Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

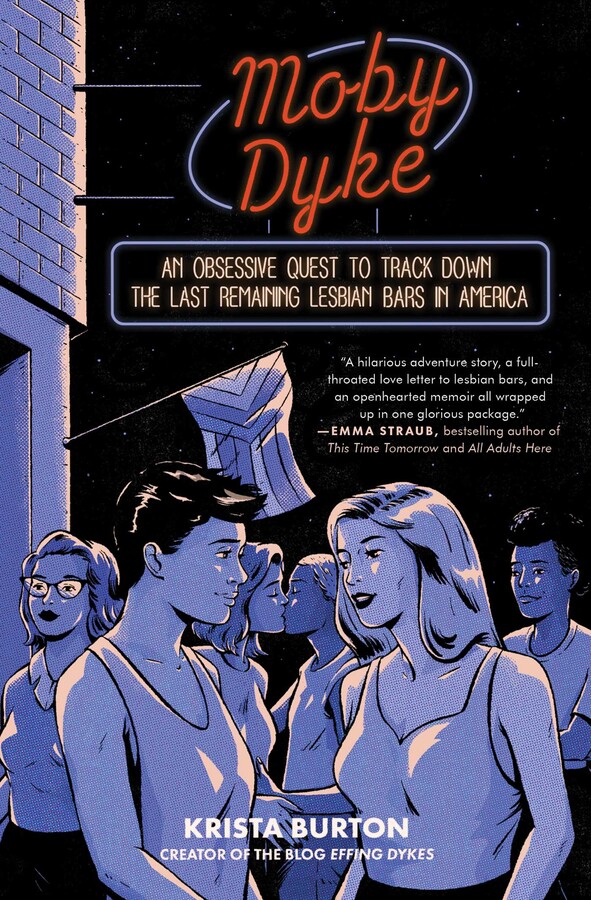

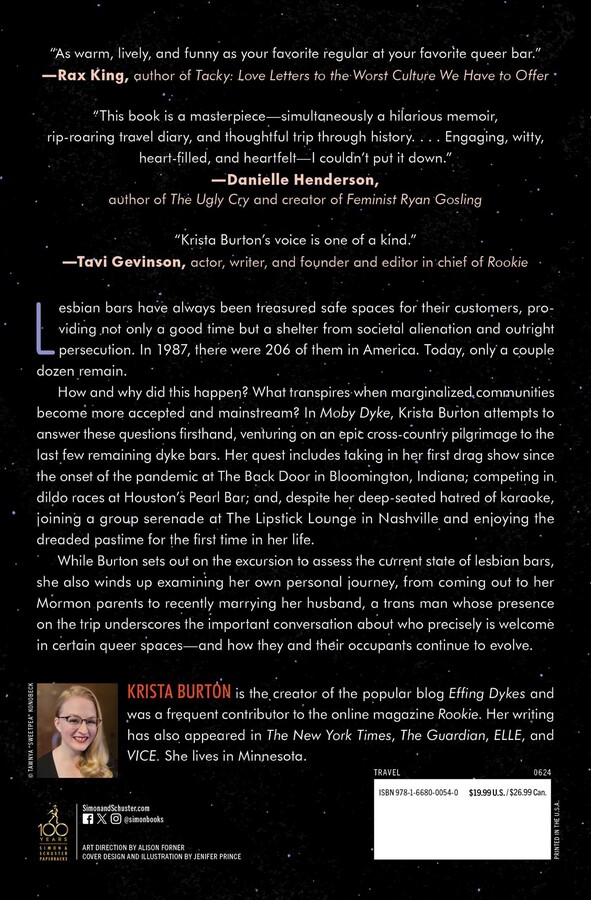

Moby Dyke

An Obsessive Quest To Track Down The Last Remaining Lesbian Bars In America

Table of Contents

About The Book

A former Rookie contributor and creator of the popular blog Effing Dykes investigates the disappearance of America’s lesbian bars by visiting the last few in existence.

Lesbian bars have always been treasured safe spaces for their customers, providing not only a good time but a shelter from societal alienation and outright persecution. In 1987, there were 206 of them in America. Today, only a couple dozen remain. How and why did this happen? What has been lost—or possibly gained—by such a decline? What transpires when marginalized communities become more accepted and mainstream?

In Moby Dyke, Krista Burton attempts to answer these questions firsthand, venturing on an epic cross-country pilgrimage to the last few remaining dyke bars. Her pilgrimage includes taking in her first drag show since the onset of the pandemic at The Back Door in Bloomington, Indiana; competing in dildo races at Houston’s Pearl Bar; and, despite her deep-seated hatred of karaoke, joining a group serenade at Nashville’s Lipstick Lounge and enjoying the dreaded pastime for the first time in her life. While Burton sets out on the excursion to assess the current state of lesbian bars, she also winds up examining her own personal journey, from coming out to her Mormon parents to recently marrying her husband, a trans man whose presence on the trip underscores the important conversation about who precisely is welcome in certain queer spaces—and how they and their occupants continue to evolve.

Moby Dyke is an insightful and hilarious travelogue that celebrates the kind of community that can only be found in windowless rooms soundtracked by Britney Spears-heavy playlists and illuminated by overhead holiday lights no matter the time of year.

Lesbian bars have always been treasured safe spaces for their customers, providing not only a good time but a shelter from societal alienation and outright persecution. In 1987, there were 206 of them in America. Today, only a couple dozen remain. How and why did this happen? What has been lost—or possibly gained—by such a decline? What transpires when marginalized communities become more accepted and mainstream?

In Moby Dyke, Krista Burton attempts to answer these questions firsthand, venturing on an epic cross-country pilgrimage to the last few remaining dyke bars. Her pilgrimage includes taking in her first drag show since the onset of the pandemic at The Back Door in Bloomington, Indiana; competing in dildo races at Houston’s Pearl Bar; and, despite her deep-seated hatred of karaoke, joining a group serenade at Nashville’s Lipstick Lounge and enjoying the dreaded pastime for the first time in her life. While Burton sets out on the excursion to assess the current state of lesbian bars, she also winds up examining her own personal journey, from coming out to her Mormon parents to recently marrying her husband, a trans man whose presence on the trip underscores the important conversation about who precisely is welcome in certain queer spaces—and how they and their occupants continue to evolve.

Moby Dyke is an insightful and hilarious travelogue that celebrates the kind of community that can only be found in windowless rooms soundtracked by Britney Spears-heavy playlists and illuminated by overhead holiday lights no matter the time of year.

Excerpt

1. San Francisco: Wild Side West San Francisco Wild Side West

Just because you can rent a scooter doesn’t mean you should rent a scooter.

I had been seeing them in the Mission all morning—electric blue mopeds zipping past, two young people giggling on them, the person on the back holding a frantically sloshing iced coffee in one hand.

“I think those are rentals,” I said, pointing at another one going by up the hill, this time ridden by twinks in matching checkered Vans slip-ons.

“No,” Davin said. “They can’t be.”

“I’m gonna look it up, maybe they’re not stupid expensive?”

We sat down on the steps of a pink-and-lavender house and checked on our phones. They were rental scooters, you could totally rent them; there was one parked right in front of us, and… wow, they were a lot cheaper than Uber or Lyft. Cheap was important; Davin and I were just coming off breakfast at Tartine (which is a famous bakery and which I’d of course never heard of, because I have a cold-shoulder dress I still think is kind of cute in the year of our lord 2023) and this bakery breakfast had been forty-three dollars!! For food you eat out of waxed paper!

Davin and I were quickly remembering that that’s how everything is in San Francisco: whatever it is, it’s just going to cost so much more than you think it will. After studying the glass case at Tartine, we’d ordered two croissants, one bite-size caramelized Bundt cake, one little tart with glossy lemon cream, and one small cold brew. At the register, Davin had been so startled by the price that he had coughed into his mask while handing over his credit card.

“Here you go,” he croaked at the barista, turning to bug his eyes at me. Forty-three dollars will buy you a ten-acre farm in Minnesota.

The barista passed me our cold brew over the counter. It was in a clear, biodegradable plastic cup, with a kind of mouth opening I had never seen before. It was like a sippy cup that you flipped back the top on. It felt incredible when you put your mouth on it to drink—so smooth, much better than a straw. It was what I imagine sucking on a dolphin’s dorsal fin would feel like. Davin and I were both impressed. We kept taking tiny sips as we walked, just to feel the mouth of the cup. “Ooh,” we said each time, smacking our lips. “Wow.”

And honestly? That’s one of the nicest things about having moved to the middle of nowhere. Everything in big cities impresses me so much now. It’s impossible to be jaded. In my real life, I live in a cornfield, but that weekend, I was standing on a busy street, holding cold brew trapped in a container designed to melt into the earth. We were decades behind this shit at home!

I don’t really live in a cornfield. I just live surrounded by them. Northfield, Minnesota, where Davin and I now live, is a town of twenty thousand people that’s forty-five minutes south of Minneapolis and St. Paul. It’s home to the headquarters of Malt-O-Meal, the makers of those giant bags of off-brand cereal you see piled in wire bins at the grocery store. You know—Toasty O’s instead of Cheerios; Marshmallow Mateys instead of Lucky Charms—knockoff cereal that tastes exactly like the name-brand kind but is half the price and comes in “body pillow size” instead of “family size.”

Northfield is also home to two private liberal colleges, Carleton and St. Olaf, which means that the town is a little progressive bubble encircled by Trump country for at least twenty miles in every direction. The colleges also mean that, for nine months of the year, there are slouches of spoiled teenage girls in ripped jeans perpetually standing in front of the register at my favorite coffee shop downtown. They all want a matcha latte with oat milk, even though there is clearly only one person making drinks and that shit needs to be hand-whisked for several minutes per drink. Sometimes the line backs out the door. Only the most unflappable baristas are scheduled for Saturday mornings.

Northfield’s motto is “Cows, Colleges, and Contentment,” and we live there because Davin tricked me. I didn’t know it, but he was playing a long game, years in the making. Davin grew up in both Northfield and Faribault, the next-nearest town, and when we both lived in Minneapolis and were dating, he used to take me to visit Northfield on the weekends. “Just to get out of town,” he’d say. “Have a little trip.”

Northfield is cute. Aggressively, in-your-face cute. It is the real-life version of Stars Hollow from Gilmore Girls. All the parking is free. All the buildings downtown are historic. Everything is walking distance from everything else, and nothing costs very much when you get to where you’re walking to. The Malt-O-Meal factory makes the air smell like Coco Roos (Coco Puffs) or Fruity Dyno-Bites (Fruity Pebbles), all of the time. I had never been to a town that looked like Northfield that was not devoted to cutesy twee tourism, but Northfield was dead serious. This was a real, working town, and as someone who had lived her entire adult life in big cities, I was fascinated. On our weekend visits, Davin would show me around, smiling a serene cult-member smile. This is the town square, he’d explain, gesturing to a tiny park with a working old-fashioned popcorn wagon staffed by cheerful, thick-suspendered senior citizens. This is the dam, where generations of families fish off the bridge. Here’s the café that looks and feels like 1995, down to the last detail (they just started taking credit cards!); there’s the impressive independent bookstore, stocked with the kind of books you’d never expect to find in a small town. Hey, did I know we could go tubing down Northfield’s river? Had I seen all the gay flags on people’s houses? Look, there’s another one!

I sensed what Davin was up to. I loved Northfield, but I wasn’t having any part of it.

“We are never moving here,” I’d warn him, licking a two-dollar maple ice cream cone and crunching my way through the red and yellow leaves drifting across the town square.

“OK.”

“I mean it. Never,” I’d insist, drinking an excellent eight-dollar cocktail at Loon Liquors, a distillery bizarrely located inside an industrial office park.

“Has anyone ever asked you to move here?”

“No,” I said, watching the light filter through green leaves swaying overhead in the Big Woods, a lush, waterfalled state park ten minutes from Northfield. “But we’re not going to.”

Four years after I first saw it, we moved to Northfield.

Davin has never once said “I told you so,” but I can tell he thinks it daily.

BREAKFAST AT TARTINE WAS ABSOLUTELY worth forty-three dollars (the lemon tart alone was), but Davin and I had arrived in San Francisco only the day before, and we’d already burned through the bulk of our budgeted funds for this trip.

So when we saw the cheap rental scooter, it looked like a good option for us. It would be a fun way to get around, and we could afford it.

All I had to do to rent it was watch a seven-minute video on my phone and take a quiz. And that was it: I was putting on the included helmet and trying to be OK with the fact that the inside of it smelled strangely sweet and fatty, like honey and dirty hair.

Now, I drive a scooter at home, so I was feeling confident, even if the streets of San Francisco are steep and crisscrossed with tram tracks that look like you shouldn’t drive on them. Straddling the scooter, I switched it on and turned to Davin.

“I’m going to take this around the block to make sure I feel comfortable before I have you hop on the back.”

He nodded, silent with admiration at how butch I was.

I twisted the scooter’s handle to give it some juice and crept up the street toward the Castro. Cars flowed behind me and around me. Careful, careful… oh, OK, this was easy.

A baby could drive this, I thought, revving the scooter up to its maximum 30 mph and cruising through a green light. This was great! The wind in your face, a cloudless blue sky, the perfect pastel houses terracing up and up! No more Ubers for us—we were scooter people, now!

At a red light, I looked left. And there it was: The steepest street I’d seen all morning. A street that was practically vertical.

I turned the scooter onto it.

“Let’s see what this thing can do,” I muttered under my breath, narrowing my eyes at the hill, suddenly the lesbian main character in a private The Fast and the Furious spin-off. I gunned the engine.

OK. Before we go any further, I need to explain that I’m clumsy. Not ha-ha-isn’t-that-cute-she’s-always-adorably-tripping clumsy. No. I am life-threateningly clumsy. Accident-prone, in a someone-call-an-ambulance kind of way. I have dislocated my shoulder falling out of a hammock. I have dislocated my shoulders three other unrelated times. I have broken my toes, my ribs, and both my arms twice. I have broken my nose by turning and hitting it against a doorframe. My tailbone is ruined from when I ran down a wooden staircase in new socks, slipped, and landed on my ass on the floor with my feet straight out in front of me. (Did you know your chiropractor can adjust your coccyx by sticking her fingers into your asshole? Did you know she can delicately suggest this procedure so that you’ll agree to it by calling it “an internal manipulation”? It’s true.) Two years ago, at a work dinner in an upscale San Antonio restaurant, I pulled a heavy bathroom stall door closed against my foot while wearing sandals, and my big toenail just popped off. It happened so quickly I didn’t even feel it; I looked down in confusion to see blood pouring down my sandal and pooling in a dark circle on the floor. My big toenail dangled by a thread of skin off to the side of my foot, like a press-on nail.

“Uh oh,” I said faintly. I made a split-second decision: I’d run at top speed back to my coworkers to get help. I’d be moving too fast to get blood on anything.

Friends, I sprayed that restaurant in blood. Ruby droplets flew through the air. Sandals clopping, a trail of gore spattering across white marble floors, I ran past tables full of startled couples about to tuck into plates of scallops. Across the restaurant, in slow motion, the hostess covered her mouth, watching.

What I’m saying is: I hurt myself constantly. Sensationally. I have no concept of my body in space. I had no business trying to see how well a scooter I’d never driven handled the steepest hill I’d ever seen.

And yet there I was, gunning the electric engine and murmuring “c’mon… c’monnnnn” as the bike began climbing the hill, already juddering with the effort. Ten seconds in, I knew it was a bad idea, but I’d already committed. I wanted to climb that hill. I wanted to not know what would happen. I’d wanted to do this lesbian bar road trip for four years, goddammit, and now I was getting the chance to do it, and I was going to say yes to new experiences, no matter how ill-advised they seemed. I was all in, twisting the scooter handle as hard as I could, eyeballing the distant summit of that hill. Let’s go.

Midway up, the scooter started slowing.

Dramatically.

My god. How was this hill even legal? I was basically parallel to the street, the scooter straining. I mean, the pedal was on the floor, and we were crawling, inching up the hill, the bike shaking like it was going to come apart.

No one was behind me. Houses passed at walking speed. A man with huge calves pushed his garbage out to the end of his driveway. I smiled and made eye contact, trying to make it look like I was OK and it was very normal to be seated on what felt like a small, rearing horse, trying not to topple backward at two miles per hour. He looked at me, expressionless, and walked back inside.

The scooter and I were nearly there. We were going to make it. And then—shuddering, gasping—the scooter crested the very top of the street. We’d done it!

Triumphant, I turned around to see how far up I was. San Francisco spread out beneath me like a dream city, the hills vanishing into hazy smoke from forest fires in the distance.

My god. What a view.

Overcome with relief, I relaxed my grip on the brakes.

The scooter started rolling backward.

“SHIT,” I whispered. I had two choices: roll backwards with the scooter and die, or flip the handlebars to the left as hard as I could, which would crash the bike.

I flipped the handlebars. The bike crashed to the ground and threw me off.

And somehow, twanged awake by the possibility of death on a mighty cement mountain, my body’s survival instincts took over. My arms wrapped themselves around me, my chin tucked into my chest, and I rolled over and over, partway down the hill. I was a log, tumbling. A log wearing cheetah-print overalls.

I popped up on my feet, breathing hard, fists clenched, adrenaline shooting through my body.

Nobody had seen me. There were no cars. No pedestrians. It was just me, alone near the summit of an empty, sunny, steep San Franciscan street lined with small stucco houses, whimpering “oh my god oh my god oh my god” and taking shaky breaths. I walked back up to the scooter, abandoned on its side in the middle of the street, mentally checking in on all my body parts.

OK. I’d scraped my foot. My left arm hurt. Gritting my teeth, I squeezed the length of my arm without looking at it, bracing myself to feel something new and unwelcome, like a bone poking out of my shoulder, or a pinky drooping at an odd angle.

No exposed bones. No free-range fingers.

I took a deep breath. There was no reason I should be unhurt, but I was. I picked up the fallen scooter (not a scratch on it!) and realized Davin was still waiting for me. I would have to drive to him. No way was I trying to go back down that hill, though, so, grabbing the scooter’s handlebars, I pushed it, slow and heavy, all the way back up to the top of the street, feet sweatily sliding in my sandals. I would drive around until I found a less steep hill to go down.

Ten minutes of circling later, I found an acceptably pitched hill and scooted back to Davin.

There he was, still standing on the corner.

“Where were you?”

I got off and told him what had happened. He gave me the kind of look you can only give your partner when you’ve spent years of your life filling out forms for them in the ER. He prodded me all over, poking suspiciously at joints and major bones.

“Do you think you could be bleeding anywhere inside? Like internal bleeding?”

“I don’t think so.”

Satisfied, he shook his head and climbed on the back of the scooter, wrapping his arms around my waist. “Let’s try to avoid hills, OK?”

WE WERE IN SAN FRANCISCO for one reason: to go to the very last lesbian bar in the city. Contrary to popular queer belief, there still is one. It’s just that nobody under fifty seems to know about it.

When I asked several Bay Area queers about San Francisco lesbian bars, they solemnly told me there weren’t any left—that the Lexington Club, which closed in 2015, was the last.

“The Lex closing still haunts me,” said my friend Shay, who’s lived in the Bay Area for fifteen years. “I get pangs in my chest when I pass by.”

“There aren’t any more lesbian bars in San Francisco,” said my friend Seven, who spent their twenties in Oakland and recently moved back there. “When the Lex closed, it broke my heart.”

It broke lots of sapphic-leaning hearts. Mine included. The Lexington Club was a divey dyke bar in the Mission. Founded in 1997 by Lila Thirkield, who later went on to found Virgil’s, a popular queer bar that closed in 2021, the Lexington Club was a landmark—a lesbian bar that never charged a cover, in the area surrounding Valencia Street. That part of town had attracted lesbians for decades, since it was close to the Castro, San Francisco’s gay district, but had cheaper rent. (And cheaper rent + gay-adjacent = lesbians. Always. Landlords, pay attention: This is the scientific formula for attracting lesbians, the greatest tenants of all time. Get yourself some lesbian tenants, and within weeks, that mud pit you advertise as a yard will be transformed into a bountiful garden. We’re talking raised beds, butterflies flitting, free tomatoes showing up in a bowl on your front porch, the whole thing. The shitty, splintered wood floors in your building will be refinished; every cracked wall you’re charging up the ass for will be spackled and painted a restful pale lavender. Want long-term tenants who make pickles and regularly go to bed at ten? Give some thought to lowering your rent slightly, dummies.)

The Lexington Club was the first real lesbian bar I ever set foot in. My first girlfriend, who I’d met while at college in Minneapolis, had moved to San Francisco for her job. I was twenty-one, newly out, completely in love with her, and selling my eggs to pay for my tuition and life. Flush with cash from my own ovaries, I would visit her in San Francisco regularly; sometimes twice a month. We would go to the Lexington Club. The first time I walked in there, I just—I couldn’t believe it. I had been to gay bars before in Minneapolis, but this was different. A whole bar, full of people like us? A whole bar full of people who probably also for sure liked women?!

On Friday and Saturday nights, the Lexington Club was always mobbed; there would be a large crowd of queers standing outside, smoking, making out against the walls in the dark, fishing their IDs out of their back pockets, fighting under the streetlight—either fully yelling or in that tense, whispery way that dykes in relationships fight when they’re out with their friends and one of them has just done something that needs to be Talked About Outside. You know: your basic talking laughing loving breathing fighting fucking crying drinking situation going on. Inside the Lex, there wouldn’t be space to move. The crush surrounding the bar was hopeless, three layers of people thick before you could come anywhere near the bartenders, who were unfairly cute and tattooed and would take your drink order with the indifferent expressions of the chronically hot and hit on.

A few years later, after my first girlfriend and I had broken up, I got a job taking the authors of educational books on weeklong seminar tours. I’d get sent to San Francisco often. I’d regularly end up at the Lex at night after work, powerless against the magnetic force that pulled me toward older butches with strong jawlines, muscled arms, and a wary look in their eyes. If none were available to stare hopefully at, I’d just sit in the bar, happy to be there and envious of the other queers surrounding me.

These gays live in San Francisco, I’d think, eyeing the shaved heads and piercings and complicated-rag outfits of the dykes walking through the front door. They’re not just tourists. They can come to the Lex whenever they want.

Even then, circa 2008–2010ish, San Francisco was so expensive that the only way most transplants could live in the city proper was to be either really rich or really broke (and thus OK with living in a shithole with seven other queers). No one I saw coming into the Lex looked remotely wealthy, though, and since most queers are not wealthy, in general, I knew the majority of the patrons had made a choice. They wanted to live in the gayest city in the world. Full stop. They were willing to be uncomfortable, to pay shocking rent, to live in busted, code-violating, closet-size rooms, just to be in the same vicinity as lots of other people like them. Just to have the Lexington Club be their neighborhood bar. Just to have access to a queer community, right outside their door. Even then, I knew I was unwilling to make a choice like that, and so I envied their commitment to the ~homosexual lifestyle~. I wanted a queer community, but I also wanted to remain unsure of what a bedbug looked like.

The Lexington Club was a legend; one of the last of its kind.

But not the very last.

The very last was right in front of me, at 424 Cortland Avenue in Bernal Heights. After parking the scooter, Davin and I walked up the hill from our Airbnb toward the wooden sign, which said:

THE WILD SIDE WEST

SINCE ’62

The Wild Side West is the oldest (and only) lesbian-founded, owned, and continuously operated lesbian bar in San Francisco. Opened in Oakland in 1962 by two out lesbians, Pat Ramseyer and Nancy White, the bar was originally just called the Wild Side, after the film Walk on the Wild Side, starring Jane Fonda and Barbara Stanwyck. Opening the bar was a wild act in itself—the San Francisco Bay Times reports that in California, in 1962, it was illegal for a woman to be a bartender, so two women owning their own bar? It was a big deal. A few years later, Pat and Nancy moved the Wild Side to San Francisco’s permissive, Beat-movement-famous North Beach neighborhood. They renamed it the Wild Side West. Sailors, artists, and musicians hung out in the bar. Janis Joplin is said to have played pool and music there.

But Davin and I were standing in front of the Wild Side West’s third and most permanent location, a tall, cream-colored, Victorian-looking house with purple trim. Pat and Nancy moved the Wild Side West to this Bernal Heights location in the late seventies; the bar’s been there ever since. Billie Hayes, the Wild Side West’s current owner, runs it now. (I’d tried calling the bar multiple times to see if I could get ahold of Billie, but no one had ever answered the phone.)

Looking around, I had a feeling that Pat and Nancy had bought property in Bernal Heights at the right time. The neighborhood had maybe gentrified just a tad since the seventies. Cortland Avenue was lined with bougie-looking restaurants and cafés stretching as far as I could see in both directions. Two doors down from the Wild Side West, a flower store’s windows displayed the kind of hand-selected, exotic-bloom, artisanal bouquets you only buy when you’ve really fucked up. Next door to the bar, a bicycle shop was selling $4,000 electric bikes.

Eeesh. Good thing Pat and Nancy had owned the property. The rent on a bar in this location in Bernal Heights now would be unthinkable.

I had never been to the Wild Side West before. I turned to Davin, nodding toward the bar’s facade. Wooden siding covered almost its entire front, where the windows should have been.

“Wonder what goes on in here,” I said, bouncing my eyebrows. I love bars without big front windows; they make me feel daring, like I’m about to step into a situation where privacy might be required. And this was San Francisco. A gay paradise! A city known for its tolerance and sexual diversity and leather bars! Maybe this bar was actually, like, a known place for anonymous public lesbian sex. Maybe we were about to walk into something like a gay bathhouse! Maybe no one under fifty had ever mentioned the Wild Side West to me because this bar was on the down-low in San Francisco—something you had to go looking for and discover for yourself!

Heart pounding, I pulled open the front door.

Oh. It was just a bar. No anonymous public lesbian sex happening, as far as I could tell.

But it was a strange bar. It looked… it looked kind of like a brothel? In a movie? It looked like an old western brothel, like Mae West was going to rustle around the corner in a corset and ruffled skirt any minute. It was fairly dark inside, but I could already see that the Wild Side West was, like so many dyke bars I’ve known and loved, painted dark red—walls and ceiling, everything. (Y’all, why is this a thing? Is it because red light is flattering on all skin tones? Is it a subtle, old-school nod to the mystery of the yoni? What is it with queers and blood-colored semigloss paint?)

A pool table dominated the front room. There were Pride flags and pennants for San Francisco sports teams everywhere; I saw a poster of Obama as a proud centaur, holding up an HRC logo and a pink triangle and wearing a rainbow tie on his top, human half. The walls were hung with porcelain masks and ornate mirrors and large paintings of women in various stages of draped, artistic nakedness. An old-fashioned barber chair sat near the front, the obvious king of all the mismatched chairs in the Wild Side West. A brick chimney ran up through the middle of the room, sharing space with a life-size, carved wooden figure of a Native American (yikes) standing next to it.

It felt dusty in there. It wasn’t that it looked dusty. It was just something you could feel in the faded hanging fabrics, in the old framed photos, the sheer amount of memorabilia in the space. This place had been lived in, and it had been loved, and it was old, now.

Davin and I headed for the wooden bar, where the bartender was polishing glasses and joking with a small knot of elder queers. We sat down. The bartender looked up at us. I held my breath. Here I was with Davin, a trans man with a beard, at the oldest lesbian bar in San Francisco. Would they be rude to him? Refuse to serve us? Throw him out?

The bartender’s eyes passed over us without seeming to register us.

“Vax cards and IDs, please,” they said.

Oh. Right! I loved San Francisco for this. You couldn’t step into a store or restaurant—you couldn’t even get a cup of coffee—without proving your vaccination status. It was such a relief, especially coming from Minnesota, where, just the week before, I’d seen a skinny teenaged Kwik Trip employee quaveringly ask a barrel-chested man at the store’s entrance to please wear a mask. Without breaking his stride, he’d said, “Make me,” and headed toward the bathrooms.

No one cared that Davin was there. No one seemed to even notice us, which was actually a little odd. I’d never been in a dyke bar, or any queer space at all, really, where people weren’t surreptitiously checking out who was walking in. Queers are fucking nosy—we have to look and see each other. But here, it was like we were ghosts. No one but the bartender had so much as glanced at us.

The door burst open, and three young, boisterously drunk queers stumbled in.

“It’s Emily’s BIRTHDAY!” one of them, a gangly gay in a crop top, crowed.

Emily grinned at the room, swaying gently. “My birthday,” she explained to us. “Today.”

The bartender didn’t blink. “Vax cards and IDs, please.”

“We want SHOTS!” one of them cried.

“BIRTHDAY SHOTS! For HER BIRTHDAY!”

“Vax cards.”

There was a tense pause. Then, suddenly meek, all three of them hunted through their pockets and produced their vaccination cards.

“Shots?” the gangly one asked.

“Let’s do it,” said the bartender.

There was an open door at the end of the bar, light spilling out of it. Another room, maybe? Davin and I walked through it.

And stepped out into a magical fairy wonderland.

You guys. Wild Side West has a garden. It’s not just a garden. It’s… this is the reason to go there. This garden is beautiful. And secretive. And green and dense and singing with crickets and twinkling with tiny sparkling lights, woven into falling-down trellises and around rotting wooden benches and heavy stone tables. The garden is so different from the inside of the Wild Side West that it’s bewildering—it’s a completely separate, hidden-away place.

This shock of a huge secret garden being where you do not expect a huge secret garden to be is one of the things I like best about San Francisco: it’s so full of surprises. It’s such a closed-off-to-the-street city; all the buildings are colorful, sure, but they have a hard look to them, with serious, twisting metal grates guarding their entrances. But then someone unlocks the grates and lets you in the front of a building and holy shit, here’s a sweet little courtyard with padded wicker chairs and flickering lanterns, and it’s all hidden from view on the street. Or maybe from the outside, the crumbling stucco on a house makes it look like an unlicensed vein removal clinic, but oh my god, look through the slots in the front fence and you can see an enclosed private terrace, overflowing with magnolia trees and bougainvillea. That’s how the Wild Side West is—the outside of it gives you no indication that the bar even has a garden, let alone that the garden will be enormous and glorious.

“Whoa,” Davin breathed, looking around.

The fully fenced-in garden sounded full of people, but because there were so many private areas to sit, it was hard to tell. Laughter floated into the night from unseen sources. People came down the patio steps, found their friends, and were swallowed whole into the foliage. We sat down at a table with a fraying rattan screen and wobbly wooden seats and took in the view. Lights wrapped around the trunks of trees. A headless mannequin stood creepily in a corner; faded plastic rocking horses guarded a flowering trellis. There were wrought iron chairs and statues and pots full of plantings, iridescent gazing balls, and succulents. A fountain trickled.

The garden is special partly because it feels so hidden, and partly because of how it got its start. When Pat and Nancy bought the place in the late seventies, neighbors welcomed them within days by throwing a broken toilet through the front window and dumping piles of household trash in front of the bar. They didn’t want a lesbian bar in their neighborhood. Pat and Nancy boarded up the front windows and picked up the trash. Early proponents of recycling, like all queers, they hauled the thrown objects down to the garden behind the house and used them to decorate. “Pat’s Magical Garden” is what the Wild Side West calls it. They literally made flowers grow from hatred and garbage.

To my right, partially shielded by the leaves of a huge monstera plant, two queers looked like they were on a first date that was going well. They were both dressed head-to-toe in black, and their hands were close but not touching across the top of their table. They were gazing into each other’s eyes, earnestly discussing their birth charts, and that’s so stereotypical I wish that I was making it up, but I’m not. While I watched out of the corner of my eye, one of them—the one wearing a big silver necklace—asked for the other’s Venus placement. Psssh. It was all over. They were gonna fuck tonight.

A group of what looked like young gay guys sat at a stone table, laughing and yelling and causing a ruckus. They were dressed to go out, and since it wasn’t super late, I guessed that Wild Side West wasn’t their final destination. One of them had a porn ’stache; they were wearing short-shorts and a baby blue satin jacket they were obviously proud of and kept smoothing.

A cluster of what looked like older lesbians was hanging out under a wooden shedlike structure near the patio, and they were causing the biggest ruckus of all. They sat in a semicircle, and it would be quiet for a second as someone spoke, and then they’d all break up, hooting and bellowing and slapping their legs. They had the appearance of having known each other for decades. It was clear they felt at home in this bar.

Watching them, I felt a pang of longing.

“We gotta get our shit together,” I said to Davin. He nodded. He’d been watching the older dykes, too, and knew what I meant. Someday, assuming climate change, nuclear war, or another plague doesn’t end the world as we know it within our lifetimes, Davin and I both want to live on a piece of land with all our queer friends. A bunch of little trailers, or maybe tiny cabins. It would be like a gay-ass summer camp that never ends, you know? “Beaver Gap,” we’ll call it.

But if you want to have queer friends you grow old with, you have to all agree on the place where you’ll do that, and none of us will commit to a location. We’re in Minnesota, Scotland, Chicago, Raleigh-Durham, New York, California… and we’re mostly settled. And while I appreciate the freedom to live anywhere we want, and I love visiting those places, I do feel a sharp sense of loss knowing I can’t see the people I consider my queer family on a daily basis. That is: I don’t want to see my loves once a year. I want to see them every day; enough to be sick of them. I want to rummage through their fridges, talk shit on their porches, tuck their plant cuttings into my pockets to bring home. I want them to let themselves into my house with their own keys; I want them to borrow so many of my books that my shelves look spaced and slanted, like a mouth full of crooked teeth. Watching the lesbians in the Wild Side West’s garden, gray-haired and laughing so hard they had to get thumped on the back—that’s it. That’s what I really want. That’s the goal.

But maybe they didn’t all live here. Maybe they were having a reunion. Or, if they did all live in San Francisco, who’s to say those older queers don’t envy what younger generations of queers have? Maybe they were all raised in San Francisco, and grew up in a time when there were far fewer options for meeting other lesbians. Maybe they’d lived in San Francisco by necessity, and were here because this community was what they had. And now this bar, the Wild Side West, was the last of its kind in the city, a last holdout as times changed.

I climbed up the patio steps to get two more bottles of Peroni, the only drink Davin and I could easily afford in San Francisco at this point. Inside, the birthday girl and her group had left. There were only two people at the bar, both elder queers. One of them, a butch with thick-rimmed black glasses and stylishly swooped silver hair, looked extra comfortable sitting there, almost proprietorial. Oh my god. Was this Billie, the owner??

I approached, hesitant.

“Excuse me, but… are you Billie?” I bleated. Jesus. I had to work on approaching strangers. This was embarrassing.

The older butch looked at me steadily for a second.

“No,” she said. “I’m Lisa.”

“Oh,” I said, dejected. “Because I’m writing about the last lesbian bars in the US, and I was hoping to talk to Billie about this place. I couldn’t get in touch with her.”

“Billie’s great. She’s not here right now. But this is a great bar. I’ve been coming to this place for—let me see—thirty-one years now,” said Lisa.

“Really?” I said eagerly.

“Yeah!”

“Would you mind if I asked you some questions?” I flipped open my notebook. “Starting with how you spell your name, and what your pronouns are?”I

A smile flickered across Lisa’s face. “I go by ‘she.’?”

She settled back in her chair. “This bar was different back in the day, of course—the bar scene and the bars were all different then. There were more of them, for one thing. Now there’s just this one.”

“Why do you think that is?” I asked. Oh my god. I was doing it! I was having a spontaneous conversation with a regular! “Why do you think lesbian bars are closing?”

Lisa took a sip of her drink. She looked thoughtful.

“Well… in my heart of hearts, I think it’s because we’re integrating into society; it’s way more acceptable now to be a lesbian,” she said. “I mean, there are a lot of reasons the bars are closing, from us earning seventy-nine cents to every dollar men make, to us fighting among ourselves about who can go to our bars. But honestly? I think it’s because we’re so adaptable.” She paused. “Yeah. We’re good at surviving. Our bars are closing because we don’t need them the way we used to. Society’s changing; we’re all changing. And I think that’s a very good thing.”

I blinked. What a cool answer. Especially from someone who could have, just as easily, been bitter or angry about the loss of lesbian spaces in San Francisco over the years. I thanked Lisa, and she waved me away, turning her attention back to her friend, who she’d been chatting with.

Conversation over, I pointed my camera way over the top of the friend’s head to take a picture of the art on the walls at Wild Side West. The friend looked at me, thinking I was taking a picture of her, and said, “Hey. Fuck you.”

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I wasn’t taking a picture of you. I was taking a picture of the bar.” I gestured to the masks along the wall.

“Fuck you,” the friend said again, pointing at me. Aggressive.

I looked at her uncertainly and took a few steps back. Was I about to get into a bar fight with a lesbian thirty years my senior?

“Hey now,” Lisa said.

“I’m kidding,” the friend said, spreading her hands open. “I’m kidding. I make jokes. That’s what I do.”

“Oh,” I said.

“I’m funny,” she continued. “That’s why I’m putting together a one-woman show.” She pointed at me again. “You should come. I made a whole show because I’m funny.”

“That sounds fun,” I said. “I’ll be right back.”

Beers in hand, I escaped to the patio. If I’ve learned anything as an adult, it’s that if someone feels the need to tell you something like “I’m funny” or “I’m really good in bed” or “I don’t believe in drama,” it’s because the opposite is true.

Down in the garden, Davin and I leaned into each other, sipping our beers quietly. A woman in a pretty red flowered dress came over and asked to use the ashtray at our table.

“Sure,” I said.

“D’ya mind if I sit?” she said, surprising me.

“No, of course! Sit down,” Davin said.

She sat down and sighed, tipping her chin up and away from us to exhale her smoke.

“I love this garden,” I said. “This is our first time here.”

“Oh really?” she said. “I’ve been coming here my whole life.”

“You have?”

“Oh, yeah. My whole life. I’ve always lived in this neighborhood,” she said. “I’ve been coming here since I was a little kid. My parents used to come here. Pat used to give me a soda at the end of the bar while I waited for them.”

“Wow,” I said. I explained what I was doing at the Wild Side West, and asked her if I could use her name.

“Not if it’s going in the book!” she laughed. “I hate being quoted. You can write down what I say, though.”

“Thank you,” I said, scribbling madly.

She nodded. “This is a community bar,” she said. “One of the best. I’ve never known another place like it. Did you know, this bar used to hold holiday parties for dogs? They’d play music and hand out treats to dog regulars during the holidays. Yeah. They do less of that stuff now. But dogs have always been welcome here. Everyone has. I’m not sure this bar should be on your list; it’s not really a lesbian bar. I mean, it is, but everyone’s welcome here. Neighborhood people come here. It’s way less ‘just lesbians,’ you know?”

“It feels that way.”

She took a final drag of her cigarette and stood up. “Well, it was nice talking to you both. You two have a nice night.”

She walked back up the garden path, toward the patio steps.

Davin and I looked around. The garden leaves rustled gently in the night breeze. The astrology queers next to us were comparing hand sizes. It was time to go.

We headed back inside, where someone was leading a scarred, muscled pit bull on a leash through the front door. The people who had trickled in and were sitting at the bar turned to her and cheered; she was clearly a friend of the bar, and a good girl, too—she sat down politely and thumped her tail against the floor while regulars gathered around to pet her.

As we left, I glanced back at the bar a final time. I could see why the Wild Side West was loved: it had survived so much, and it was so distinctive. I could also see why no one my age or younger had ever mentioned it to me: the inside of the bar felt a bit like a time capsule, a relic of what had already happened in queer history.

But that garden. Imagine living in the most famously gay city in the world and taking your crush to a garden like that. Imagine linking your fingers together while talking about your rising signs, completely hidden behind a giant potted fern, surrounded by magical gay trash.

The first bar of the trip had been a success. There were nineteen more lesbian bars to go. This was maybe going to be the best year of my life.

Davin and I walked toward our Airbnb, the evening air warm and smelling like a mixture of night-blooming jasmine and weed from the open windows of parked cars. The scooter we’d left in front of the apartment was still there, shining under the streetlights, a bucking blue bronco stabled for the night.

“Tomorrow, we can scoot all over,” Davin said.

I looked at him. “After what happened today?”

“You won’t crash it again.”

In the morning, we scooted all over San Francisco, the pavement glittering, the gulls wheeling overhead. On my own, I would never have rented another scooter again. Sometimes, though, all you need is someone warm at your back as you size up the next hill, yelling into your ear that you should go for it.

Just because you can rent a scooter doesn’t mean you should rent a scooter.

I had been seeing them in the Mission all morning—electric blue mopeds zipping past, two young people giggling on them, the person on the back holding a frantically sloshing iced coffee in one hand.

“I think those are rentals,” I said, pointing at another one going by up the hill, this time ridden by twinks in matching checkered Vans slip-ons.

“No,” Davin said. “They can’t be.”

“I’m gonna look it up, maybe they’re not stupid expensive?”

We sat down on the steps of a pink-and-lavender house and checked on our phones. They were rental scooters, you could totally rent them; there was one parked right in front of us, and… wow, they were a lot cheaper than Uber or Lyft. Cheap was important; Davin and I were just coming off breakfast at Tartine (which is a famous bakery and which I’d of course never heard of, because I have a cold-shoulder dress I still think is kind of cute in the year of our lord 2023) and this bakery breakfast had been forty-three dollars!! For food you eat out of waxed paper!

Davin and I were quickly remembering that that’s how everything is in San Francisco: whatever it is, it’s just going to cost so much more than you think it will. After studying the glass case at Tartine, we’d ordered two croissants, one bite-size caramelized Bundt cake, one little tart with glossy lemon cream, and one small cold brew. At the register, Davin had been so startled by the price that he had coughed into his mask while handing over his credit card.

“Here you go,” he croaked at the barista, turning to bug his eyes at me. Forty-three dollars will buy you a ten-acre farm in Minnesota.

The barista passed me our cold brew over the counter. It was in a clear, biodegradable plastic cup, with a kind of mouth opening I had never seen before. It was like a sippy cup that you flipped back the top on. It felt incredible when you put your mouth on it to drink—so smooth, much better than a straw. It was what I imagine sucking on a dolphin’s dorsal fin would feel like. Davin and I were both impressed. We kept taking tiny sips as we walked, just to feel the mouth of the cup. “Ooh,” we said each time, smacking our lips. “Wow.”

And honestly? That’s one of the nicest things about having moved to the middle of nowhere. Everything in big cities impresses me so much now. It’s impossible to be jaded. In my real life, I live in a cornfield, but that weekend, I was standing on a busy street, holding cold brew trapped in a container designed to melt into the earth. We were decades behind this shit at home!

I don’t really live in a cornfield. I just live surrounded by them. Northfield, Minnesota, where Davin and I now live, is a town of twenty thousand people that’s forty-five minutes south of Minneapolis and St. Paul. It’s home to the headquarters of Malt-O-Meal, the makers of those giant bags of off-brand cereal you see piled in wire bins at the grocery store. You know—Toasty O’s instead of Cheerios; Marshmallow Mateys instead of Lucky Charms—knockoff cereal that tastes exactly like the name-brand kind but is half the price and comes in “body pillow size” instead of “family size.”

Northfield is also home to two private liberal colleges, Carleton and St. Olaf, which means that the town is a little progressive bubble encircled by Trump country for at least twenty miles in every direction. The colleges also mean that, for nine months of the year, there are slouches of spoiled teenage girls in ripped jeans perpetually standing in front of the register at my favorite coffee shop downtown. They all want a matcha latte with oat milk, even though there is clearly only one person making drinks and that shit needs to be hand-whisked for several minutes per drink. Sometimes the line backs out the door. Only the most unflappable baristas are scheduled for Saturday mornings.

Northfield’s motto is “Cows, Colleges, and Contentment,” and we live there because Davin tricked me. I didn’t know it, but he was playing a long game, years in the making. Davin grew up in both Northfield and Faribault, the next-nearest town, and when we both lived in Minneapolis and were dating, he used to take me to visit Northfield on the weekends. “Just to get out of town,” he’d say. “Have a little trip.”

Northfield is cute. Aggressively, in-your-face cute. It is the real-life version of Stars Hollow from Gilmore Girls. All the parking is free. All the buildings downtown are historic. Everything is walking distance from everything else, and nothing costs very much when you get to where you’re walking to. The Malt-O-Meal factory makes the air smell like Coco Roos (Coco Puffs) or Fruity Dyno-Bites (Fruity Pebbles), all of the time. I had never been to a town that looked like Northfield that was not devoted to cutesy twee tourism, but Northfield was dead serious. This was a real, working town, and as someone who had lived her entire adult life in big cities, I was fascinated. On our weekend visits, Davin would show me around, smiling a serene cult-member smile. This is the town square, he’d explain, gesturing to a tiny park with a working old-fashioned popcorn wagon staffed by cheerful, thick-suspendered senior citizens. This is the dam, where generations of families fish off the bridge. Here’s the café that looks and feels like 1995, down to the last detail (they just started taking credit cards!); there’s the impressive independent bookstore, stocked with the kind of books you’d never expect to find in a small town. Hey, did I know we could go tubing down Northfield’s river? Had I seen all the gay flags on people’s houses? Look, there’s another one!

I sensed what Davin was up to. I loved Northfield, but I wasn’t having any part of it.

“We are never moving here,” I’d warn him, licking a two-dollar maple ice cream cone and crunching my way through the red and yellow leaves drifting across the town square.

“OK.”

“I mean it. Never,” I’d insist, drinking an excellent eight-dollar cocktail at Loon Liquors, a distillery bizarrely located inside an industrial office park.

“Has anyone ever asked you to move here?”

“No,” I said, watching the light filter through green leaves swaying overhead in the Big Woods, a lush, waterfalled state park ten minutes from Northfield. “But we’re not going to.”

Four years after I first saw it, we moved to Northfield.

Davin has never once said “I told you so,” but I can tell he thinks it daily.

BREAKFAST AT TARTINE WAS ABSOLUTELY worth forty-three dollars (the lemon tart alone was), but Davin and I had arrived in San Francisco only the day before, and we’d already burned through the bulk of our budgeted funds for this trip.

So when we saw the cheap rental scooter, it looked like a good option for us. It would be a fun way to get around, and we could afford it.

All I had to do to rent it was watch a seven-minute video on my phone and take a quiz. And that was it: I was putting on the included helmet and trying to be OK with the fact that the inside of it smelled strangely sweet and fatty, like honey and dirty hair.

Now, I drive a scooter at home, so I was feeling confident, even if the streets of San Francisco are steep and crisscrossed with tram tracks that look like you shouldn’t drive on them. Straddling the scooter, I switched it on and turned to Davin.

“I’m going to take this around the block to make sure I feel comfortable before I have you hop on the back.”

He nodded, silent with admiration at how butch I was.

I twisted the scooter’s handle to give it some juice and crept up the street toward the Castro. Cars flowed behind me and around me. Careful, careful… oh, OK, this was easy.

A baby could drive this, I thought, revving the scooter up to its maximum 30 mph and cruising through a green light. This was great! The wind in your face, a cloudless blue sky, the perfect pastel houses terracing up and up! No more Ubers for us—we were scooter people, now!

At a red light, I looked left. And there it was: The steepest street I’d seen all morning. A street that was practically vertical.

I turned the scooter onto it.

“Let’s see what this thing can do,” I muttered under my breath, narrowing my eyes at the hill, suddenly the lesbian main character in a private The Fast and the Furious spin-off. I gunned the engine.

OK. Before we go any further, I need to explain that I’m clumsy. Not ha-ha-isn’t-that-cute-she’s-always-adorably-tripping clumsy. No. I am life-threateningly clumsy. Accident-prone, in a someone-call-an-ambulance kind of way. I have dislocated my shoulder falling out of a hammock. I have dislocated my shoulders three other unrelated times. I have broken my toes, my ribs, and both my arms twice. I have broken my nose by turning and hitting it against a doorframe. My tailbone is ruined from when I ran down a wooden staircase in new socks, slipped, and landed on my ass on the floor with my feet straight out in front of me. (Did you know your chiropractor can adjust your coccyx by sticking her fingers into your asshole? Did you know she can delicately suggest this procedure so that you’ll agree to it by calling it “an internal manipulation”? It’s true.) Two years ago, at a work dinner in an upscale San Antonio restaurant, I pulled a heavy bathroom stall door closed against my foot while wearing sandals, and my big toenail just popped off. It happened so quickly I didn’t even feel it; I looked down in confusion to see blood pouring down my sandal and pooling in a dark circle on the floor. My big toenail dangled by a thread of skin off to the side of my foot, like a press-on nail.

“Uh oh,” I said faintly. I made a split-second decision: I’d run at top speed back to my coworkers to get help. I’d be moving too fast to get blood on anything.

Friends, I sprayed that restaurant in blood. Ruby droplets flew through the air. Sandals clopping, a trail of gore spattering across white marble floors, I ran past tables full of startled couples about to tuck into plates of scallops. Across the restaurant, in slow motion, the hostess covered her mouth, watching.

What I’m saying is: I hurt myself constantly. Sensationally. I have no concept of my body in space. I had no business trying to see how well a scooter I’d never driven handled the steepest hill I’d ever seen.

And yet there I was, gunning the electric engine and murmuring “c’mon… c’monnnnn” as the bike began climbing the hill, already juddering with the effort. Ten seconds in, I knew it was a bad idea, but I’d already committed. I wanted to climb that hill. I wanted to not know what would happen. I’d wanted to do this lesbian bar road trip for four years, goddammit, and now I was getting the chance to do it, and I was going to say yes to new experiences, no matter how ill-advised they seemed. I was all in, twisting the scooter handle as hard as I could, eyeballing the distant summit of that hill. Let’s go.

Midway up, the scooter started slowing.

Dramatically.

My god. How was this hill even legal? I was basically parallel to the street, the scooter straining. I mean, the pedal was on the floor, and we were crawling, inching up the hill, the bike shaking like it was going to come apart.

No one was behind me. Houses passed at walking speed. A man with huge calves pushed his garbage out to the end of his driveway. I smiled and made eye contact, trying to make it look like I was OK and it was very normal to be seated on what felt like a small, rearing horse, trying not to topple backward at two miles per hour. He looked at me, expressionless, and walked back inside.

The scooter and I were nearly there. We were going to make it. And then—shuddering, gasping—the scooter crested the very top of the street. We’d done it!

Triumphant, I turned around to see how far up I was. San Francisco spread out beneath me like a dream city, the hills vanishing into hazy smoke from forest fires in the distance.

My god. What a view.

Overcome with relief, I relaxed my grip on the brakes.

The scooter started rolling backward.

“SHIT,” I whispered. I had two choices: roll backwards with the scooter and die, or flip the handlebars to the left as hard as I could, which would crash the bike.

I flipped the handlebars. The bike crashed to the ground and threw me off.

And somehow, twanged awake by the possibility of death on a mighty cement mountain, my body’s survival instincts took over. My arms wrapped themselves around me, my chin tucked into my chest, and I rolled over and over, partway down the hill. I was a log, tumbling. A log wearing cheetah-print overalls.

I popped up on my feet, breathing hard, fists clenched, adrenaline shooting through my body.

Nobody had seen me. There were no cars. No pedestrians. It was just me, alone near the summit of an empty, sunny, steep San Franciscan street lined with small stucco houses, whimpering “oh my god oh my god oh my god” and taking shaky breaths. I walked back up to the scooter, abandoned on its side in the middle of the street, mentally checking in on all my body parts.

OK. I’d scraped my foot. My left arm hurt. Gritting my teeth, I squeezed the length of my arm without looking at it, bracing myself to feel something new and unwelcome, like a bone poking out of my shoulder, or a pinky drooping at an odd angle.

No exposed bones. No free-range fingers.

I took a deep breath. There was no reason I should be unhurt, but I was. I picked up the fallen scooter (not a scratch on it!) and realized Davin was still waiting for me. I would have to drive to him. No way was I trying to go back down that hill, though, so, grabbing the scooter’s handlebars, I pushed it, slow and heavy, all the way back up to the top of the street, feet sweatily sliding in my sandals. I would drive around until I found a less steep hill to go down.

Ten minutes of circling later, I found an acceptably pitched hill and scooted back to Davin.

There he was, still standing on the corner.

“Where were you?”

I got off and told him what had happened. He gave me the kind of look you can only give your partner when you’ve spent years of your life filling out forms for them in the ER. He prodded me all over, poking suspiciously at joints and major bones.

“Do you think you could be bleeding anywhere inside? Like internal bleeding?”

“I don’t think so.”

Satisfied, he shook his head and climbed on the back of the scooter, wrapping his arms around my waist. “Let’s try to avoid hills, OK?”

WE WERE IN SAN FRANCISCO for one reason: to go to the very last lesbian bar in the city. Contrary to popular queer belief, there still is one. It’s just that nobody under fifty seems to know about it.

When I asked several Bay Area queers about San Francisco lesbian bars, they solemnly told me there weren’t any left—that the Lexington Club, which closed in 2015, was the last.

“The Lex closing still haunts me,” said my friend Shay, who’s lived in the Bay Area for fifteen years. “I get pangs in my chest when I pass by.”

“There aren’t any more lesbian bars in San Francisco,” said my friend Seven, who spent their twenties in Oakland and recently moved back there. “When the Lex closed, it broke my heart.”

It broke lots of sapphic-leaning hearts. Mine included. The Lexington Club was a divey dyke bar in the Mission. Founded in 1997 by Lila Thirkield, who later went on to found Virgil’s, a popular queer bar that closed in 2021, the Lexington Club was a landmark—a lesbian bar that never charged a cover, in the area surrounding Valencia Street. That part of town had attracted lesbians for decades, since it was close to the Castro, San Francisco’s gay district, but had cheaper rent. (And cheaper rent + gay-adjacent = lesbians. Always. Landlords, pay attention: This is the scientific formula for attracting lesbians, the greatest tenants of all time. Get yourself some lesbian tenants, and within weeks, that mud pit you advertise as a yard will be transformed into a bountiful garden. We’re talking raised beds, butterflies flitting, free tomatoes showing up in a bowl on your front porch, the whole thing. The shitty, splintered wood floors in your building will be refinished; every cracked wall you’re charging up the ass for will be spackled and painted a restful pale lavender. Want long-term tenants who make pickles and regularly go to bed at ten? Give some thought to lowering your rent slightly, dummies.)

The Lexington Club was the first real lesbian bar I ever set foot in. My first girlfriend, who I’d met while at college in Minneapolis, had moved to San Francisco for her job. I was twenty-one, newly out, completely in love with her, and selling my eggs to pay for my tuition and life. Flush with cash from my own ovaries, I would visit her in San Francisco regularly; sometimes twice a month. We would go to the Lexington Club. The first time I walked in there, I just—I couldn’t believe it. I had been to gay bars before in Minneapolis, but this was different. A whole bar, full of people like us? A whole bar full of people who probably also for sure liked women?!

On Friday and Saturday nights, the Lexington Club was always mobbed; there would be a large crowd of queers standing outside, smoking, making out against the walls in the dark, fishing their IDs out of their back pockets, fighting under the streetlight—either fully yelling or in that tense, whispery way that dykes in relationships fight when they’re out with their friends and one of them has just done something that needs to be Talked About Outside. You know: your basic talking laughing loving breathing fighting fucking crying drinking situation going on. Inside the Lex, there wouldn’t be space to move. The crush surrounding the bar was hopeless, three layers of people thick before you could come anywhere near the bartenders, who were unfairly cute and tattooed and would take your drink order with the indifferent expressions of the chronically hot and hit on.

A few years later, after my first girlfriend and I had broken up, I got a job taking the authors of educational books on weeklong seminar tours. I’d get sent to San Francisco often. I’d regularly end up at the Lex at night after work, powerless against the magnetic force that pulled me toward older butches with strong jawlines, muscled arms, and a wary look in their eyes. If none were available to stare hopefully at, I’d just sit in the bar, happy to be there and envious of the other queers surrounding me.

These gays live in San Francisco, I’d think, eyeing the shaved heads and piercings and complicated-rag outfits of the dykes walking through the front door. They’re not just tourists. They can come to the Lex whenever they want.

Even then, circa 2008–2010ish, San Francisco was so expensive that the only way most transplants could live in the city proper was to be either really rich or really broke (and thus OK with living in a shithole with seven other queers). No one I saw coming into the Lex looked remotely wealthy, though, and since most queers are not wealthy, in general, I knew the majority of the patrons had made a choice. They wanted to live in the gayest city in the world. Full stop. They were willing to be uncomfortable, to pay shocking rent, to live in busted, code-violating, closet-size rooms, just to be in the same vicinity as lots of other people like them. Just to have the Lexington Club be their neighborhood bar. Just to have access to a queer community, right outside their door. Even then, I knew I was unwilling to make a choice like that, and so I envied their commitment to the ~homosexual lifestyle~. I wanted a queer community, but I also wanted to remain unsure of what a bedbug looked like.

The Lexington Club was a legend; one of the last of its kind.

But not the very last.

The very last was right in front of me, at 424 Cortland Avenue in Bernal Heights. After parking the scooter, Davin and I walked up the hill from our Airbnb toward the wooden sign, which said:

THE WILD SIDE WEST

SINCE ’62

The Wild Side West is the oldest (and only) lesbian-founded, owned, and continuously operated lesbian bar in San Francisco. Opened in Oakland in 1962 by two out lesbians, Pat Ramseyer and Nancy White, the bar was originally just called the Wild Side, after the film Walk on the Wild Side, starring Jane Fonda and Barbara Stanwyck. Opening the bar was a wild act in itself—the San Francisco Bay Times reports that in California, in 1962, it was illegal for a woman to be a bartender, so two women owning their own bar? It was a big deal. A few years later, Pat and Nancy moved the Wild Side to San Francisco’s permissive, Beat-movement-famous North Beach neighborhood. They renamed it the Wild Side West. Sailors, artists, and musicians hung out in the bar. Janis Joplin is said to have played pool and music there.

But Davin and I were standing in front of the Wild Side West’s third and most permanent location, a tall, cream-colored, Victorian-looking house with purple trim. Pat and Nancy moved the Wild Side West to this Bernal Heights location in the late seventies; the bar’s been there ever since. Billie Hayes, the Wild Side West’s current owner, runs it now. (I’d tried calling the bar multiple times to see if I could get ahold of Billie, but no one had ever answered the phone.)

Looking around, I had a feeling that Pat and Nancy had bought property in Bernal Heights at the right time. The neighborhood had maybe gentrified just a tad since the seventies. Cortland Avenue was lined with bougie-looking restaurants and cafés stretching as far as I could see in both directions. Two doors down from the Wild Side West, a flower store’s windows displayed the kind of hand-selected, exotic-bloom, artisanal bouquets you only buy when you’ve really fucked up. Next door to the bar, a bicycle shop was selling $4,000 electric bikes.

Eeesh. Good thing Pat and Nancy had owned the property. The rent on a bar in this location in Bernal Heights now would be unthinkable.

I had never been to the Wild Side West before. I turned to Davin, nodding toward the bar’s facade. Wooden siding covered almost its entire front, where the windows should have been.

“Wonder what goes on in here,” I said, bouncing my eyebrows. I love bars without big front windows; they make me feel daring, like I’m about to step into a situation where privacy might be required. And this was San Francisco. A gay paradise! A city known for its tolerance and sexual diversity and leather bars! Maybe this bar was actually, like, a known place for anonymous public lesbian sex. Maybe we were about to walk into something like a gay bathhouse! Maybe no one under fifty had ever mentioned the Wild Side West to me because this bar was on the down-low in San Francisco—something you had to go looking for and discover for yourself!

Heart pounding, I pulled open the front door.

Oh. It was just a bar. No anonymous public lesbian sex happening, as far as I could tell.

But it was a strange bar. It looked… it looked kind of like a brothel? In a movie? It looked like an old western brothel, like Mae West was going to rustle around the corner in a corset and ruffled skirt any minute. It was fairly dark inside, but I could already see that the Wild Side West was, like so many dyke bars I’ve known and loved, painted dark red—walls and ceiling, everything. (Y’all, why is this a thing? Is it because red light is flattering on all skin tones? Is it a subtle, old-school nod to the mystery of the yoni? What is it with queers and blood-colored semigloss paint?)

A pool table dominated the front room. There were Pride flags and pennants for San Francisco sports teams everywhere; I saw a poster of Obama as a proud centaur, holding up an HRC logo and a pink triangle and wearing a rainbow tie on his top, human half. The walls were hung with porcelain masks and ornate mirrors and large paintings of women in various stages of draped, artistic nakedness. An old-fashioned barber chair sat near the front, the obvious king of all the mismatched chairs in the Wild Side West. A brick chimney ran up through the middle of the room, sharing space with a life-size, carved wooden figure of a Native American (yikes) standing next to it.

It felt dusty in there. It wasn’t that it looked dusty. It was just something you could feel in the faded hanging fabrics, in the old framed photos, the sheer amount of memorabilia in the space. This place had been lived in, and it had been loved, and it was old, now.

Davin and I headed for the wooden bar, where the bartender was polishing glasses and joking with a small knot of elder queers. We sat down. The bartender looked up at us. I held my breath. Here I was with Davin, a trans man with a beard, at the oldest lesbian bar in San Francisco. Would they be rude to him? Refuse to serve us? Throw him out?

The bartender’s eyes passed over us without seeming to register us.

“Vax cards and IDs, please,” they said.

Oh. Right! I loved San Francisco for this. You couldn’t step into a store or restaurant—you couldn’t even get a cup of coffee—without proving your vaccination status. It was such a relief, especially coming from Minnesota, where, just the week before, I’d seen a skinny teenaged Kwik Trip employee quaveringly ask a barrel-chested man at the store’s entrance to please wear a mask. Without breaking his stride, he’d said, “Make me,” and headed toward the bathrooms.

No one cared that Davin was there. No one seemed to even notice us, which was actually a little odd. I’d never been in a dyke bar, or any queer space at all, really, where people weren’t surreptitiously checking out who was walking in. Queers are fucking nosy—we have to look and see each other. But here, it was like we were ghosts. No one but the bartender had so much as glanced at us.

The door burst open, and three young, boisterously drunk queers stumbled in.

“It’s Emily’s BIRTHDAY!” one of them, a gangly gay in a crop top, crowed.

Emily grinned at the room, swaying gently. “My birthday,” she explained to us. “Today.”

The bartender didn’t blink. “Vax cards and IDs, please.”

“We want SHOTS!” one of them cried.

“BIRTHDAY SHOTS! For HER BIRTHDAY!”

“Vax cards.”

There was a tense pause. Then, suddenly meek, all three of them hunted through their pockets and produced their vaccination cards.

“Shots?” the gangly one asked.

“Let’s do it,” said the bartender.

There was an open door at the end of the bar, light spilling out of it. Another room, maybe? Davin and I walked through it.

And stepped out into a magical fairy wonderland.

You guys. Wild Side West has a garden. It’s not just a garden. It’s… this is the reason to go there. This garden is beautiful. And secretive. And green and dense and singing with crickets and twinkling with tiny sparkling lights, woven into falling-down trellises and around rotting wooden benches and heavy stone tables. The garden is so different from the inside of the Wild Side West that it’s bewildering—it’s a completely separate, hidden-away place.

This shock of a huge secret garden being where you do not expect a huge secret garden to be is one of the things I like best about San Francisco: it’s so full of surprises. It’s such a closed-off-to-the-street city; all the buildings are colorful, sure, but they have a hard look to them, with serious, twisting metal grates guarding their entrances. But then someone unlocks the grates and lets you in the front of a building and holy shit, here’s a sweet little courtyard with padded wicker chairs and flickering lanterns, and it’s all hidden from view on the street. Or maybe from the outside, the crumbling stucco on a house makes it look like an unlicensed vein removal clinic, but oh my god, look through the slots in the front fence and you can see an enclosed private terrace, overflowing with magnolia trees and bougainvillea. That’s how the Wild Side West is—the outside of it gives you no indication that the bar even has a garden, let alone that the garden will be enormous and glorious.

“Whoa,” Davin breathed, looking around.

The fully fenced-in garden sounded full of people, but because there were so many private areas to sit, it was hard to tell. Laughter floated into the night from unseen sources. People came down the patio steps, found their friends, and were swallowed whole into the foliage. We sat down at a table with a fraying rattan screen and wobbly wooden seats and took in the view. Lights wrapped around the trunks of trees. A headless mannequin stood creepily in a corner; faded plastic rocking horses guarded a flowering trellis. There were wrought iron chairs and statues and pots full of plantings, iridescent gazing balls, and succulents. A fountain trickled.

The garden is special partly because it feels so hidden, and partly because of how it got its start. When Pat and Nancy bought the place in the late seventies, neighbors welcomed them within days by throwing a broken toilet through the front window and dumping piles of household trash in front of the bar. They didn’t want a lesbian bar in their neighborhood. Pat and Nancy boarded up the front windows and picked up the trash. Early proponents of recycling, like all queers, they hauled the thrown objects down to the garden behind the house and used them to decorate. “Pat’s Magical Garden” is what the Wild Side West calls it. They literally made flowers grow from hatred and garbage.

To my right, partially shielded by the leaves of a huge monstera plant, two queers looked like they were on a first date that was going well. They were both dressed head-to-toe in black, and their hands were close but not touching across the top of their table. They were gazing into each other’s eyes, earnestly discussing their birth charts, and that’s so stereotypical I wish that I was making it up, but I’m not. While I watched out of the corner of my eye, one of them—the one wearing a big silver necklace—asked for the other’s Venus placement. Psssh. It was all over. They were gonna fuck tonight.

A group of what looked like young gay guys sat at a stone table, laughing and yelling and causing a ruckus. They were dressed to go out, and since it wasn’t super late, I guessed that Wild Side West wasn’t their final destination. One of them had a porn ’stache; they were wearing short-shorts and a baby blue satin jacket they were obviously proud of and kept smoothing.

A cluster of what looked like older lesbians was hanging out under a wooden shedlike structure near the patio, and they were causing the biggest ruckus of all. They sat in a semicircle, and it would be quiet for a second as someone spoke, and then they’d all break up, hooting and bellowing and slapping their legs. They had the appearance of having known each other for decades. It was clear they felt at home in this bar.

Watching them, I felt a pang of longing.

“We gotta get our shit together,” I said to Davin. He nodded. He’d been watching the older dykes, too, and knew what I meant. Someday, assuming climate change, nuclear war, or another plague doesn’t end the world as we know it within our lifetimes, Davin and I both want to live on a piece of land with all our queer friends. A bunch of little trailers, or maybe tiny cabins. It would be like a gay-ass summer camp that never ends, you know? “Beaver Gap,” we’ll call it.

But if you want to have queer friends you grow old with, you have to all agree on the place where you’ll do that, and none of us will commit to a location. We’re in Minnesota, Scotland, Chicago, Raleigh-Durham, New York, California… and we’re mostly settled. And while I appreciate the freedom to live anywhere we want, and I love visiting those places, I do feel a sharp sense of loss knowing I can’t see the people I consider my queer family on a daily basis. That is: I don’t want to see my loves once a year. I want to see them every day; enough to be sick of them. I want to rummage through their fridges, talk shit on their porches, tuck their plant cuttings into my pockets to bring home. I want them to let themselves into my house with their own keys; I want them to borrow so many of my books that my shelves look spaced and slanted, like a mouth full of crooked teeth. Watching the lesbians in the Wild Side West’s garden, gray-haired and laughing so hard they had to get thumped on the back—that’s it. That’s what I really want. That’s the goal.

But maybe they didn’t all live here. Maybe they were having a reunion. Or, if they did all live in San Francisco, who’s to say those older queers don’t envy what younger generations of queers have? Maybe they were all raised in San Francisco, and grew up in a time when there were far fewer options for meeting other lesbians. Maybe they’d lived in San Francisco by necessity, and were here because this community was what they had. And now this bar, the Wild Side West, was the last of its kind in the city, a last holdout as times changed.

I climbed up the patio steps to get two more bottles of Peroni, the only drink Davin and I could easily afford in San Francisco at this point. Inside, the birthday girl and her group had left. There were only two people at the bar, both elder queers. One of them, a butch with thick-rimmed black glasses and stylishly swooped silver hair, looked extra comfortable sitting there, almost proprietorial. Oh my god. Was this Billie, the owner??

I approached, hesitant.

“Excuse me, but… are you Billie?” I bleated. Jesus. I had to work on approaching strangers. This was embarrassing.

The older butch looked at me steadily for a second.

“No,” she said. “I’m Lisa.”

“Oh,” I said, dejected. “Because I’m writing about the last lesbian bars in the US, and I was hoping to talk to Billie about this place. I couldn’t get in touch with her.”

“Billie’s great. She’s not here right now. But this is a great bar. I’ve been coming to this place for—let me see—thirty-one years now,” said Lisa.

“Really?” I said eagerly.

“Yeah!”

“Would you mind if I asked you some questions?” I flipped open my notebook. “Starting with how you spell your name, and what your pronouns are?”I

A smile flickered across Lisa’s face. “I go by ‘she.’?”

She settled back in her chair. “This bar was different back in the day, of course—the bar scene and the bars were all different then. There were more of them, for one thing. Now there’s just this one.”

“Why do you think that is?” I asked. Oh my god. I was doing it! I was having a spontaneous conversation with a regular! “Why do you think lesbian bars are closing?”

Lisa took a sip of her drink. She looked thoughtful.