Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

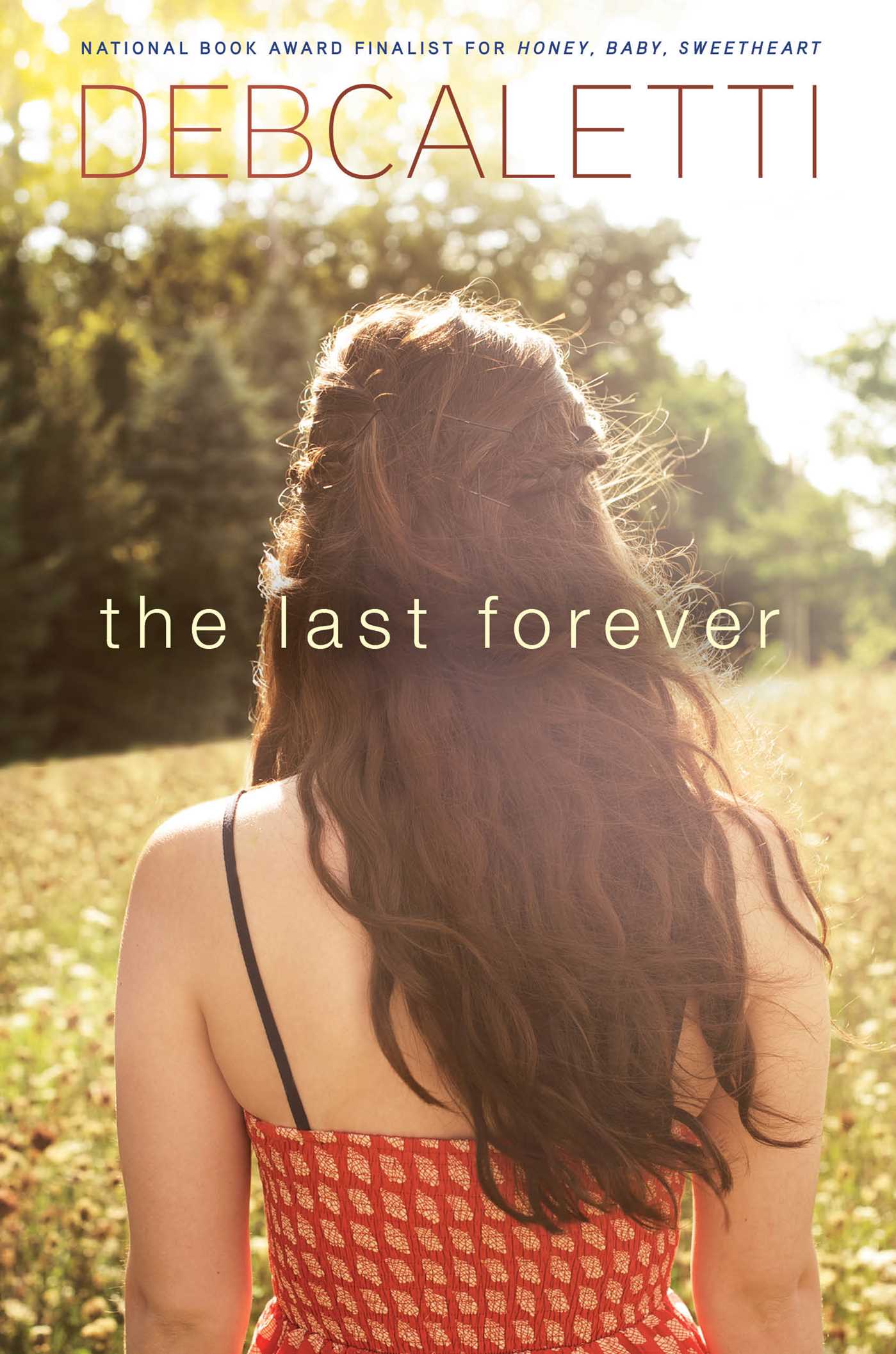

The Last Forever

By Deb Caletti

Table of Contents

About The Book

Beginnings and endings overlap in this soaring novel of love and grief from Printz Honor medal winner and National Book Award finalist Deb Caletti.

Nothing lasts forever, and no one gets that more than Tessa. After her mother died, it’s all Tessa can do to keep her friends, her boyfriend, and her happiness from slipping away. And then there’s her dad. He’s stuck in his own daze, and it’s so hard to feel like a family when their house no longer seems like a home.

Her father’s solution? An impromptu road trip that lands them in Tessa’s grandmother’s small coastal town. Despite all the warmth and beauty there, Tessa can’t help but feel even more lost.

Enter Henry Lark. He understands the relationships that matter. And more importantly, he understands her. A secret stands between them, but Tessa’s willing to do anything to bring them together—because Henry may just be her one chance at forever.

Nothing lasts forever, and no one gets that more than Tessa. After her mother died, it’s all Tessa can do to keep her friends, her boyfriend, and her happiness from slipping away. And then there’s her dad. He’s stuck in his own daze, and it’s so hard to feel like a family when their house no longer seems like a home.

Her father’s solution? An impromptu road trip that lands them in Tessa’s grandmother’s small coastal town. Despite all the warmth and beauty there, Tessa can’t help but feel even more lost.

Enter Henry Lark. He understands the relationships that matter. And more importantly, he understands her. A secret stands between them, but Tessa’s willing to do anything to bring them together—because Henry may just be her one chance at forever.

Excerpt

The Last Forever chapter one

Silene steophylla: narrow-leafed campion. Seeds from this delicate, white-flowered plant were found in a prehistoric rodent burrow in the Siberian permafrost. Scientists were able to successfully grow them, making these twenty-three-thousand-year-old seeds the oldest living ones ever discovered.

In those early months, when the beautiful and mysterious Henry Lark and I began to do all that reading, I often skimmed over the name. Svalbard. I’d see all those consonants shoved together and my brain would shut off. I thought it sounded like a Tolkien bad guy, or a word that might cast a spell. Here’s what I suggest—don’t even try to pronounce it. Just imagine it. I love to imagine it: a hidden building, a narrow wedge of black steel jutting from the ice. When I close my eyes, I see its long, rectangular windows—one on the roof, one at the entrance—a beacon of prisms glowing green in the deep twilight of the polar night. Fenced in and guarded, with steel airlock doors and motion detectors, it is the most protected place on earth. Outside, polar bears stomp and huff in the frigid air.

Or imagine this: that first monumental day of excavation, when the mayor of Longyearbyen, Kjell Mork, stood on the chosen spot with a fuse in his hand, ready to blast open the side of a frozen mountain. Longyearbyen, Kjell Mork—more Tolkien words, and Kjell Mork himself looks like a Tolkien king, with his snowy white hair and full blizzard of beard, the ceremonial chain of silver discs around his neck, representing his people and his place. Okay, he’s also wearing a blue hard hat and an orange construction vest, which would never work in the film version. But that fuse burning down, it would. He looks grim but determined in the pictures.

It all sounds like a fantasy novel, but it’s real. As I write this right now, as you read this, that place is there, tucked inside that mountain. As I pour my cereal or shove my books into my backpack, as you pay the cashier at the drive-through window or stare at the moon, it’s there. And it’s all—the guards, the buried chambers, the subzero temperatures—in service of the most simple, regular thing: a seed. Actually, a lot of seeds. Three million seeds. That’s what it’s for. To protect seeds in the event of a global catastrophe. To make sure that, even if there’s a nuclear war or an epidemic or a natural disaster, even if the cooling systems within Svalbard itself are destroyed, the seeds will survive for thousands upon thousands of years.

What should never be forgotten is this: Even when times are dark, the darkest, even when you are sure that life as you know it is over, there are still things that last. I learned that. Henry Lark and I both did. You may not be able to see those things. They may be hidden deep under the ground, or they may be tucked even deeper into your heart, but they are there.

And how did I, a regular person, as regular as those seeds themselves, become connected to a frozen vault 3,585.1 miles from home? (5,769.7 kilometers and seven hours and twenty-seven minutes away by plane, to be exact.) You never know what life will bring; you never do. It’s something my mother always said. In good times and in the worst times she said that, and she was right. We—that vault and me—we’re an unlikely pair. There is that land of wintry wildness and midnight sun and the eerie blue of polar nights and then there’s me, a person who chops her bangs and reads too much. But I am now forever connected to this most brave and defiant place.

How and why is what this story is about. Here to there. Here to there is where all the stories are. Here to there is the sometimes barren land you must cross to find the way to begin again.

Silene steophylla: narrow-leafed campion. Seeds from this delicate, white-flowered plant were found in a prehistoric rodent burrow in the Siberian permafrost. Scientists were able to successfully grow them, making these twenty-three-thousand-year-old seeds the oldest living ones ever discovered.

In those early months, when the beautiful and mysterious Henry Lark and I began to do all that reading, I often skimmed over the name. Svalbard. I’d see all those consonants shoved together and my brain would shut off. I thought it sounded like a Tolkien bad guy, or a word that might cast a spell. Here’s what I suggest—don’t even try to pronounce it. Just imagine it. I love to imagine it: a hidden building, a narrow wedge of black steel jutting from the ice. When I close my eyes, I see its long, rectangular windows—one on the roof, one at the entrance—a beacon of prisms glowing green in the deep twilight of the polar night. Fenced in and guarded, with steel airlock doors and motion detectors, it is the most protected place on earth. Outside, polar bears stomp and huff in the frigid air.

Or imagine this: that first monumental day of excavation, when the mayor of Longyearbyen, Kjell Mork, stood on the chosen spot with a fuse in his hand, ready to blast open the side of a frozen mountain. Longyearbyen, Kjell Mork—more Tolkien words, and Kjell Mork himself looks like a Tolkien king, with his snowy white hair and full blizzard of beard, the ceremonial chain of silver discs around his neck, representing his people and his place. Okay, he’s also wearing a blue hard hat and an orange construction vest, which would never work in the film version. But that fuse burning down, it would. He looks grim but determined in the pictures.

It all sounds like a fantasy novel, but it’s real. As I write this right now, as you read this, that place is there, tucked inside that mountain. As I pour my cereal or shove my books into my backpack, as you pay the cashier at the drive-through window or stare at the moon, it’s there. And it’s all—the guards, the buried chambers, the subzero temperatures—in service of the most simple, regular thing: a seed. Actually, a lot of seeds. Three million seeds. That’s what it’s for. To protect seeds in the event of a global catastrophe. To make sure that, even if there’s a nuclear war or an epidemic or a natural disaster, even if the cooling systems within Svalbard itself are destroyed, the seeds will survive for thousands upon thousands of years.

What should never be forgotten is this: Even when times are dark, the darkest, even when you are sure that life as you know it is over, there are still things that last. I learned that. Henry Lark and I both did. You may not be able to see those things. They may be hidden deep under the ground, or they may be tucked even deeper into your heart, but they are there.

And how did I, a regular person, as regular as those seeds themselves, become connected to a frozen vault 3,585.1 miles from home? (5,769.7 kilometers and seven hours and twenty-seven minutes away by plane, to be exact.) You never know what life will bring; you never do. It’s something my mother always said. In good times and in the worst times she said that, and she was right. We—that vault and me—we’re an unlikely pair. There is that land of wintry wildness and midnight sun and the eerie blue of polar nights and then there’s me, a person who chops her bangs and reads too much. But I am now forever connected to this most brave and defiant place.

How and why is what this story is about. Here to there. Here to there is where all the stories are. Here to there is the sometimes barren land you must cross to find the way to begin again.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atheneum Books for Young Readers (March 1, 2016)

- Length: 352 pages

- ISBN13: 9781442450028

- Grades: 7 - 7

- Ages: 12 - 99

- Lexile ® HL720L The Lexile reading levels have been certified by the Lexile developer, MetaMetrics®

Browse Related Books

Awards and Honors

- MSTA Reading Circle List

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Last Forever Trade Paperback 9781442450028

- Author Photo (jpg): Deb Caletti Photograph © Susan Doupé(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit