhere else.

Also, there is a slate-slab-floored, glass-sided balcony with a round slate table and slate stools in the top of a metal tree that I designed, that overlooks a courtyard flanked by my studios, with more flower beds and a raised fishpond. The dogs and I love to sit up there at sunset in summer, when the (real, live) ring-necked dove is nesting in the metal branches beneath, and all the clouds turn orange and the sky turns pink, and the birds sing their way into dusk.

How do you think about the relationship between independence and dependence in your life?

I think of independence and dependence in my life as being transactional. In my life I strive to be independent, but in being independent I then take on animals and birds that are entirely dependent on me, and I develop a relational dependence on them. Of course, any relationship is imagined on my part, and a result of my anthropomorphizing them.

What do you hope readers take away from George?

Joy, mostly. Also, the love of small, feathered things. And perhaps the curiosity to read my next book. George went on to have a happy ending in obtaining his freedom, having learned to look after himself in the wild. Had he not lived I don’t think I’d have written the book. The five months he spent with me were five of the most hysterical months of my life, and I’d be delighted if people enjoyed reading about him as much as I enjoyed living with him.

Product Details

- Publisher: Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster (June 18, 2024)

- Length: 288 pages

- ISBN13: 9781668016510

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“A poignant and funny memoir . . . George is a passionate book about unconditional love and commitment. It’s also fast-paced and suspenseful, full of amusing anecdotes, poems and Hughes’s sweet drawings of George.” —Nora Krug, The Washington Post